Crossing Divides: What the research tells us

- Published

While social research generally suggests people tend to have friends who are similar to them, respondents told a poll for the BBC their social circles were much more diverse.

Ipsos Mori surveyed about 20,000 people, external with internet access in 27 countries about their friendship groups, with a majority saying they were inclined to embrace differences.

Half agreed it was important to listen to others who were different from them - even if they disagreed with the other person.

However, not many people said they did this on a regular basis.

"There is a gap between what we think is good for society, versus what we actually practise," says Ipsos Mori's Glenn Gottfried, who oversaw the research.

What did people say?

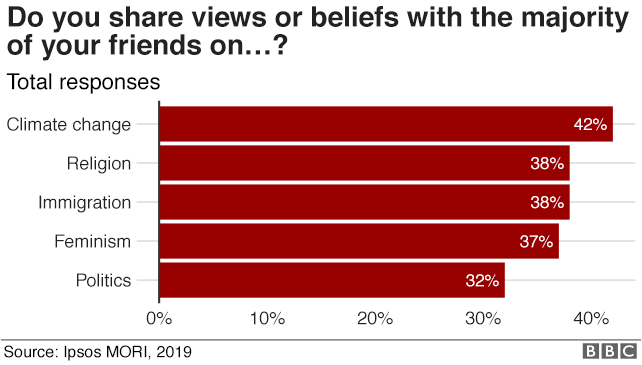

Across the countries polled, around two in five respondents said a majority of their friends had similar views or beliefs to them in terms of climate change (42%), religion (38%), immigration (38%) and feminism (37%).

However, the numbers dropped when they were asked about political views.

Over 35% claimed to speak to people with opposing views on at least a weekly basis.

About a fifth said they had such conversations less than once a month, with one in 10 suggesting they never did.

These findings replicate recent polling on post-truth and the internet, external, which showed 65% of people think that others across the world live in an online bubble but only 34% admitted to living in similar bubbles themselves.

Not tried our quiz yet? Give it a try...

See how your answers compare with those of people who took part in the survey:

How do we perceive our friends?

More than half (56%) of all participants said the majority of their friends were of the same ethnicity, while 46% said most were of the same age group.

This is in line with a growing body of evidence that suggests that we tend to make friends with people who are similar to us, analysts say.

