Myanmar Rohingya: How a 'genocide' was investigated

- Published

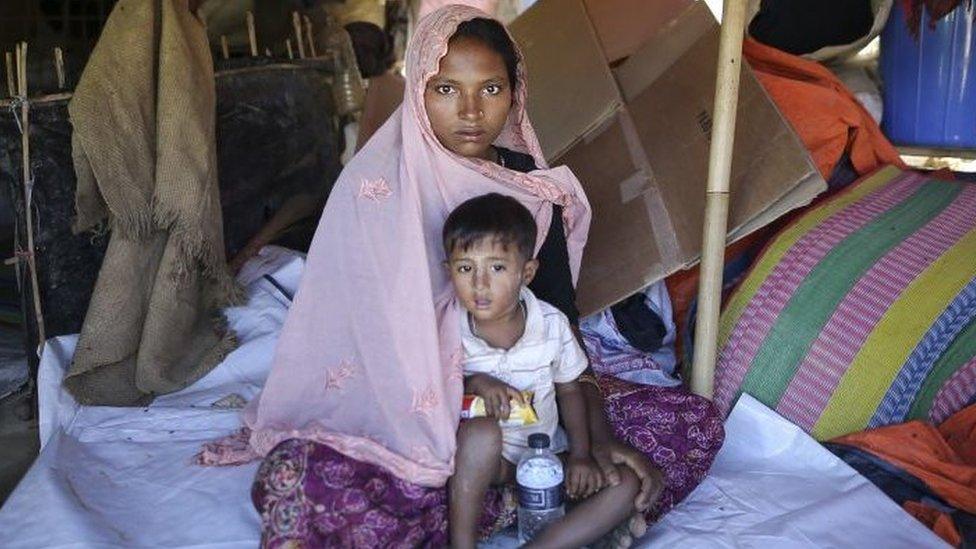

About 725,000 Rohingya Muslims have fled Myanmar over the past 12 months, many for Bangladesh

Indiscriminate killing; villages burned to the ground; children assaulted; women gang-raped - these are the findings of United Nations investigators who allege that "the gravest crimes under international law" were committed in Myanmar last August.

Such was their severity, the report said, the army must be investigated for genocide against the Rohingya Muslims in the western Rakhine state.

The investigators' conclusions came despite them not being granted access to Myanmar by the government there, which has since rejected the report.

This is how the investigators came to their conclusions.

The build-up

On 24 March 2017, the UN Human Rights Council agreed to form an independent fact-finding mission on Myanmar to look into "alleged recent human rights violations by military and security forces".

Five months after the mission was formed, Myanmar's army launched a major assault on Rakhine state, following deadly attacks by Rohingya militants on police posts.

The military's campaign became the main focus of the investigation, which also looked into rights abuses in Kachin and Shan states.

The mission wrote to Myanmar's government three times asking for access to the country. It received no response.

The interviews

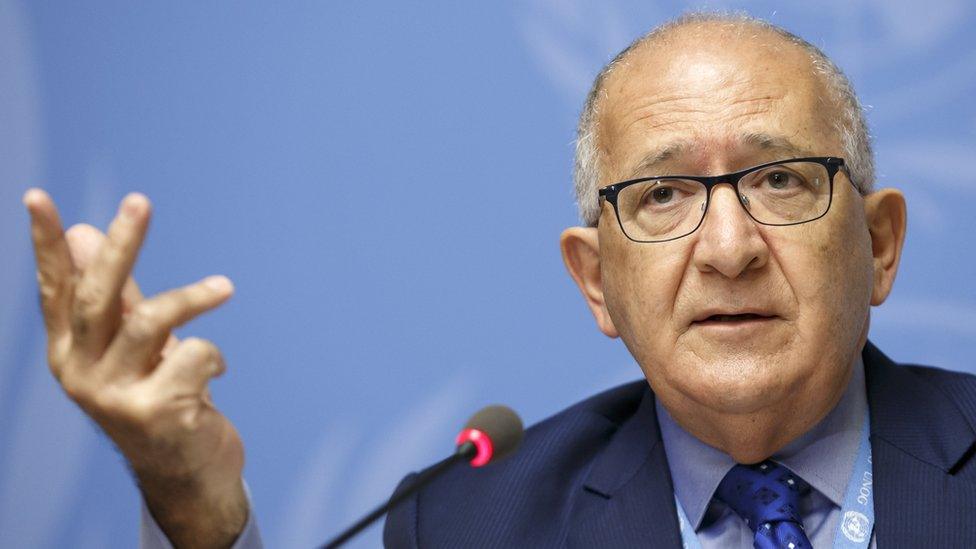

"The first rule was 'do no harm'," says Christopher Sidoti, one of the three people who headed the investigation.

