Why are so many people still dying from snake bites?

- Published

Tens of thousands of people die from snake bites worldwide every year. Lack of treatment and even the wrong medicine mean many of these deaths are preventable.

Snake bites may not strike you as being a major public health problem.

But in some parts of the world they are a daily risk, and can be lethal or life-changing.

Victims often do not get the treatment they need in time, if at all.

In other cases, they are given medicine to treat an injury caused by a different snake.

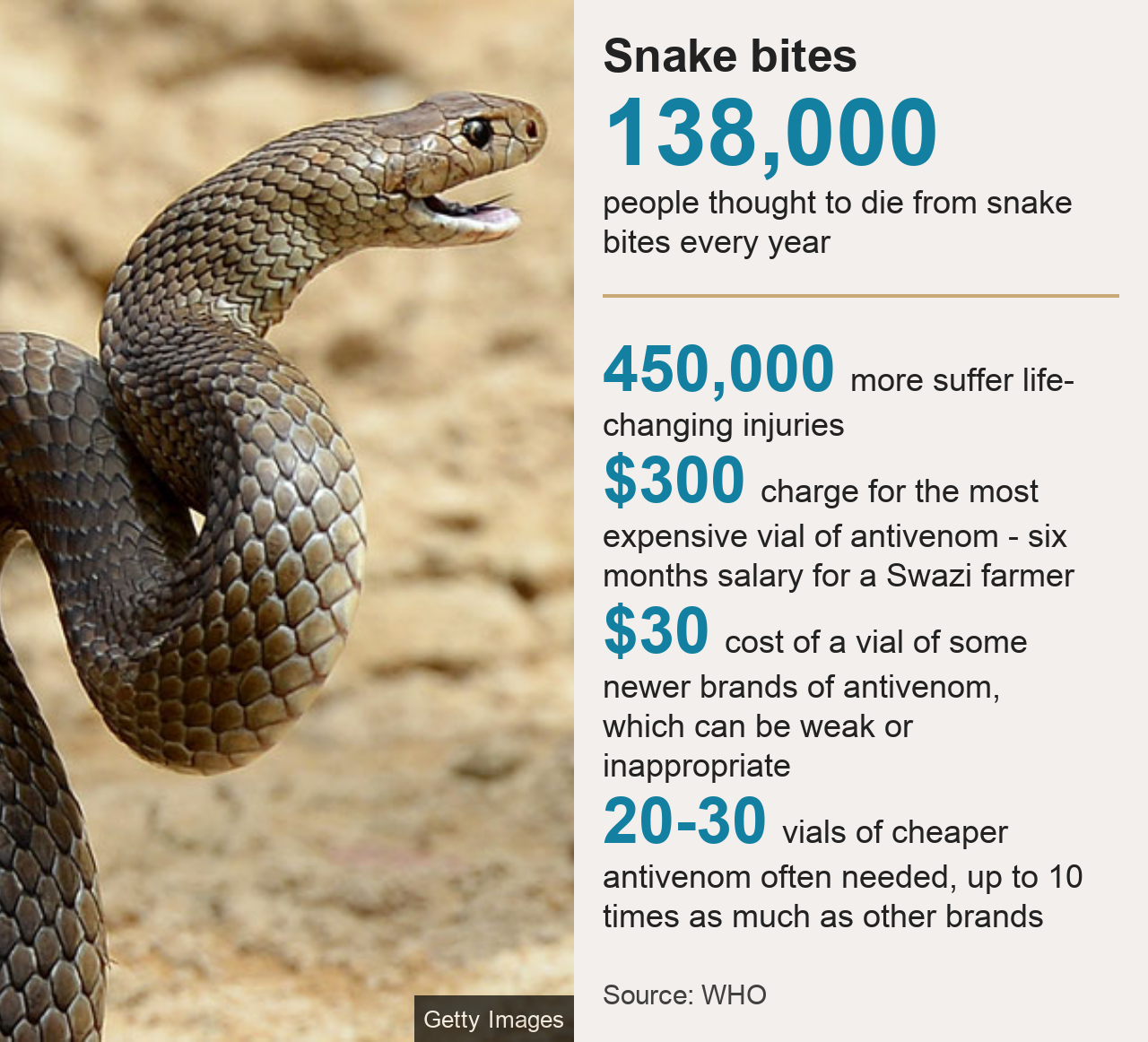

About 11,000 people a month are thought to die from venomous snakebites, external - similar to the number that died during the whole of the 2014-16 West Africa Ebola crises.

A further 450,000 people a year are thought to suffer life-changing injuries such as amputation and permanent disability.

The scale of the problem means snake bites are now classed as a priority neglected tropical disease.

