Letters to kids: Why it's a good time to write to your children

- Published

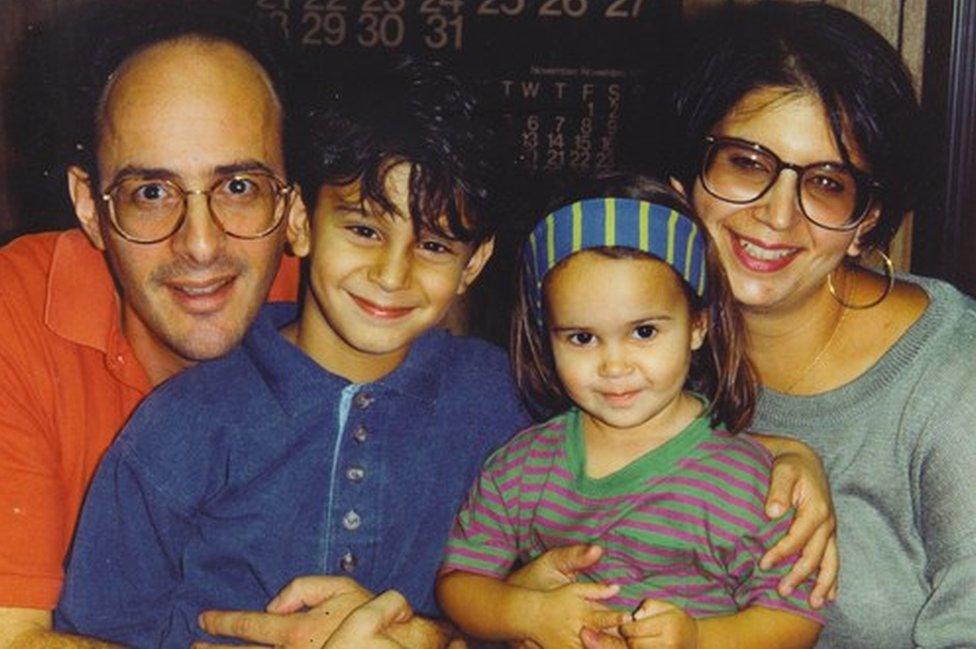

L-R: Diarist Bob Brody with his son Michael, daughter Caroline, and wife Elvira, pictured in 1995

The pandemic has presented many with an urge to express their feelings in writing. And for some that means passing on, in letters to their children, parts of themselves hitherto hidden from view.

"I think a lot of families faced the same quandary that I was running into - do my kids really know about my life? Maybe I should tell them while I still can. Because at some point it's gonna be too late." - Bob Brody

The pain and privations of this weird year have reshaped many families. From lost loved ones, to relationships frayed - or formed - in the intensity of lockdown.

Diary-writing has been booming, as a way to carve out mental space or clarify feelings while we grapple with instability. And if you've tried to explain the new world to children, perhaps it's left a sense that we're living through something worth recording. Something they'll understand better if we can pass our memories on.