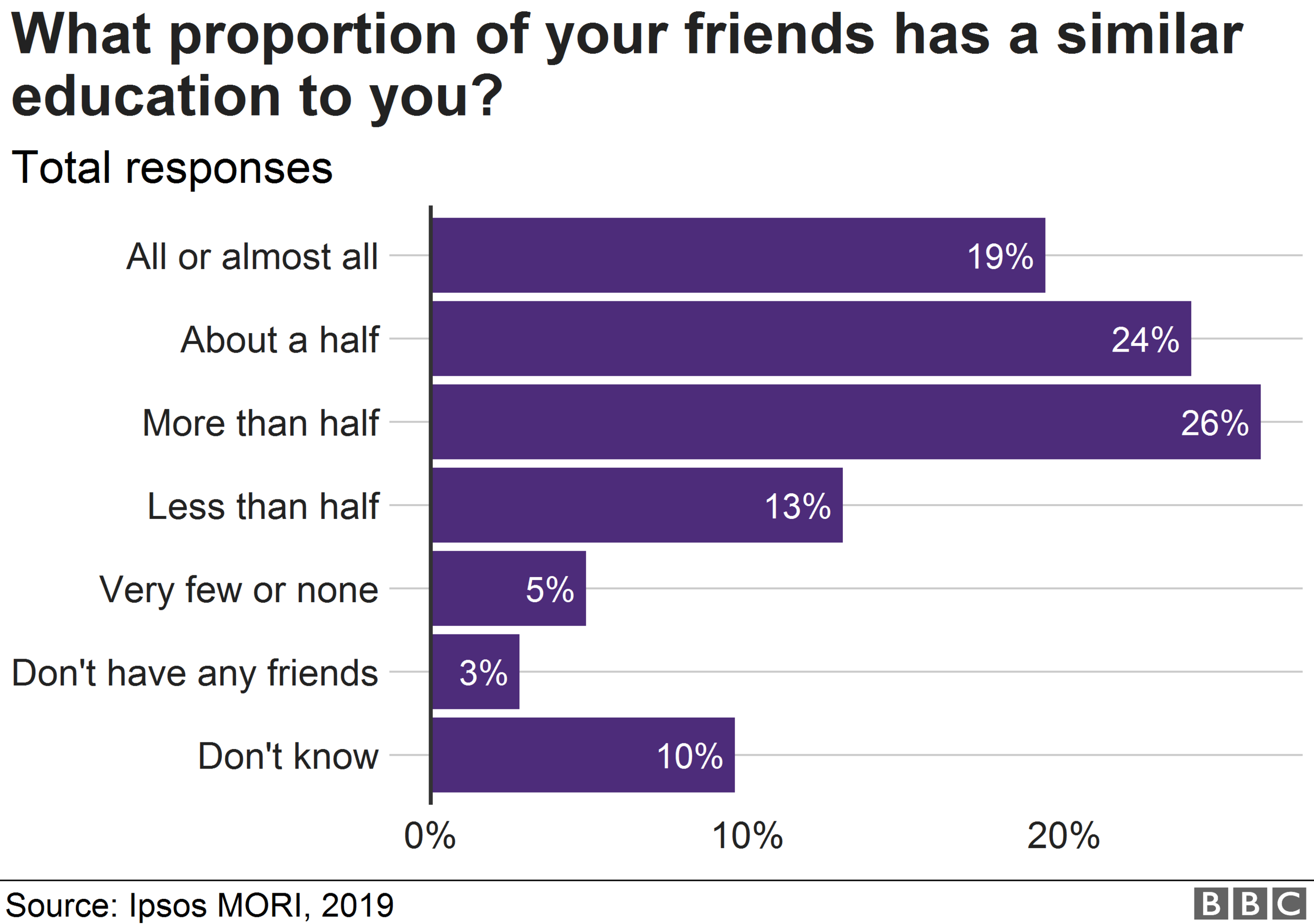

The same can be said about education: globally, a majority report finding like-minded souls among people with similar educational attainment.

However, this drops dramatically when discussing levels of income.

Only 30% of respondents said they are in the same income bracket as the majority of their friends.

An income gap - sometimes established later in life and not necessarily related to education levels - is no bar to friendship, the poll suggests.

But Alison Goldsworthy, founder of US research group The Depolarization Project, external, sounds a note of caution.

"People lie all the time about how much they earn," she says.

"Their friends may have no idea and (especially in some cultures) people are unlikely to discuss this in their social interactions."

Do friends agree on the big issues?

Just under a third of respondents said they shared their political views with most of their friends, with only one in 10 of those who took on the question responding "all" or "almost all".

"It is important to identify that people think their groups are more politically diverse than they actually are," says Ms Goldsworthy.

This may partly be because the political divide is often more openly addressed than other social differences.

"For instance, it's [perceived as] OK to see those who are different politically in a hostile manner in a way that is not acceptable when it comes to race, gender or religion," Ms Goldsworthy adds.

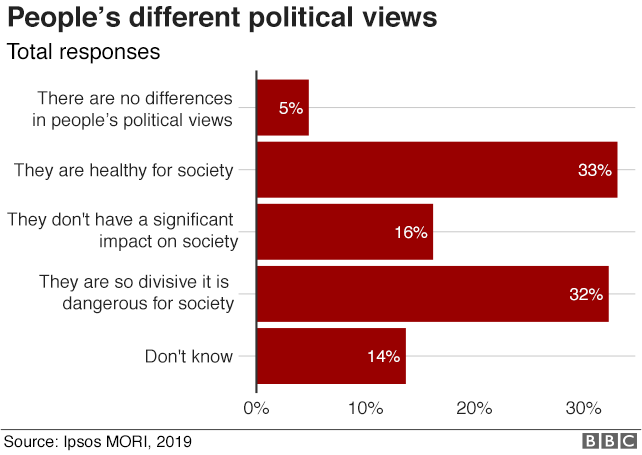

While more than 80% of respondents perceived the political divisions in their social circles, they were split over whether these were positive or detrimental.

A third thought these differing views are a healthy sign of a diverse society, while a similar proportion (32%) thought they are so polarising they could be dangerous.

A growing body of research suggests we tend to make friends with people similar to us

Also, more than 40% of those polled thought society is more in danger now than it was two decades ago because of divisions along political lines, with only 14% thinking the opposite.

"Politics is a thorny issue in people's social circles," says Ipsos Mori's Glenn Gottfried.

"These are times in which politics are changing and people recognise that they are becoming more divisive," he adds.

