Violence against women: The stories behind the statistics

- Published

Rebecca Skippage, Nel Hodge, Maryam Azwer and Vesna Stancic (L-R) were part of the team who collected the stories.

As the UN publishes new data about violence against women, BBC Monitoring explains how they worked to find out more about the circumstances in which women died on one day in 2018.

Six months ago, the BBC 100 Women team came to us with a bold idea: Could we find every report of a woman who died in a gender-related killing on one day across the world's media?

We felt we were well placed to do this.

BBC Monitoring, external has been tracking the world's media for 80 years. Every day, our network of journalists in 13 international bureaux observe, translate and analyse TV, radio, print, online and social media.

We scan thousands of sources, work in more than 100 languages and cover more than 150 countries to make sense of what's happening on the ground around the world.

But despite our experience in media observation, this was not something that we - or, we believe, anyone - had done before.

It was not only about ensuring editorially robust data-gathering; it was about surfacing as many of the individual stories as we could find.

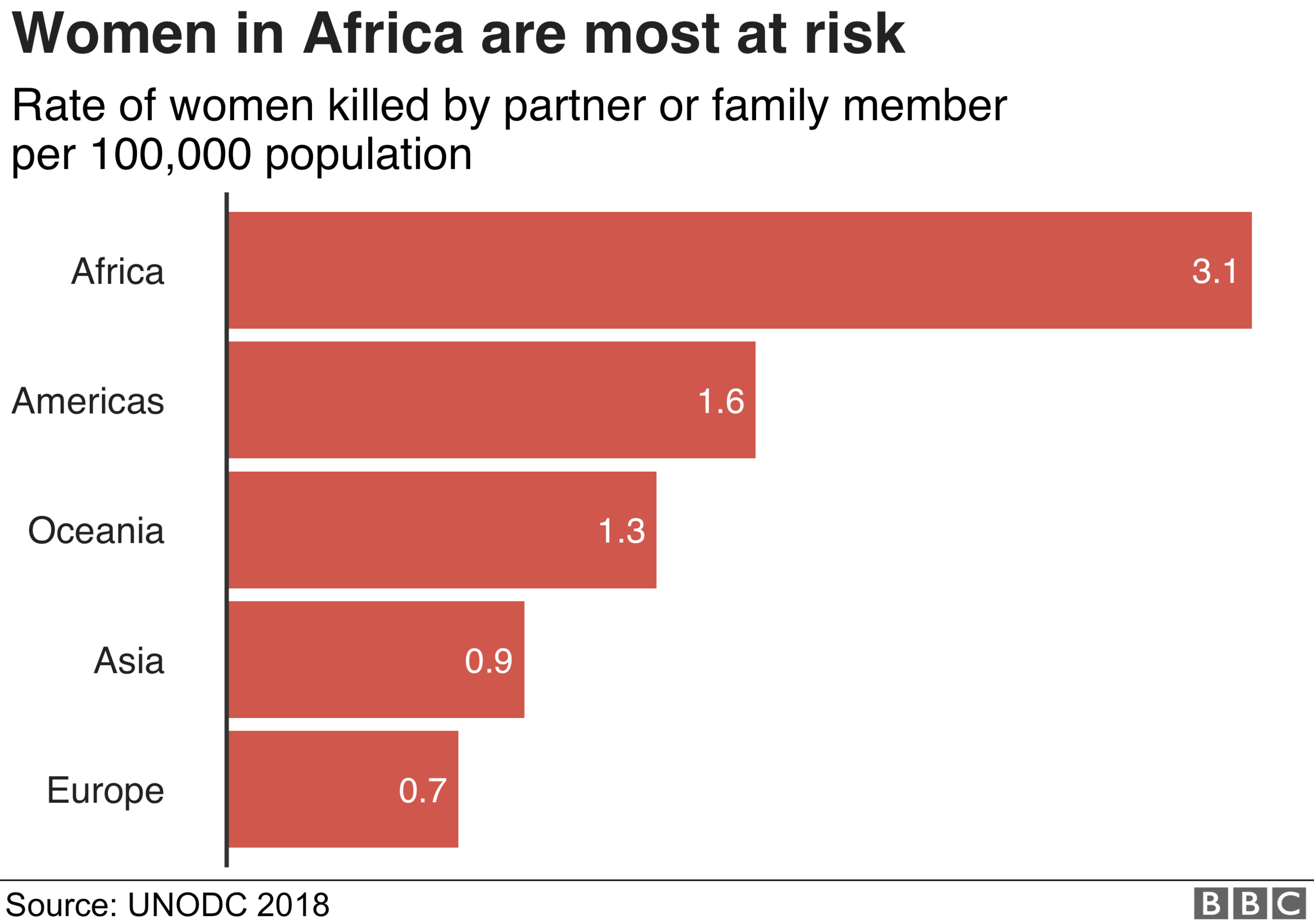

New UN data suggests an average of 137 women across the world are killed by a partner or family member every day.

First, the practicalities: We chose, at random, a date - 1 October 2018 - and divided the world into sections.

Then BBC Monitoring journalists from Delhi to Miami scanned a range of media sources in their usual "patches" for killings committed on that day.

We extended our monitoring into other regions - including areas of the English-speaking world - that our unit doesn't normally cover.

We commissioned researchers and freelancers to listen to radio stations in far-flung places and scour local papers to find credible reports of women and girls being killed because of their gender.

Their work was fed back to a small London-based central team, who checked and collated the information.

For some countries, our most useful data-gathering tools were eyes and ears.

For others, we turned to technology. To complement the research happening in person, our innovation team in London used AI and machine-learning programmes to search more media sources than the human eye could realistically scan.

Finding reports brought hugely mixed feelings. Each was a woman who had lost her life. But finding it allowed us to shine a light on the life she had lived.

Vesna Stancic in the London team explained: "It's the first time that finding something I was looking for didn't bring a sense of achievement; instead it was tinged with sadness for the women and girls."

Matilda Welin, who looked at Scandinavian media, added: "It felt horrible to input the terrible search phrases in five languages. But as long as it was done respectfully, I thought that the BBC could use the story to help stop others from suffering."

