What happens when an ambassador is summoned?

- Published

This is what the summoning of an ambassador might look like, in some imaginary reality

"The ambassador has been summoned."

It's one of those lines we might use every day here at the BBC, and it sounds serious. So our apologies if we've never explained what this actually means.

What does the process involve? What does it aim to achieve? Is it really that serious? We spoke to four summoned ambassadors to ask them.

John Casson - former UK ambassador to Egypt

In August 2015, three journalists from the al-Jazeera network were sentenced to jail in Egypt for "spreading false news". Outside court, Mr Casson spoke on Egyptian television in Arabic to condemn the sentence.

Soon after, Egypt's foreign ministry said it had summoned him to attend its offices. In doing so, it used one of the few diplomatic tools a host country has when it wants to make its anger felt to another country.

"I was called by the foreign ministry and was told 'We need to see you immediately,'" Mr Casson tells the BBC. "The first thing they said was, 'We are not summoning you, but we are going to tell the press we are summoning you. If it had been a summoning, we would have sent a formal diplomatic note summoning you.'"

This is the way things normally work in a summoning - a formal, polite, diplomatic note is sent to the relevant country's embassy asking - but not really demanding - its representative to attend a meeting at the foreign ministry, or its equivalent. The medium of the summoning is the message, Mr Casson says.

"The main thing is that it is a piece of diplomatic theatre and everybody understands their role, and acts their role," Mr Casson, who was in Cairo between 2014 and 2018, says. In London, the drama can involve being made to wait in the grand surroundings of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, to understand the seriousness of the occasion.

"The interesting question," Mr Casson asks, "is that if this is theatre, who is the audience?"

John Casson speaks to journalists after a plane crash in Sharm el-Sheikh in 2015

In this case, he says the audience was the Egyptian public, who needed to understand their government was fighting back against perceived foreign interference in their judicial system.

But summonings by themselves are unlikely to make the ambassador's country change its approach, Mr Casson says. "It isn't completely useless - it's a way of saying, 'Let's not build up a head of steam.' It's a symbol of serious political will but not on its own - it needs to be backed up by other stuff. It doesn't make the government think 'Crumbs'."

Ichiro Fujisaki - former Japanese ambassador to the US

Mr Fujisaki, a former Japanese ambassador to the United Nations, also served as its representative in Washington between 2008 and 2012.

In December 2009, he was summoned by US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. This was notable for two reasons: this is not something the US state department does often, and Japan is a close ally of the US, so an unlikely subject of a summoning. The Washington Post reports Mrs Clinton was "blunt, if diplomatic" with Mr Fujisaki.

"It was rather unusual," Mr Fujisaki says. "But I thought the American government wanted to convey their message rather rapidly."

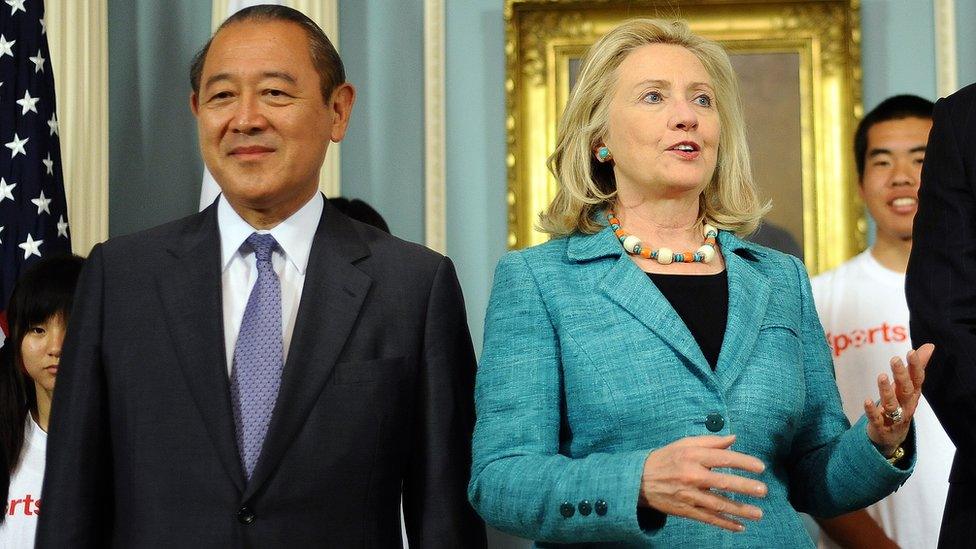

Ichiro Fujisaki with Hillary Clinton, two years after she summoned him (or maybe didn't summon him)

