John Allen Chau: Do missionaries help or harm?

- Published

How should the world view missionaries?

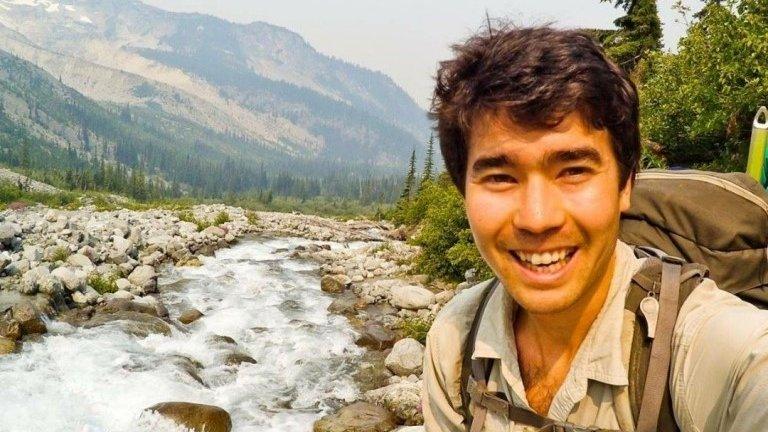

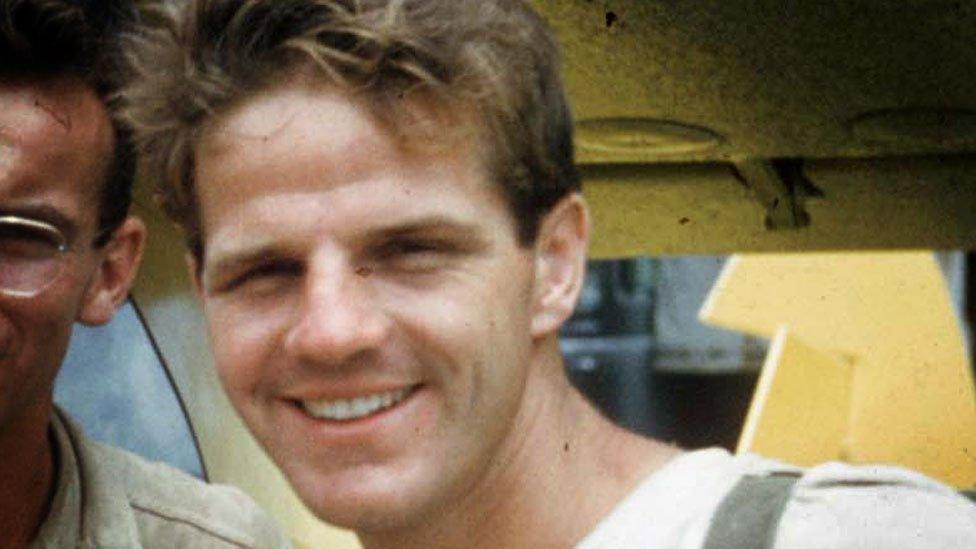

"You guys might think I'm crazy in all this... But I think it's worth it to declare Jesus to these people."

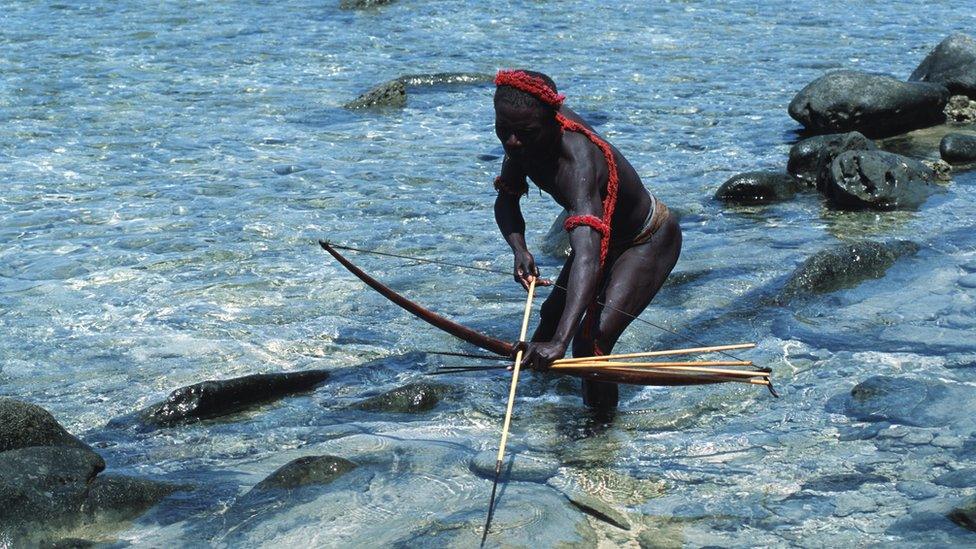

These were some of the last words in the final letter John Allen Chau sent to his parents, external before he was killed by the people of North Sentinel Island last week.

