Six foreign policy issues the UK's new PM will face

- Published

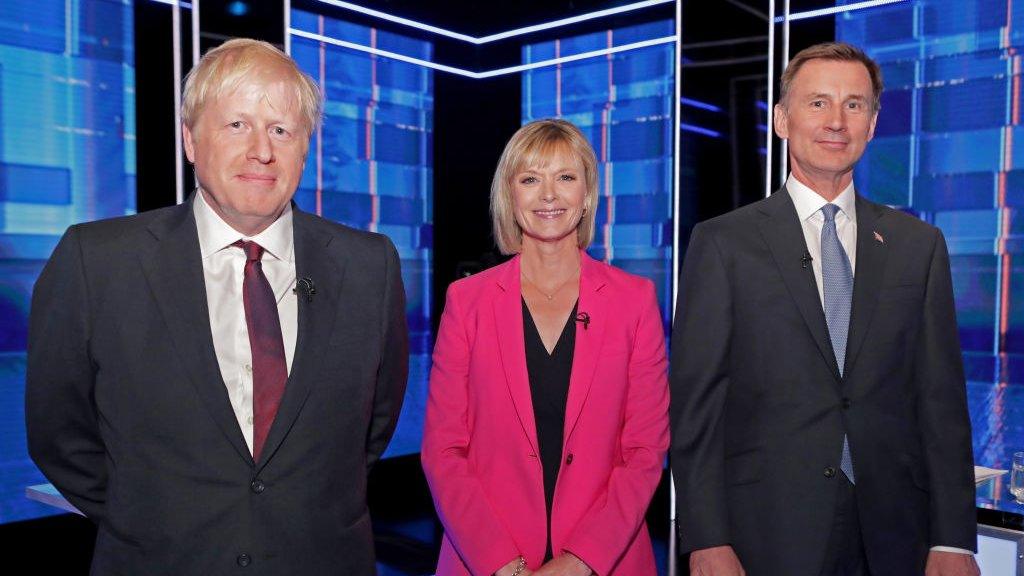

Boris Johnson and Jeremy Hunt are fighting to take over from Theresa May as the leader of the Conservative Party and the UK's next prime minister.

Central to the contest is an interpretation of what may or may not happen on 31 October, when Britain is scheduled to leave the European Union.

But whoever enters Downing Street will not only shape a fresh approach to Brexit, they will also have to make fundamental decisions about Britain's domestic and foreign policies that could have just as much significance in the years ahead as the immediate negotiations with the EU.

Both candidates have served as foreign secretary.

They should have a solid understanding of the international challenges facing the UK. But that doesn't mean either will necessarily have the right foreign policy to deal with them.

1. The United States

The first task will be to repair UK-US relations.

Both sides are bruised. The White House is still smarting from being described as inept and dysfunctional by former British ambassador Sir Kim Darroch in secret diplomatic cables leaked to a newspaper.

British officials are still furious at President Donald Trump's reaction, which declared Sir Kim all but persona non grata, effectively leaving him little choice but to resign after Mr Johnson chose not to support him in a TV debate.

The choice of Sir Kim's replacement will be key. Should the new prime minister cave in and allow Mr Trump to dictate who represents the UK in Washington in the hope that such acquiescence repairs the relationship and paves the way for a US trade deal?

Sir Kim Darroch resigned as the UK's ambassador to the US, following a leak of diplomatic cables

This might mean a political appointee, perhaps with overt Brexiteer credentials. Or should he stand firm, and show the kind of core political strength Mr Trump appears to respect, safe in the knowledge any trade deal will ultimately be shaped by Congress, not the White House?

That could point towards a career diplomat who would reassure Whitehall and steady the ship in Washington.

But this relationship is about more than diplomats - the new prime minister will also have to navigate some tough issues, such as China and Iran, where the UK takes a different approach to the US.

2. Europe

The new prime minister will also have a diplomatic repair job in Europe. However Brexit pans out, relationships across the Continent will need to be patched up.

The Foreign Office is already shifting resources from Asia and elsewhere to shore up its European missions, including an extra 50 new posts. And British diplomats recognise there will have to be a renewed focus on bilateral relations when the UK no longer shares the EU umbrella.

But the new prime minister will also have to address the UK's reputational damage. This is more than just the bemusement of allies at what they consider the loss of British pragmatism. In some capitals, there is outright hostility.

