The strange normality of life in a breakaway state

- Published

A postal address is the marker that identifies our home's place in the world. The last line designates our country, from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe.

But for a few million people worldwide, that last line of the address is a problem. The international postal service does not recognise a letter marked Abkhazia, Trans-Dniester, or Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus.

Letters find their way after being re-routed via other countries. Open up the drop-down box of countries on an internet form and they are unlikely to be listed.

This trio of European statelets are among the few territories in the world, mostly formed by war, which exist on maps but are not full nation states, or members of international organisations.

However, they are self-governing and fairly stable. Life goes on - taxes are collected and children go to school. But it is all a little more complicated than elsewhere in the world.

Soldiers travel by bus through Tiraspol, the capital of Trans-Dniester

Of the world's contested states, Taiwan is by far the biggest. Yet despite it being independent to all intents and purposes since 1949, China regards it as part of its own territory which "must and will be reunited". It is recognised by fewer than 20 countries and is not a UN member.

At the other end of the scale, the Islamic State group proclaimed a state straddling Syria and Iraq which existed for three years, but was never recognised by any countries.

Abkhazia, Trans-Dniester (also known as Transdniestria or Transnistria) and northern Cyprus are somewhere in the middle. All three emerged out of conflicts which remain unresolved.

The breakaway region of Abkhazia won a war of secession with Georgia in 1992-93 and declared independence in 1999. In 2008, it was recognised by Russia - which Georgia considers an occupying force - and a handful of other states.

Trans-Dniester also emerged as the Soviet Union fractured into smaller states, breaking away from Moldova after a brief war in 1992.

Turkish Cypriots declared a state even earlier, in 1983, nine years after the political crisis and conflict in which Turkey invaded the north of the island. The UN continues to patrol the dividing Green Line and reunification talks have never succeeded.

A woman and her dog sunbathe next to the Black Sea border between Russia and Abkhazia

Each has a government and, although they are far from receiving international recognition, there is no sign of them collapsing.

This qualifies them as "de facto states" - places that govern their own territory, but which are outside the international system.

Importantly, all three of these breakaway territories have a powerful patron - Russia in the case of Abkhazia and Trans-Dniester, and Turkey in the case of northern Cyprus.

The patron helps them to survive - providing financial and military backing and stationing troops there.

But even if Russia or Turkey were to reduce support, these breakaway territories would not just melt away.

They would be weaker, but all would still retain a strong local identity and harbour aspirations to be separate.

A Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus flag painted on to a hillside in Nicosia, northern Cyprus

The international community does not think about these places very often - or the underlying problems that keep them in their strange state of limbo.

Interest in the de facto states is often from lovers of "places that don't exist", particularly in the cases of Abkhazia and Trans-Dniester.

Lack of formal recognition certainly leads to over-compensation in the production of state symbols.

They have developed quasi-state paraphernalia worthy of Freedonia - the Marx Brothers' fictitious state in Duck Soup - or the Republic of Zubrowka, from Wes Anderson's Grand Budapest Hotel.

Abkhazia prints exotic stamps with an eye on collectors around the world.

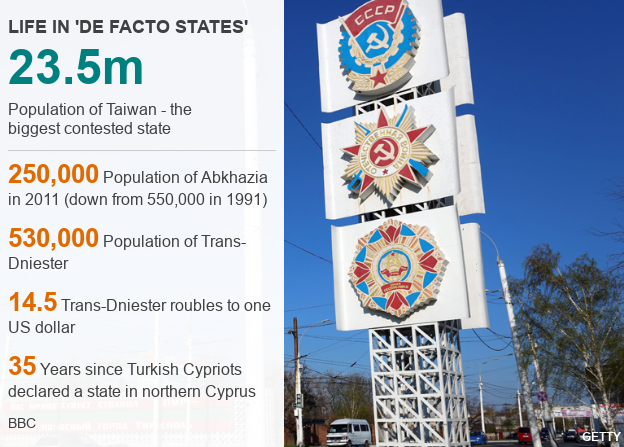

Trans-Dniester still has Soviet-era insignia on its symbols, such as the hammer and sickle. It prints its own currency, the Trans-Dniester rouble, which can only be used inside its borders.

Uniquely in the world it prints plastic coins in different shapes, which make them easily identifiable for blind people, and which fetch high prices on eBay.

Yet while they may be idiosyncratic, it is a stretch nowadays to call the trio "rogue states".

That is not to say they are without problems. Human trafficking, for example, is a big issue in both northern Cyprus, external and Trans-Dniester, external.

Yet the main impression a visitor to these places would have is of their ordinariness.

A group of boys swimming at the Black Sea in Abkhazia

All have traffic lights, traffic police, hospitals and other trappings of more "normal" states.

Shoppers sit in cafes glancing at smartphones - even if the coffee they drink is not brewed by a global brand like Starbucks.

And despite their home state having almost zero prospect of wide international recognition, people have the same goals as those anywhere else.

Businesses want foreign trade, students want scholarships abroad.

The states follow many European norms voluntarily. None of them has the death penalty and all hold quite strongly competitive elections - even if the pool of candidates is quite limited.

A group of men play Okey in Nicosia, northern Cyprus

However, a place cannot live by postage stamps alone - it needs to collect those tax revenues and to make sure the police force and school system work.

That gives the outside world and would-be conflict mediators some leverage and influence - something that is only being used to a limited extent at present.

Offers of help with education and health could be accompanied by calls for co-operation on the extradition of fugitives, for example.

To a degree that is already happening with Trans-Dniester, which has quietly signed up to Moldova's free trade agreement with the European Union.

It has also made an agreement that means cars from Trans-Dniester can travel abroad with neutral-looking number plates registered in Moldova. And diplomas from Trans-Dniester's main university can be registered internationally.

Visually the place may still look like a Soviet theme park, with its statues of Lenin and hammers and sickles, but it is actually moving in another direction.

As one former official said to me: "My head is in Russia, but my legs are moving towards Europe."

Young women at an ice cream stall in Trans-Dniester

With full resolution of these disputes still far off, this model of incremental change and international engagement offers an alternative way forward.

If the three territories will not be reintegrated into their parent states of Cyprus, Georgia and Moldova in the near future, at least their residents - but not their governments - could become part of the global community.

Without giving them recognition, de facto states can be more predictable and better aligned with their neighbours.

Over the longer term, the deep-rooted conflicts that created these de facto states could be a little bit easier to overcome.

Just do not hold your breath. They promise to be around for a long time to come.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

It is based on Uncertain Ground: Engaging With Europe's De Facto States and Breakaway Territories, external, by Thomas de Waal, external - a senior fellow with Carnegie Europe, specializing in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus region. Follow him @Tom_deWaal, external.

Edited by Duncan Walker

- Attribution

- Published20 November 2018