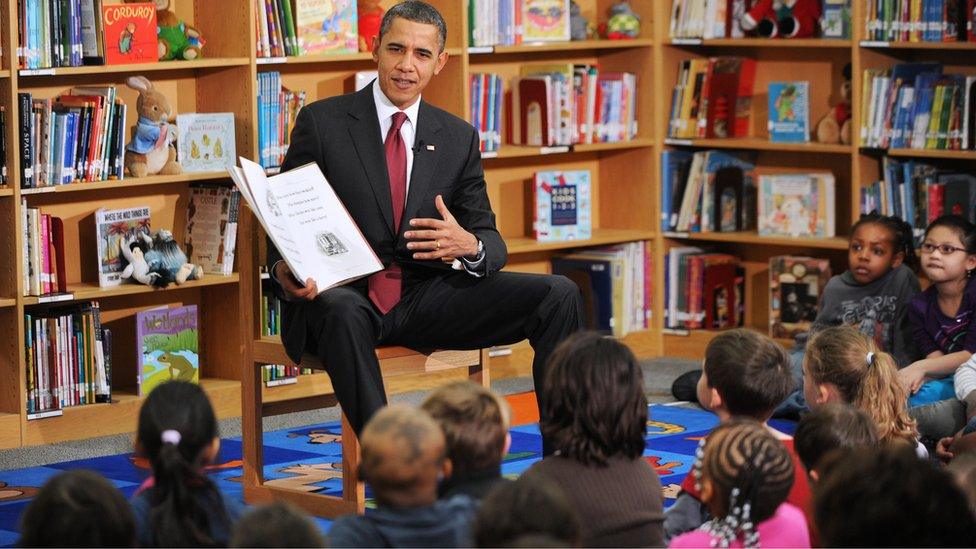

The literary history of parental letter-writing goes back to Ancient Rome, where the philosopher and statesman Cicero wrote a three-book essay to his son Marcus, outlining how to act with honour. More recently, Barack Obama released a picture book, Of Thee I Sing: A Letter to My Daughters, in 2010, during his first term as US president.

Barack Obama wrote a children's book inspired by his daughters

You don't have to be a politician or philosopher to record events or guidance for your children. Bob Brody, 68, is a New York-based consultant and essayist who felt that impulse more than a decade ago, long before Covid-19. He started a blog - Letters to my Kids - which became a movement of journal-keeping parents. Many of them wrote in stolen moments; coffee-fuelled on the train to work, or in half-conscious half-hours while a new baby slept.

"It happened as I entered my mid-50s," Bob says. "I just one day realised I had written all kinds of stuff for decades and decades, everything from articles to newsletters, brochures, stuff for newspapers and magazines, a book, two unpublished novels… some deeply misguided short stories… and somehow I had managed to do all this writing without aiming anything at the audience most important to me - namely my kids.

"All I could think was - how much do my kids know about me, how much do they know about my recollections of their childhood, how much do they know about my family - my parents and grandparents?

"Somehow we had never really found time to tell stories. Everybody was just busy doing stuff, living our lives."