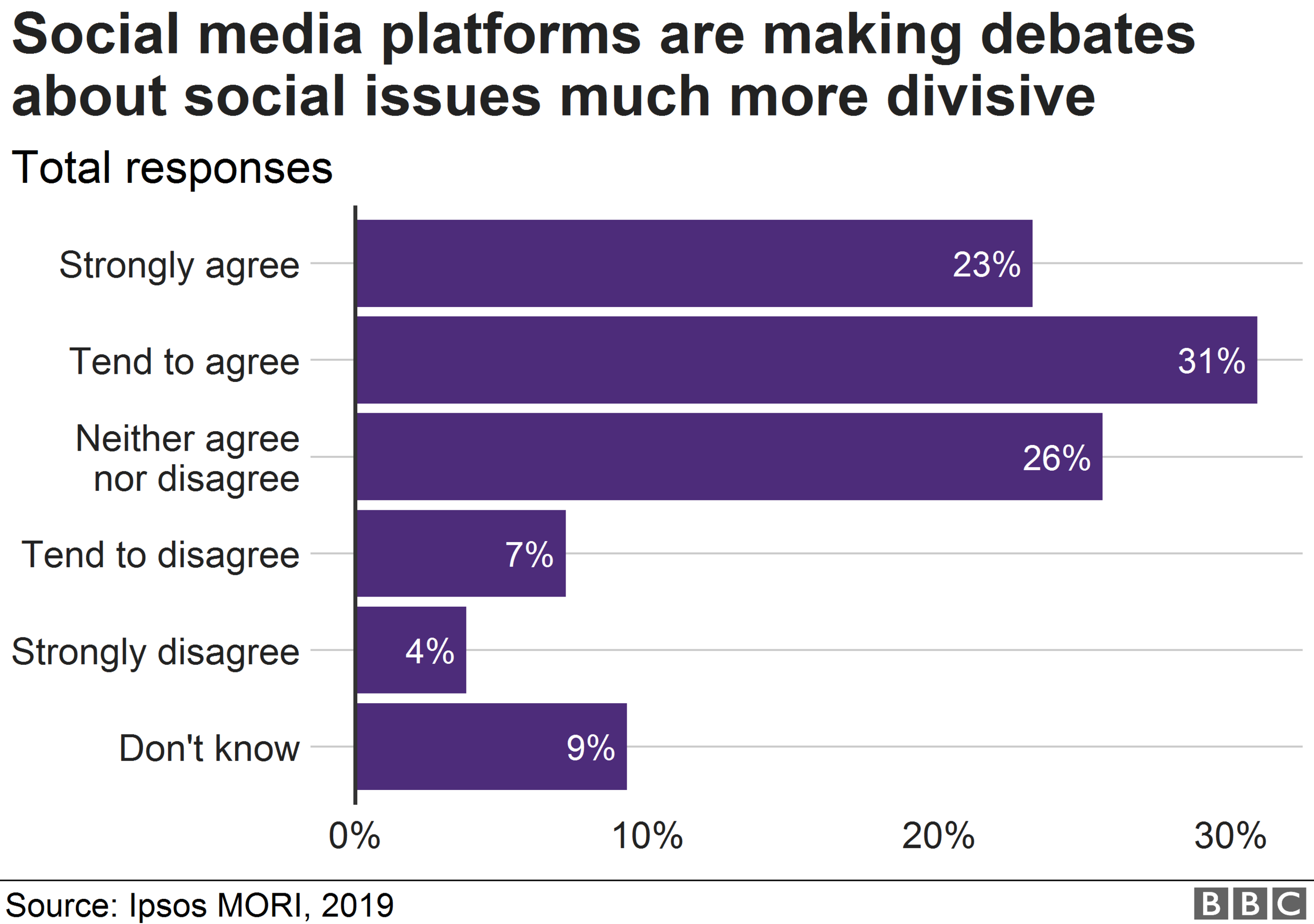

What about the effects of social media?

Boon or curse? Views are mixed.

While social media is helping to break down barriers and give a voice to many, the survey suggests a majority of people believe platforms such as Facebook and Twitter play a big part in polarising opinion.

And the limitations?

There are some limitations as to how much the research data can tell us about the real nature of the "social bubbles" people may be living in.

The Ipsos Mori study, conducted between November and December 2018, assessed people's perceptions of reality, as opposed to factual information. In other words, it shows us how diverse participants consider their friendship circles to be rather than how diverse they are.

Also, only people who had online access were surveyed.

As a result, in 15 of the 27 countries the sample was representative of the country's demographics, but in the remaining 12 the group polled was more urban, more educated and with higher incomes than the national average, so results cannot be extrapolated to the overall population.

Note on quiz methodology

The answers to each survey question are categorised according to where they fit on a spectrum between comparative isolation from people with different backgrounds and points of view to strong connections with them.

The result assigned at the end of the quiz is based on an aggregation of the position on the spectrum for each answer given, so people who click the most socially isolated answer for each question will end up in the "bubbling over" category, and those clicking the opposite answers will get "bubble free", with middling answers steering readers towards the corresponding middling categories.

But the categories at the end of the quiz are defined by the responses people gave to the survey, rather than any arbitrary definition of what it means to be in a social bubble.

So, if an answer corresponds to one end of the spectrum but was also a common response in the survey, then this will steer the reader towards the relevant category less than if it were an unusual survey response.

For example, when asked whether it was "important to listen to people who are different" from themselves, many people in the survey sample answered "very much" - in fact this was the most common answer. Therefore answering this way in the quiz would mean that a reader would still be heading towards the "bubble free" category, but to a lesser extent than the opposite answer ("not at all") would steer a reader towards the "bubbling over" category.

BBC Crossing Divides

A season of stories about bringing people together in a fragmented world.

- Published27 February 2019