While he was not himself a missionary, Chau did say that his aim was to bring the gospel to the tribe.

And his attempts to do so have brought into focus the hundreds of thousands of Christians around the world spreading their faith.

But who are these missionaries? What do they hope to achieve? And are they a positive force around the world, or an unwelcome presence?

What is a missionary?

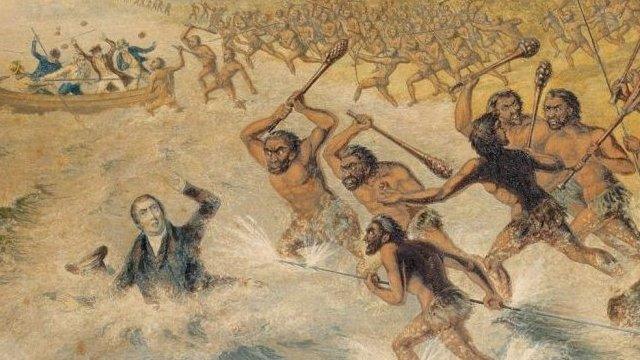

While other religions have sent missionaries around the world, none are more widespread or well-known than Christian missionaries.

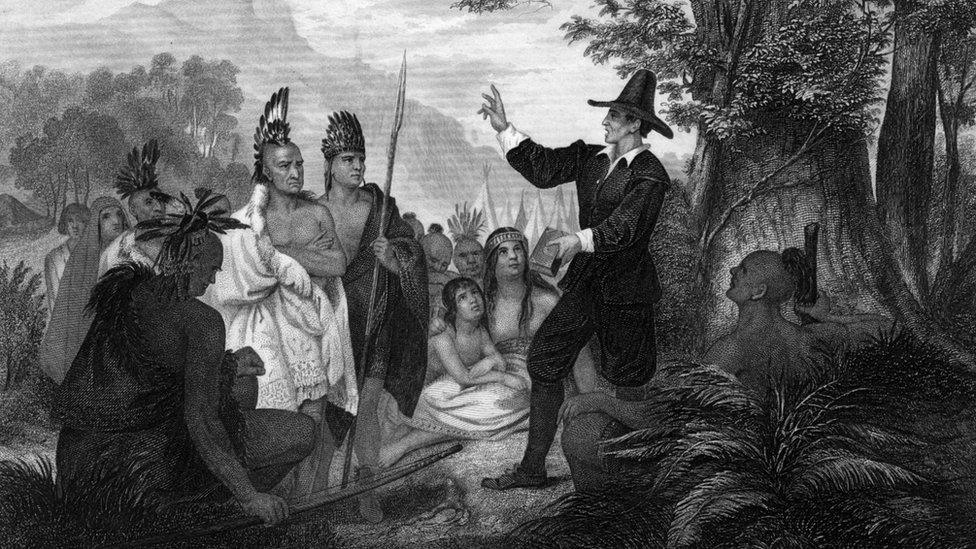

Missionaries of all Christian creeds cite a passage in the Bible, the most famous of which appears in the Book of Matthew, in which Jesus asks his followers to "make disciples of all nations".

Christian missionaries have worked worldwide for centuries

This passage is known to missionaries as the Great Commission, and is held to be some of Jesus' final instructions to his disciples before ascending to heaven.

Religious people were often at the vanguard of colonial efforts. Spreading religion was seen as a way to "civilise" people outside of Europe and the US.

Over time, this turned to physical as well as spiritual development.

"However much this might be a trigger for conversations about missionary projects, John Chau is not a representative evangelical," David Hollinger, retired professor emeritus at the University of California at Berkeley, tells the BBC. "He's anomalous."

"Evangelicals are still proselytising [trying to convert], but they're now also building hospitals and schools," he says. "A lot have very strong service projects."

According to the US Centre for the Study of Global Christianity, there were 440,000 Christian missionaries working abroad in 2018, external.

This number includes Catholics, Protestants, Orthodox Christians and North American groups like the Jehovah's Witnesses and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (LDS Church), known as Mormons.

