European peace seems as fragile as ever

- Published

WWII Soviet propaganda poster depicting hoped-for victory over the Nazis - which Putin constantly references

There are moments when the tectonic plates of history shift beneath our feet and Europe is violently remade. It is time to recognise that we are at such a moment. Time too, to stop saying that it is somehow unbelievable that this can be happening in 2022.

It is no more unbelievable now than it was in 1914 or 1939 - nothing predetermined that they would be years when darkness would descend. That's not to say, of course, that we are on the edge of a war that will suck in the rest of Europe or even the world.

The point is that peace is always fragile - and that what happens even in the most distant corners of Europe will always affect all of us.

Drawing the right lessons from those big moments when everything changes is not easy.

The French military commander Ferdinand Foch called the end of World War One a "20-year" ceasefire - because he felt the victorious allies had overplayed their hand in dealing with the defeated German Empire. He was about a year out.

Ferdinand Foch circa 1914

The question for our generation is whether or not we made a similar miscalculation over how to handle Russia when the Soviet Union collapsed. We rejoiced as Poland, the Baltic States and others took their place among the free nations of the world.

Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic - once occupied by Soviets - joined Nato in 1999. The Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia followed five years later.

But the dark energy that drives Vladimir Putin is the other side of that coin. He saw Russia diminished, humiliated and stripped of what he saw as its right to a buffer zone of subordinate states.

He illustrates the point with a story - which might even be true - from his own shadowy past. A former colonel in the counter-intelligence corps of the KGB, Putin was reduced to acting as a part-time taxi driver. One imagines he would have been rather a difficult one.

At some point he conceived an almost mystical concept of restoring lost Russian greatness. He must have been encouraged by the way in which he got away with the annexation of Crimea - from Ukraine - in 2014. After all, four years later we were enjoying the World Cup in Russia.

Western Europe's main reaction to the end of the Cold War was to take a 30-year holiday from serious defence spending.

Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev announced the Soviet Union's dissolution and his resignation on 25 December 1991

At one point a few years ago, only four of Germany's 128 fighter aircraft were combat ready and the Dutch had a plan to dispose of every one of their heavy tanks. The Dutch have thought again and the Germans are now proposing to spend an extra €100bn (£83bn) on defence.

It is good of course that Germany reflects on its past, but it's even better that it is thinking of the future too.

The German Chancellor Olaf Scholz is a Social Democrat who certainly didn't run for office on a promise of raising defence spending but he has risen to the historical demands of the moment rather impressively.

"With the invasion of Ukraine we are in a new era," he told the German parliament - defining the challenge of that new era as a simple question: "Whether we allow Putin to turn back the clock, or whether we mobilise power to set boundaries for warmongers such as Putin."

They are extraordinary words from the leader of a country where politicians once argued that the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941 made it impossible to stand up to the Kremlin.

A Ukrainian soldier with rocket launchers in Kyiv

Sweden, which is wealthy and well-armed but militarily non-aligned, was the first country to feel colder winds blowing from the East and perhaps the first to act. It is increasing defence spending by an extraordinary 40% in its current five-year cycle - raising new infantry regiments and buying American Patriot anti-aircraft missiles.

The Swedish Defence Minister Peter Hultqvist said simply: " We have a situation where Russia is prepared to use military means to achieve political goals."

So the rather decadent view - that the only weapon the West would ever need is economic sanctions - is out of fashion now. You can't fight tanks with banks. No-one wants to see this continent turned into an armed camp of course, but when you feel those tectonic plates shifting you have to shift with them. Acting now - buying weapons and donating money - is the easy bit when the hot sharp stab of outrage is fresh.

But this new age of containment is going to call for much more. The will to stand with Ukrainians first - but then the grit, vision and staying power to stand guard over freedom wherever and whenever the next attack might come.

Russia attacks Ukraine: More coverage

THE BASICS: Why is Putin invading Ukraine?

SCENARIOS: Five ways the war in Ukraine might end

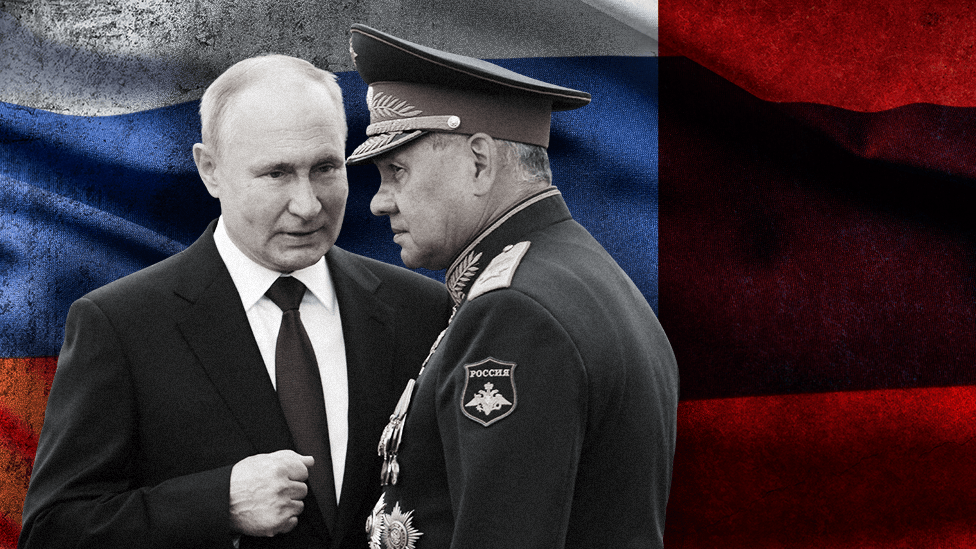

INNER CIRCLE: Who's in Putin's entourage, running the war?

IN DEPTH: Full coverage of the conflict

- Published24 June 2023

- Published3 March 2022

- Published3 March 2022