It was that sense of purpose that drove this research. We were looking for cases of women and girls killed within one day, but we searched for that day's stories for a month.

We found that the time-lag in reporting, the tone of the coverage, or the scarcity of information often told a wider tale about the status of women in that region.

Wanjiku Mungai and Beverly Ochieng who researched stories in Africa.

Wanjiku Mungai, based in Nairobi, was surprised at the "relative silence" about killings in the local press. That's despite the continent having the highest rate of women reported as killed by a partner or family member in the world in 2017, according to the new data from United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

"Cases were not reported often. When they were, they tended to be tied to an issue of broader interest, such as the 'sponsor culture' [younger women linked to older, wealthier men] or ritual murder."

Her colleague Beverley Ochieng added:

"Whenever a case involved physical or sexual assault, media tended to dwell on the graphic details. Where photographs accompanied reporting, some of the victims were sexualised. At times a moral tone almost seemed to suggest that victims were 'deserving' of their deaths."

Africa is where women run the greatest risk of being killed by their intimate partner or relatives, the UN report says.

In Latin America, the killing of women because of their gender has become an increasing concern for many governments.

On 19 November, it was reported in El Salvador that all killings of women would be investigated as femicide - the gender-related killings of women and girls.

Blaire Toedte, researching Latin America, found 14 cases of women killed on 1 October 2018 - four of whom remain unnamed:

"Some sources described the women's deaths in gruesome detail; others were quite blunt."

At the heart of this project we were trying to answer a simple question: How many women and girls were killed on one day? We found reports of 47.

But what we found was that behind that number, the way in which the media reported their lives and deaths revealed a huge amount about how women are viewed by different societies around the world.

Maryam Azwer drew much of the final data together:

"This is as much about the deaths that aren't reported, as those that are. Those whose stories never reached the media, that went unreported, were unverified, or were not or could not be investigated.

"It makes you wonder: what does it take to make a woman's killing important enough to be reported?"

Help and advice

If you, or someone you know, have been affected by domestic abuse or violence, these organisations in the UK may be able to help.

Outside the UK, there are other organisations which provide advice and protection for people at risk of violence or abuse. If you feel in danger, try to find out which local organisations can best advise and help you.