The LDS Church is one of the few that runs a centralised missionary programme. On their own, Mormon missionaries number nearly 66,000 worldwide, external and over the course of its history, the Church has sent out more than one million missionaries, external.

In 2017, the Church says its missionaries baptised 233,729 new converts, external.

What do missionaries do?

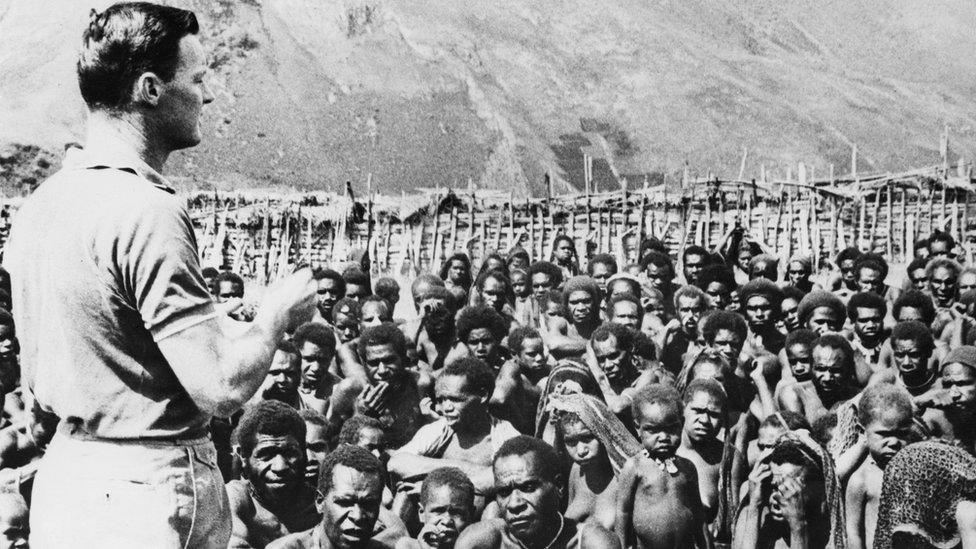

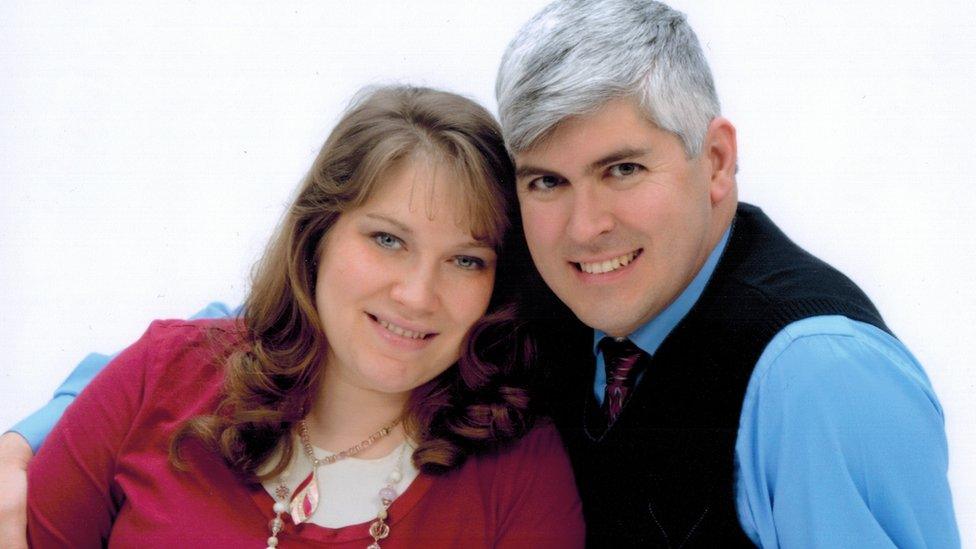

John Allen (no relation of John Allen Chau) and his wife Lena - a registered midwife and nurse - have worked as Christian missionaries in Papua New Guinea for 15 years.

The American couple "seek to promote Christian values and a transformational Gospel model," Mr Allen tells the BBC via email.

"It isn't about getting people to believe like we believe," he writes. "It is about people seeing for themselves, from the Bible, that God has a plan for mankind in general and everyone in particular."

The couple set up a medical clinic 10 years ago to help the Kamea people of Gulf Province, where they live.

Five PNG nationals and three American nurses work with them at the Kunai Health Centre, and as well as treating illnesses and wounds, the team have set up a number of programmes for expectant mothers and new-born babies.

Allow Facebook content?