Who gets bitten?

Children walking to school can be at risk of snake bite

In developed regions - such as Europe, Australia and North America - snake bites kill only a handful of people each year, despite there being many venomous species.

That is compared with 32,000 deaths in sub-Saharan Africa,, external and twice as many in South Asia.

Many rural communities in the tropics are at almost constant risk of snake bites, whether working in the field, travelling at dusk or even sleeping in their homes at night.

Young male farmers are the most at-risk group, followed by children.

While a large rural population is a factor, health systems in some parts of Africa and Asia are often ill-prepared for coping with snake bites.

Clinical training, emergency transport and affordable medicine are often in short supply, with tragic consequences.

Expensive medicine

Venomous snake bites typically cause three main types of life-threatening symptoms: uncontrollable bleeding, paralysis and irreversible tissue destruction.

It is essential for snakebite victims to get the correct medicine as soon as possible following a snake bite.

Antivenom is the medicine of choice for treating snake bites.

It is made using the venom of the snake it is designed to treat.

This means that many different versions are needed, because there are so many venomous snakes found throughout the world - cobras, mambas, kraits, vipers and pit vipers, to name just a few.

The toxins found in their venom differ from one group of snakes to the next, or even between the same group of snakes in a different region.

This means the correct antivenom is often hard to identify and can be very expensive.

How antivenoms are made

A tiny non-harmful amount of snake venom is injected into an animal - usually a horse, or sheep

This stimulates the animal's immune system to create antibodies that neutralise the venom

These antibodies are extracted from the animal's blood, purified and made into antivenom

Antivenoms must be used in hospital because of patients suffering a high rate of adverse reactions to the medicine

In Latin America, antivenom is often produced in the country and subsidised by the government., external

Death rates are significantly higher in sub-Saharan Africa, where the best antivenom costs $140 to $300 (£108 to £233) per vial, with three to 10 vials usually required to save a victim's life.

As the typical Swazi farmer earns $600 a year, this medicine out of reach for most.

The wrong antivenom

A juvenile pit viper

This situation has allowed weak or inappropriate medicine to flood the market over the past decade, particularly in Africa.

These antivenoms often cost about $30 per vial - a fraction of the cost of proven products.

Some African health ministries understandably saw this as a win-win situation, with more drugs available and at a lower cost.

These products started being used in hospitals throughout much of the continent.

However, there are now several reports that some of these medicines may be dangerously ineffective.

Small-scale case studies from hospitals in both Ghana and Central African Republic have suggested that when these cheaper medicines were used, fatality rates increased from 2% or fewer, to more than 10%.

Often, these antivenoms are made using snake venoms from a different region to where the product is being sold - for example an antivenom made with Indian snake venom being used in Africa.

Others are made with the right venoms, but with a low concentration of antibodies per dose - resulting in very weak medicines.

This means the number of vials needed to successfully treat the patient shoots up from three to 10, to as many as 20 or 30.

Ironically, this situation has prompted some established manufacturers to cut supply of their much-needed products as they became priced out of the market.

Lack of testing

An eyelash viper

These problems have been made worse by the lack of antivenom testing.

Most drugs have to be thoroughly independently tested, with clinical trials to prove their effectiveness.

But this often is not the case with antivenom. National drug agencies sometimes approve products without strong evidence of their effectiveness, or comparison with existing treatments.

To tackle this, the World Health Organization has launched a pre-market testing scheme,, external with the results due to be published later this year.

This should allow health ministries, pharmacists and clinicians to better understand which antivenoms are suitable for their region, while identifying responsible manufacturers of affordable antivenoms.

However, manufacturers do not have to take part in the scheme, and countries are not obliged to remove products from the market based on the results.

Nevertheless, it is hoped that this World Health Organization seal of approval will strongly influence antivenom purchasing decisions throughout Africa.

Looking to the future

Effective antivenom is one part of solving the snake bite puzzle, but many other challenges remain.

More work needs to be done to identify the communities most at risk and to ensure a sustainable flow of affordable medicine is sent there.

Meanwhile, training more clinicians and healthcare workers in how to effectively treat snake bite victims would reduce the number of deaths.

Finally, educating local communities about snake bites would help lower the risk of being bitten, and mean appropriate action was more likely to be taken after a bite.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from experts working for an outside organisation.

Dr Nicholas Casewell, external is a senior lecturer & Wellcome Trust research fellow at the Centre of Snakebite Research and Interventions (CSRI). You can follow him on Twitter here, external.

Dr Stuart Ainsworth , externalis a post doctoral research associate and lecturer on snakebite at CSRI. You can follow him on Twitter here, external.

Edited by Eleanor Lawrie

- Published26 May 2018