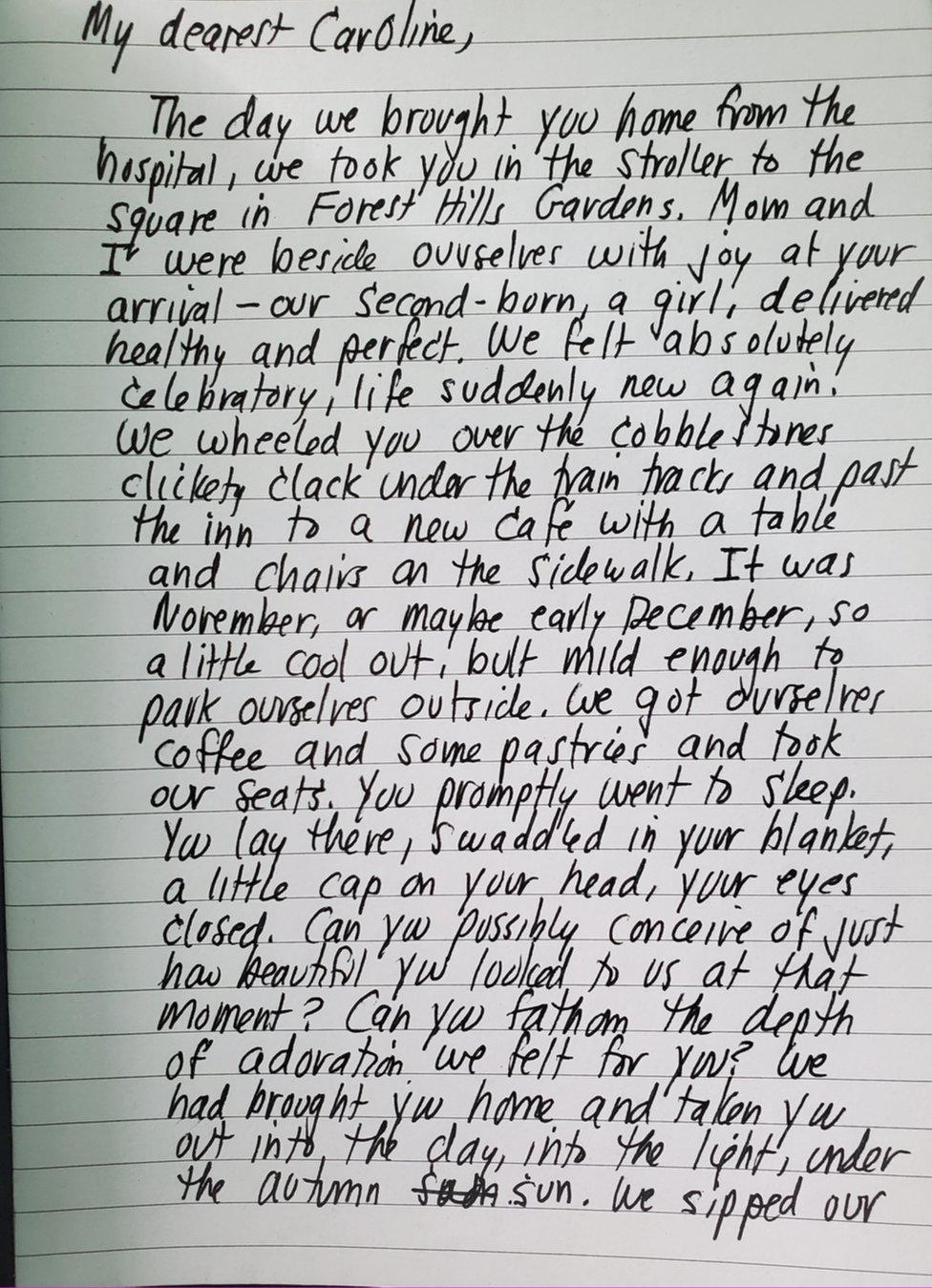

His children, Michael and Caroline, were 25 and 20 years old when the project started in 2008. It was a New Year's Resolution, and Bob set out the terms. He would write by hand, in journals, and they would take the form of letters addressed to his son or daughter. Nothing would be crossed out or rewritten, and he would try to capture moments - incidents, encounters, something Caroline said, something Michael did. One journal for each child.

Time - or the lack of - was a problem, so Bob committed to writing a few hundred words once a week, in secret, on Saturday or Sunday mornings.

He spent a year beavering away. "Then on Christmas Day we were all together, our family, and I said to the kids - I wrote something for you, Michael, and I wrote something for you, Caroline. And here you go."

Bob's children were already young adults when he decided to capture his memories of their childhoods

Bob had written the letters as an act of love and memory for his children, but also as a legacy - a repository of knowledge about the relatives who came before them.

"They told me they appreciated my honesty in talking about my own life, my parents, my career, and everything that came through about my feelings for my kids," he says. "And something that really stuck with me was - they told me they felt bad about some of the difficulties I'd gone through as a boy, particularly because both my parents were deaf. I think some of those recollections about trying to have a conversation with my mother, and my mother having trouble understanding me, brought my kids a certain sadness."

Bob ended up writing for a second year, figuring there was more he had to say and more the children wanted to know. Then on Fathers' Day 2010, with his family's tentative sign-off, he made the letters the basis for a blog and started encouraging people to write their own.

As well as his own letters and a how-to guide, Bob wanted to feature guest posts from other parents. One of those he asked was Lisa Sepulveda, a former colleague and friend of 30 years. At the time, he had no idea she'd been writing journals for her daughters for 18 years.