"Those people we spoke to had been heavily traumatised, and if our staff considered that an interview would be re-traumatising, it wouldn't have been conducted.

"No evidence is so important that it warrants re-traumatising someone who has gone through all these experiences."

At least 725,000 people have fled Rakhine state over the past 12 months, many to neighbouring Bangladesh. As a result, despite not getting access to Myanmar, investigators were able to gather a vast amount of testimony from people who had experienced violence at first-hand before fleeing.

Many made the treacherous journey from Rakhine to Bangladesh by sea

They spoke to 875 people in Bangladesh, Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia and the UK, and made a decision early on that the most valuable testimony would come from people who had not shared their stories before.

"We didn't want to interview people who had been interviewed by other organisations," Mr Sidoti, an Australian human rights law expert, says. "We didn't want a situation where people's evidence could have been tainted.

"We tried to get people from a wide variety of areas and when we became more and more focused later on, we would deliberately, through a community network, seek out others from that area to get a better picture of what went on."

The evidence

"We would never use just one account as proof," Mr Sidoti says. "We always sought corroboration from primary and secondary sources."

Those sources included videos, photographs, documents and satellite images, which showed the destruction of Rohingya villages over several months in 2017.

In one case, investigators had received several reports from refugees in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh, that a village had been destroyed in particular circumstances at a particular time.

Investigators were then able to source satellite images that corroborated what witnesses had said.

Satellites images showed that:

About 392 villages were partially or totally destroyed in northern Rakhine state

Close to 40% of all homes in the area - 37,700 buildings - were affected

About 80% were burned in the first three weeks of the military campaign

Rohingya girls in danger: The stories of three young women

Getting hold of photographic evidence from the ground proved to be more of a challenge.

"When people were leaving Rakhine state, they were being stopped, searched and deprived of their money, gold and mobile phones," Mr Sidoti says. "It seemed pretty clear this was an attempt to get video or photographic evidence they had recorded.

"There wasn't much left but we made use of it."

The accused

The report names six senior military figures it believes should go on trial, including Commander-in-Chief Min Aung Hlaing and his deputy.

How were investigators able to point the finger directly at these men?

The case here is not based on a paper trail, or a recording, but instead on research.

Investigators relied heavily on others' detailed understanding of how Myanmar's government works. Among them was a military adviser who had co-operated with war crimes tribunals in the past.

"We have been able to access extraordinary international advice on various aspects of Myanmar's military," Mr Sidoti says. "The conclusion we have come up with is that the army is so tightly controlled that nothing happens involving the army in Myanmar without the commander-in-chief and his deputies knowing."

While the people believed to have given the orders have been named, work is ongoing to identify the members of the military who may have committed atrocities.

"We do have a list of alleged perpetrators on the ground and they will remain confidential for now," Mr Sidoti says. "Their names have come up frequently enough for them to be put on lists to face more investigation."

The law

Identifying what appears to be genocide and proving that what happened fits the legal definition of genocide are two different things.

"Evidence of crimes against humanity was very quickly obtained and was quite overwhelming," Mr Sidoti says. "Genocide is a much more legally complex issue."

Christopher Sidoti: "None of us thought the evidence for genocide would be as strong as it was"

As the report states, genocide is when "a person commits a prohibited act with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group".

The key word is "intent". Investigators believe the evidence of that intent by the Myanmar army is clear.

They cite statements by commanders and suspected perpetrators, and the degree of planning required to carry out such an operation. But still, identifying a genocide from a legal perspective took a significant amount of legal work.

"We arrived at a position we had not expected to be in when we were beginning," Mr Sidoti says. "None of the three of us thought the evidence for genocide would be as strong as it was. That came as a surprise."

The next step

The report says that the six military officials should face trial. It also condemns Myanmar's de facto leader, Nobel Peace Prize laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, for failing to intervene to stop attacks, and the UN's outgoing rights chief this week said she should have resigned as a result.

The report also makes a series of recommendations, including the referral of the investigation to the International Criminal Court or to a new tribunal, and the imposition of an arms embargo.

However, China has so far resisted strong action against its neighbour and ally Myanmar on the UN Security Council, where it holds a veto.

Mr Sidoti acknowledges that officials in Myanmar are unlikely to investigate the allegations themselves. Last year, an internal investigation by the army exonerated itself of blame in the Rohingya crisis, and Myanmar's Permanent Representative to the UN last week told BBC Burmese the report was full of "one-sided accusations against us".

"We have made recommendations and it is up to others to act on them," Mr Sidoti says. "I have a high expectation that the Security Council will act on its responsibilities. But I'm not naive."

- Published27 August 2018

- Published29 August 2018

- Published6 September 2017

- Published14 November 2017

- Published23 January 2020