Prime Minister Theresa May and German Chancellor Angela Merkel

A German diplomat once explained why Boris Johnson was widely loathed across Europe. "It is because he compared the EU to Nazi Germany," he said.

"What we see as European values are the antithesis of Nazi values, in the same way they are the antithesis of the values of the East German Stasi, the Portuguese junta, Vichy France. I know you Brits don't do European values, you see it all as transactional and economic. But this is why [his] remarks are so offensive."

Mr Hunt also caused some upset when he compared the EU to the Soviet Union.

Reversing this hostility will take time and diplomatic effort, as the UK also tries to decide how it wishes to co-operate with the EU after Brexit.

Norwegian Prime Minister Erna Solberg has said she may support the UK rejoining the European Free Trade Association after Brexit if it wished

Britain will retain many shared strategic interests and will have to work out how to engage with EU structures.

Might it be worth talking to the Norwegians about how they lobby the EU from outside? What about the Swiss model? Should Britain try to sit as an observer on EU foreign, security and defence structures?

3. Iran

Iran is another key issue. Avoiding conflict in the Gulf will almost certainly be at the top of the new prime minister's to-do list.

In 2015, Iran agreed a long-term deal on its nuclear programme with a group of world powers known as the P5+1 - the US, UK, France, China, Russia and Germany

With the UK firmly in the European camp still backing the Iran nuclear deal, the new prime minister's attitude to the US will be crucial.

If, for example, Mr Johnson is in Downing Street and his warm relations with Donald Trump continue, might he be more easily tempted to adopt a more hostile approach to Iran? Some diplomats in Washington sense a shift in the UK's position already, although Whitehall officials deny it.

Either way, the UK and its fellow European signatories to the nuclear deal will face some tough choices if Iran breaches even more provisions of the agreement.

Tehran is already stockpiling more low enriched uranium nuclear fuel than is allowed.

It has also begun enriching uranium to levels just above limits permitted by the deal. What if it starts enriching weapons-grade uranium, as it has threatened to do unless Europe does more to help Iran's economy?

Will Britain bow to US and Israeli demands that the EU reimposes sanctions on Iran?

And what if there is some kind of open military clash between the US and Iran? What role might the UK play?

Iranian naval boats have already tried to impede one British tanker, forcing HMS Montrose to intervene. Future incidents might not end so peacefully.

Tensions in the region seem to be rising rather than falling and could escalate. Avoiding war will require deft diplomacy and Britain will have to play its part in that.

Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, pictured with her daughter Gabriella, is serving a five-year sentence in Iran for alleged spying

The new prime minister will also inherit the sadly unchanging case of Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, the British-Iranian national detained in Tehran. Both candidates know the issue well.

Mr Johnson was criticised for mishandling the case while at the Foreign Office. Mr Hunt has been punchier with Tehran. But neither has made any discernible progress. Current tensions may make progress even less likely.

4. China

The other pressing issue is China. The diplomatic dispute over the Hong Kong pro-democracy protests has clearly damaged UK-China relations. The Chinese have aimed robust language at British ministers, who pushed back, summoning China's ambassador for a dressing-down.

Hong Kong leader Carrie Lam has condemned the "extreme use of violence" by protesters

Britain's response has clearly been shaped by the leadership contest, with neither candidate wishing to sound conciliatory. But how to handle the growing economic and military power of China is one of the great geopolitical issues for any country in the 21st Century.

Is China a security risk or an economic opportunity? The new prime minister will not want the row over Hong Kong to determine that broader strategic decision.