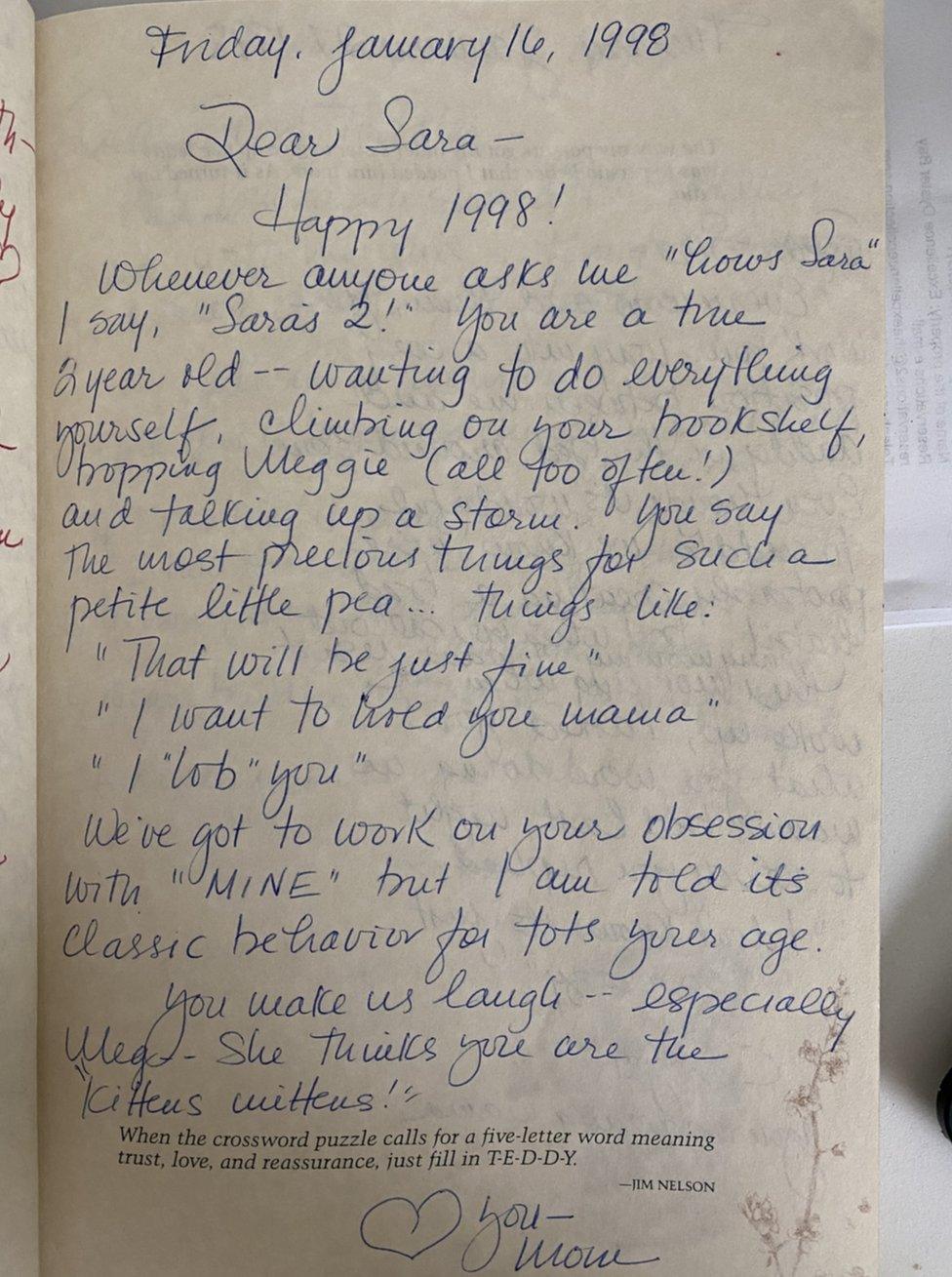

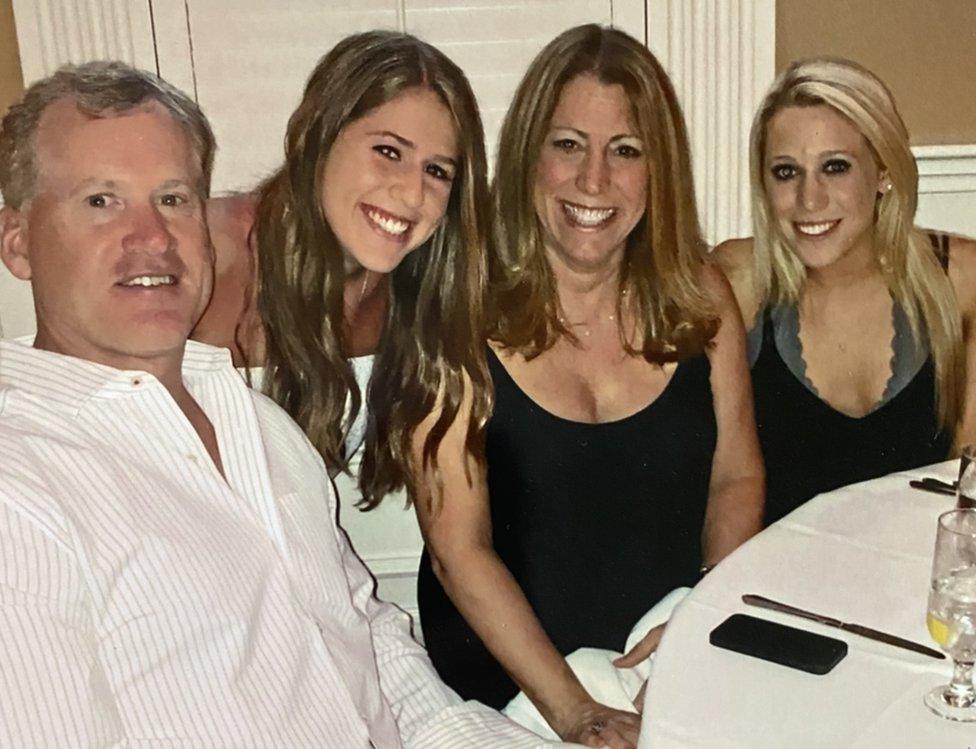

Lisa Sepulveda, pictured with her husband Andrew and daughters Sara (middle) and Megan, wrote journals for each of her children for more than 20 years

Now 56, Lisa is CCO of global clients at international PR firm Edelman. Her eldest child is Sara, 25, and Megan her younger daughter is 23.

She started penning letters to her daughters before they were born, with a deep sense of purpose drawn from the early loss of her own mother.

"When I was growing up my mom passed away when I was 19," she says. "She had leukaemia, she was sick. We were very close. And there are some scrapbooks, some photos. I cherish every one of those things that my