The message in question was about plans to move the US military base in Okinawa. There was just one problem: the new Japanese Prime Minister, Yukio Hatoyama, opposed details of the move. And so, Mr Fujisaki was called to the state department in the middle of a snowstorm, when all other government buildings were shut, to hear Mrs Clinton's view: the military base was being moved, end of story.

Although Mr Fujisaki was widely reported to have been summoned, he disputes the use of the word - and says no-one in the diplomatic service uses it. "A summoning sounds like you are obligated to be there, it's more legal," he says. "In this case, the government is asking you to be there, it's a request."

Mr Fujisaki says the ambassador must speak to his home government so that they do not learn of the summoning through the media. The home government would then brief the ambassador on the most appropriate way to respond and what points they should make.

Ambassadors can be summoned in inconvenient circumstances - as when Israel's foreign ministry called on 12 countries' representatives on 25 December 2016, external, when many were away for Christmas.

So was making Mr Fujisaki travel across a city in a snowstorm a way of inconveniencing him, and reinforcing the state department's unhappiness? He says not.

Peter Beckingham - former UK ambassador to the Philippines

Harry Enfield and Paul Whitehouse: the unlikely instigators of a diplomatic crisis

Mr Beckingham may be the only ambassador summoned by his hosts over a TV comedy sketch.

In 2008, the BBC show Harry and Paul featured a sketch in which one character encouraged another to "mount" a Filipina maid. The sketch caused outrage in the Philippines, external and was called "completely disgraceful" and "distasteful".

Cue the summoning by the Philippines Foreign Minister Alberto Romulo. "I knew him very well," says Mr Beckingham, who is now retired. "We had played golf on one occasion and we had been to each others' homes.

"I think he probably knew the BBC was an entirely separate organisation from the British government, but he felt he had to remonstrate about that item. It was an entirely civil conversation and I remember we spent a greater time talking about British history and politics, about which he knew a great deal.

"They then issued a pretty stern press release which I don't think entirely matched the conversation we had. But that was the point of the exercise - that they could say they had challenged the British government."

Ilir Bocka - Albania's ambassador to Serbia

Mr Bocka, the Albanian ambassador in Belgrade since 2014, is in an unusual position: he once refused a summoning by his host country.

Four months into his ambassadorship, Albania's football team travelled to Serbia for a Euro 2016 qualifying match. About 40 minutes in, the match was stopped when a drone flew overhead carrying an Albanian nationalist flag.

Perhaps the first time a drone has caused a diplomatic incident

A brawl broke out, and the match was abandoned. Soon afterwards, Mr Bocka received a demarche from Serbia's foreign ministry - a polite request for him to attend, rather than an order.

"This is the most common way diplomacy is done," Mr Bocka tells the BBC. "You are asked to go, normally to the director, and you have to hear what they have to say, and at the same time, you have the right to express your position."

A year later, it was a different story. Before the return match in Albania's capital Tirana, the Serbian team bus was pelted with stones and a window was cracked. Cue the summoning, and a cranking-up of diplomatic pressure.

"They asked me to go immediately to the foreign affairs ministry but I said no," Mr Bocka says. He did not feel the stoning of a bus merited his summoning. "I knew what had happened: nothing! It was 22:00, I said 'maybe tomorrow', but they wanted to have this story on the TV, so I said 'No, I'm not coming'. I told them I wouldn't play this game."

Mr Bocka acknowledges how rare it is for an ambassador to reject a summoning by his host country, and the refusal was not without consequences. For several months afterwards, he was disinvited from foreign affairs ministry events, even while his staff continued to work unhindered.

But he stayed in his job, and four years later, is on good terms with his hosts again. "Our relations were damaged for a moment," he says. "But now? It's OK."

Related topics

- Published18 July 2019

- Published10 July 2019