This article contains content provided by Facebook. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Meta’s Facebook cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Mr Allen says the pair are fluent in the trade language, Tok Pisin, and are studying the Kamea language - an unwritten dialect until 2009, when the couple began to note it down.

"It is very difficult to learn, as we are the ones writing and documenting it," Mr Allen says. "From what we know... no outsider has been completely fluent yet."

"Not all mission work today is of the same nature; this happens to be what we are doing," he explains.

Andrew Preston, the professor of American history at the University of Cambridge, says that even historically, some missionaries were at the forefront of learning languages.

"It's less true now than it used to be," he tells the BBC. "But 100 years ago, missionaries were the only ones who had fluency not just in obscure African or Asian languages but even Chinese and Japanese."

And while Mr Allen describes local customs as "a constant learning experience," it is something to which they are committed.

"The best way to learn about a people is to sit in the mud with them, eat their food with them, sleep in their huts with them, rejoice in their joys with them, and go through their burdens with them," he says.

"It is then that you begin to appreciate your new family and begin to view their culture through their eyes."

Allow Facebook content?

This article contains content provided by Facebook. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Meta’s Facebook cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Scott and Jennifer Esposito, meanwhile, work as non-denominational missionaries in Nicaragua. They run a farm, a sports programme and Bible study groups to spread their faith.

"We're constantly just sharing the Gospel," Scott tells the BBC on the phone. The couple intentionally do not count how many they have converted, but estimate they have brought somewhere between 800 and 1,200 people to their faith in the past six years.

"Every soul matters," Scott says. "When you start to count and set goals, say, you want 500, you become so goal-driven and numbers-driven that you pass by that one person who's so important they might take a long time."

What do they think of John Chau?

"When John Chau's story broke here, it was like, 'Wow, we had thought of doing that'," missionary John Allen says.

While he personally did not think of going to the islands, he speaks of colleagues of his who had talked of approaching the Sentinelese people.

"Though they weren't seriously considering it, they tossed around ideas of how to approach the people safely, how to begin to make friendly contact, how to minimise their "footprint" while at the same time reaching out to them to learn their language and culture," he says.

On 21 October, @johnachau posted that he was travelling to the region

Both Mr and Mrs Esposito believe what happened to John Chau was tragic. They are aware that some people deem his actions foolish, and that there are others who support them.

"I would hesitate to cast a stone one way or the other with him," Jennifer Esposito says. "From everything I've read he loved the Lord - his sacrifice may bring many to Christ in the future.

"Who knows what seeds [have been planted] or what bigger things are going to happen."

Mr Esposito believes that if a team of doctors had broken those laws and customs to save the tribe from an illness, the reaction would have been different.

How a group of missionaries were killed in the Amazon in the 1950's

"If these doctors were to go and in the process get killed, I think most people around the world would say those were brave people," he says. "[John Chau] went to save their eternal lives."

That said, Mr Esposito does not condone breaking laws as John Chau did, and says they are "very respectful" of local laws and customs.

"We should all copy his heart, in the sense that he was willing to die, but I don't think everyone should be seeking out dangerous tribes necessarily."

Is missionary work a form of imperialism?

Caitlin Lowery wrote a Facebook post in the days after John Chau's death.

"I used to be a missionary," the post reads. "I thought I was doing God's work. But if I'm being honest, I was doing work that made me feel good."

"This is white supremacy. This is colonisation."

Allow Facebook content?

This article contains content provided by Facebook. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Meta’s Facebook cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