mother had collected. What I realised after my mom passed away is that I didn't have all the answers to my questions. Some of them were really mundane, like when did I lose my first tooth, and things like that. So I had this burning desire to leave my daughters answers to as many questions as I could, for as long as I was here.

"And so I started the letters, and it went 'Dear Sara…'"

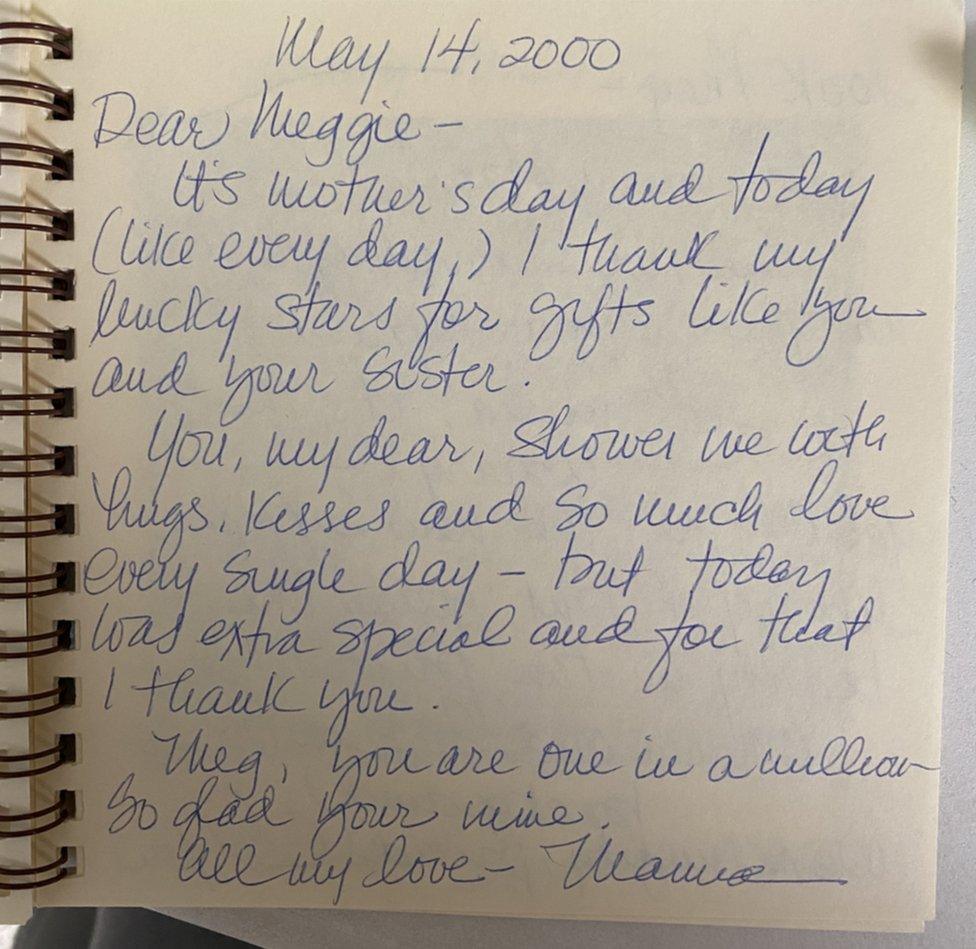

Lisa's journals included the things her girls said as toddlers - including the words they couldn't pronounce

Over the years, Lisa filled several journals for Sara and Megan, and decided she would pass them all on when the girls turned 21. She stored them in a steel box for maximum safe-keeping.