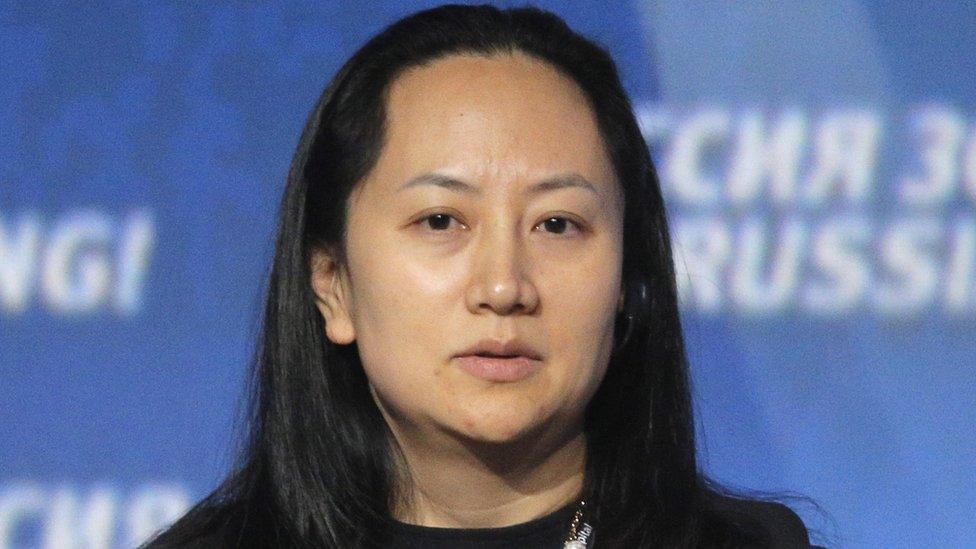

What should Britain do about Huawei, the telecoms giant the US and others fear is too close to the Chinese state?

The UK has to decide whether to allow the Chinese company to play any role in providing Britain's future 5G mobile phone network. Will the government compromise and allow Huawei to make what are called "non-core" parts of the network?

Huawei's chief financial officer, Meng Wanzhou, was arrested in Canada in December at the request of the US

This matters not just for technical and security reasons but because it has become symbolic of whether governments around the world see China as a threat or an opportunity.

The UK wants to see it as both - a fence-sitting that some see as incoherent - but the new prime minister will have to draw the line somewhere and that will require some nifty diplomacy, especially as the Trump White House sees China as a strategic opponent and wants all its allies to share that view too.

5. International rules-based order

More broadly, the new prime minister will also go out to bat on behalf of what is described as the international rules-based order - the post-War institutions and values that placed multilateral co-operation between groups of nations ahead of the crude nationalism that wrought so much damage to the 20th Century.

These bodies and ideas are being challenged by the populist power politics of leaders such as Donald Trump, who see international relations as bilateral and zero sum, meaning one country gains only at another's expense.

A British prime minister might place themselves at the head of a campaign to push back against the culture of strongmen politics

That campaign could be rhetorical, calling for change, but could also be practical, deploying political and diplomatic capital to ensure Britons are elected to key positions on international bodies.

Another urgent task will be a revamp of the government's beleaguered "Global Britain" strategy, external.

This was a slogan designed to convince people that Brexit did not mean a retreat from the world. But no-one has ever quite explained the policy behind the headline. At best, it was seen as wishy-washy internationalism - at worst, post-imperial nostalgia. So, it is ripe for a fresh approach.

The central calculation will be how honest to be about Britain's current status in the world before arguing for the real difference it can make diplomatically.

In the past, British politicians could talk with some justification of the UK "punching above its weight" through its membership of the EU and its relationship with the US.

That is harder these days and a canny prime minister may want find a new strategy that allows the UK to leverage its military and economic heft alongside the soft power of its language, legal system, universities, biotech and so on.

6. Whitehall

The final more domestic issue that needs addressing is the foreign policy structure the prime minister will inherit.

Growing voices are asking whether it really makes sense to divide the UK's international diplomatic effort between the Foreign Office, the departments for international development, international trade and exiting the European Union, and the National Security Council structure in the Cabinet Office.

Whom should the prime minister consult? His foreign secretary on policy? His international development secretary on aid money? His national security adviser on strategy? Is too much money spent on aid and not enough on diplomacy? Should more be spent on defence?

Mr Hunt has promised Tory members he would increase defence spending by £15bn over the next five years - a bold policy, as it is unfunded.

Mr Johnson has previously hinted he would support folding the Department for International Development back into the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. In February this year, he wrote a foreword to a Henry Jackson Society report calling for such a merger, which he described "a fantastic paper... full of good ideas".

Or could the FCO be given some control and oversight over all foreign-facing parts of Whitehall - the heart of the UK's government - in the same way the Treasury has a grip on all domestic-spending departments?

Prime ministers can be reluctant to rearrange Whitehall architecture - it rarely delivers the desired effect and always upsets the ministers whose chairs are being moved. But this change might be hard to resist.

So the new prime minister will have his diplomatic work cut out. That is, if he can find some time when he is not trying to sort out Brexit.

- Published10 July 2019

- Published9 July 2019

- Published23 July 2019

- Published2 July 2019

- Published23 June 2019

- Published25 February 2019

- Published11 July 2018