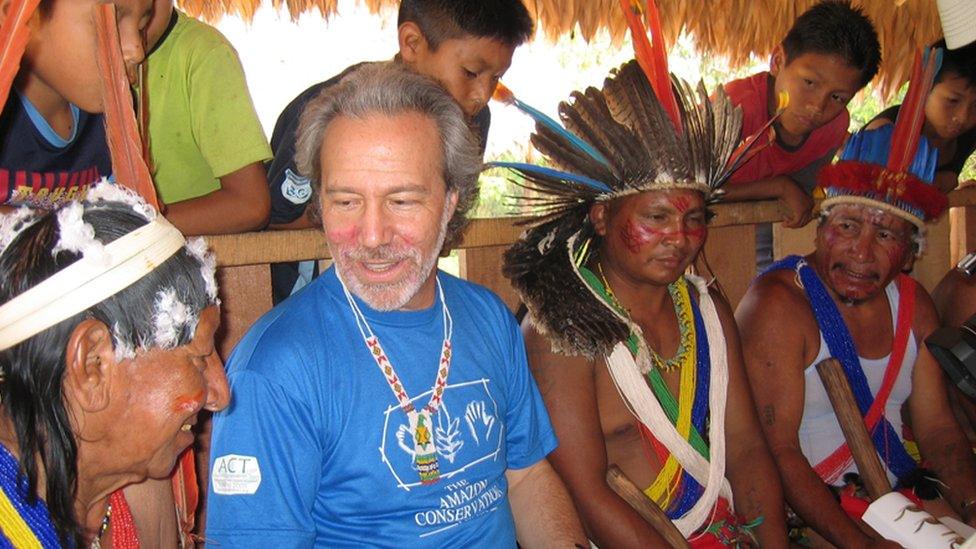

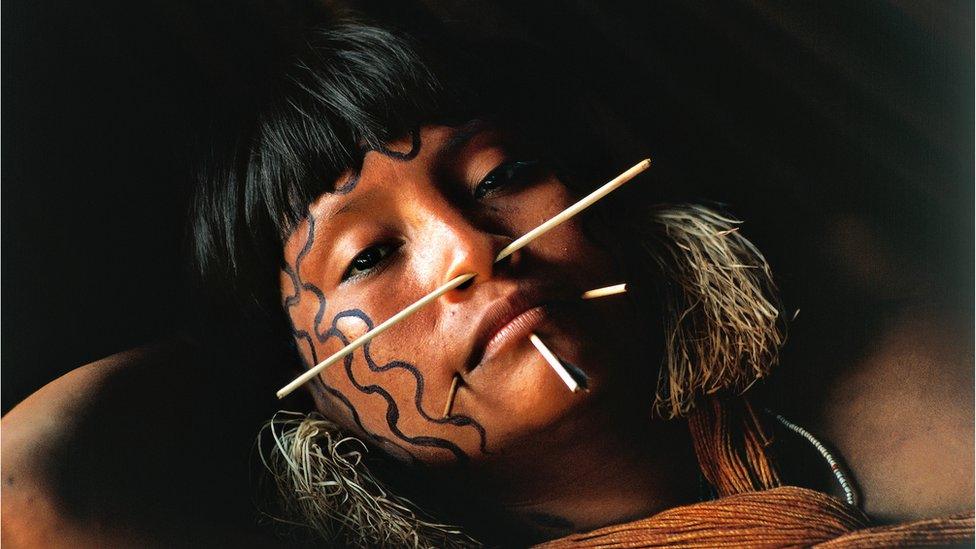

Mark Plotkin is a botanist and co-founder and president of the Amazon Conservation Team. The group works with the Colombian government to protect isolated peoples.

"I've worked for 30 years in the Amazon and I've seen there are two types of missionaries," he tells the BBC - those who want to "prepare these tribes for the outside world", and those who want "to save some souls for Jesus".

He says that while missionaries do truly believe they are making the world a better place, their work can be extremely harmful.

"Dragging uncontacted people out of the jungle for their own good is sometimes not for their own good," he told the BBC.

He speaks of the Akuriyo people in Suriname, who were contacted by missionaries in 1969. Within two years, Mr Plotkin says, "40 to 50% of the Akuriyo were dead" due to respiratory diseases, but also due to what Mr Plotkin suspects could be stress or "culture shock".

"They were seeing people wearing clothes for the first time and giving them injections," he says.

"Nobody should play God."

Mark Plotkin works to protect isolated indigenous people

Countries worldwide have taken a dim view of missionary work.

Proselytising is illegal in Nepal, and in August the law reportedly changed to state that foreigners convicted of the crime can be deported, external after a maximum jail sentence of five years.

Historically, Prof Preston says some, but not all, US Protestant missionaries came to develop an "ambivalence to empire".

"They realised they were a part of US hard power, they couldn't escape that." Because of that link, some missionaries came to promote local identities and nationalist causes - even when it ran counter to US aims.

"There were still plenty of American exceptionalists," he says, who believed the US was unique among nations. "But a lot of them wanted to improve the world on Christian, not American lines."

Mr Allen agrees that this association can be difficult, saying he feels "disgusted" when he sees any form of colonialist action in missionaries or even businessmen.

"Some days, no matter how hard we try, we seem to get unnecessary deference," he says, explaining they strive to build "genuine relationships based on mutual trust and respect".

"I'm not naive enough to think I'll ever be Kamea, but our team on the ground strives to work toward dismantling any colonial leanings and replacing them with co-dependent friendships."

- Published27 November 2018

- Published24 November 2018

- Published23 November 2018

- Published31 October 2018

- Published15 October 2018

- Published13 October 2018

- Published28 November 2018

- Published12 April 2018