"I lovingly named Sara's The Sara Chronicles, and Megan's Letters to Megan. It was my favourite project, so it was going to be something that I did for as long as I could. But I also wanted [them to be] old enough to appreciate it.

"As they got older, I started adding some photographs, some articles of things that were happening in the world. I tried to keep it upbeat but I didn't want to hide that there's sadness in the world also. There was a couple of entries that I typed and put in each of their journals, and one of them was after 9/11, 'cos it was so hard to write it."

Then at 42, Lisa was diagnosed with breast cancer. Her daughters were 15 and 16 at the time.

"I had to write about that, because you couldn't ignore that moment, in the middle of telling them about their lives. That's another reason why I think the journals had to wait, for a moment that was happy, to be celebrated. But you couldn't only paint a rosy picture. You had to paint a picture that was real and true."

As her family grew up, Lisa found herself writing challenging journal entries on 9/11 and her breast cancer diagnosis

"There are small joys in this horrible time that we're living in, and you have to find them because it's what lifts you up. I think that people are using their time in different ways, and sometimes looking for more meaningful ways. I didn't start a journal or anything like that during the pandemic - but boy, it would be interesting for my girls' children to see."

It's clear her daughters feel the same.

Sara had this message for her mum: "The day I was handed those six journals I knew I was in for the most special journey. Who knew the story of my life would be such a page-turner? I am beyond lucky to cherish these handwritten journals you kept for me over the years - this will become a tradition we pass down from one generation to the next."

Megan also plans to write for her own children one day, adding: "Words cannot express how lucky I feel to have a mom so thoughtful and dedicated to these memory books."

Lisa admits that friends would say to her "How do you find time? You must have 27 hours in your day. You're making me feel guilty." But over the years, many have taken up their pens for special family occasions, or committed to one journal entry a week.

"I think I have motivated a lot of my friends to either start, do it for their grandchildren - it's never too late to write a letter," she says. "It's never too late."

If at this point you're thinking you'd love to record your memories for your kids, but writing doesn't come easy to you, sociologist Dr Michael Ward has some excellent advice - try another medium.

Dr Ward, a Senior Lecturer in Social Sciences at Swansea University, has been collecting submissions for a sociological study about lockdown life - the Corona Diaries - since mid-March.

"I kind of hoped for about a dozen people," he smiles. "I've ended up with 178 participants between the ages of 11 and 89, from 12 different countries."

Diary entries of all kinds are welcome, and importantly, submissions don't have to be written: "There's a range of other virtual media things," says Dr Ward. "Videos, memes, TikToks, YouTube videos, artwork, we're talking paintings, sculptures… One person sent me a radio show that they did for local radio: fourteen nights' dinner with the host. Somebody kept a dream log. One participant's mother who was doing some cross-stitch said, 'Ooh, can I contribute my corona cross-stitch to the project?' And she did."

The Corona Diaries will ultimately go into an online archive at Swansea University, to help illustrate and illuminate the pandemic in years to come.

Corona Diaries contributor Ellie Griffiths: "We're in a very big part of history right now"

Yet writing, and other forms of memory-keeping, can compound pain as well as joy - and Covid-19 has brought trauma and loss into many people's lives this year.

"We have to remember that some people find writing about chaotic events quite triggering," Dr Ward says. "So writing and recording your thoughts and feelings isn't always productive because it can set you back into a difficult mental space."

On that basis, letter-writing isn't something anyone owes to children, no matter what you live through or how much you love them. It's vital to look after your mental health.

But if you are in the right headspace, and what's holding you back is lack of confidence, Bob Brody has a parting word of encouragement.

"I understand that a lot of people are uncomfortable with writing," he says. "I think people should do it anyway. Sometimes non-writers can pull off something like this even better than a writer might. They're not trying to be literary.

"A lot of people know how to tell stories. And everybody has stories to tell. I would just say to people: Tell your story. And tell it to your kids. Who better to tell it to?"

Related topics

- Published14 April 2020

- Published27 May 2020

- Published26 September 2016

- Published30 January 2019