Sri Lanka: Why is the country in an economic crisis?

- Published

The International Monetary Fund is lending Sri Lanka $3bn (£2.4bn) to help it deal with its worst economic crisis in its history as an independent nation.

Soaring prices, shortages of essential goods and crippling international debts sparked nationwide protests last year which caused the president to flee the country.

What has been happening in Sri Lanka?

In early 2022, Sri Lankans started experiencing power cuts and shortages of basics such as fuel. The rate of inflation rose to 50% a year.

As a result, protests broke out in the capital Colombo in April that year and spread across the country.

The country ran short of fuel for essential services such as buses, trains and medical vehicles because it did not have enough reserves of foreign currency to import any more.

The fuel shortage caused petrol and diesel prices to rise dramatically.

In June last year, the government banned the sale of petrol and diesel for non-essential vehicles for two weeks. Sales of fuel remain severely restricted.

Schools had to close, and people were asked to work from home to help conserve supplies.

What happens when a country runs out of money?

Sri Lanka has been unable to buy goods it needs from abroad.

And in May 2022 it failed to make an interest payment on its foreign debt for the first time in its history.

Long queues for fuel - like this one in Colombo - have made normal life impossible

This damaged its reputation with lenders, making it even harder to borrow money on the international markets.

What's the plan to tackle the crisis?

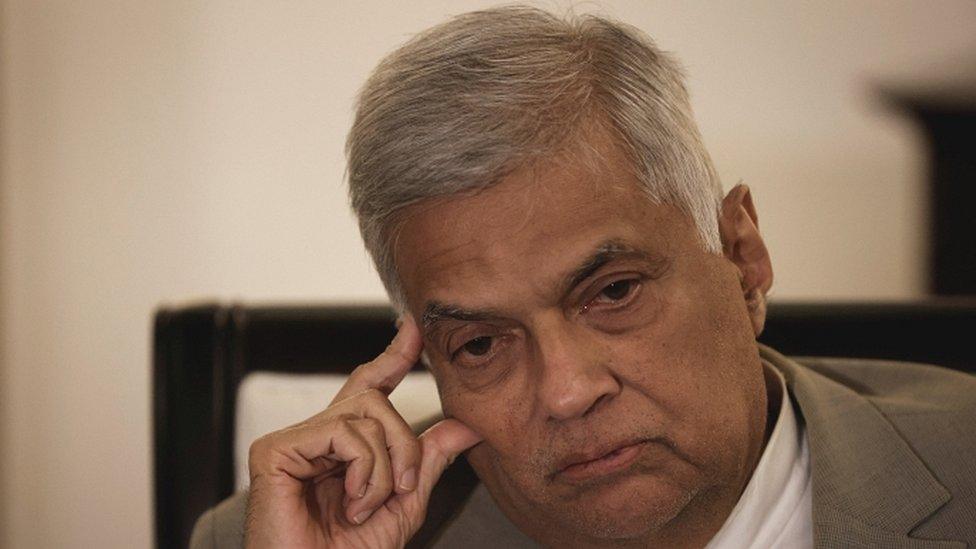

In the face of massive protests, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa resigned in June last year. Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe became acting president and declared a nationwide state of emergency across the country.

Mr Wickremesinghe has been prime minister six times, without seeing out a full term in office

The mass protests have subsided, but the new president is trying to deal with a huge financial crisis.

Sri Lanka owes about $7bn (£5.7bn) to China and around $1bn to India.

Last month, both these countries agreed to restructure their loans, giving Sri Lanka more time to repay them.

Thanks to this, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has agreed to lend Sri Lanka $3bn. That is on top of a $600m loan that the World Bank made last year.

Sri Lanka's government says it will raise funds to repay its debts by restructuring state-owned enterprises and privatising the national airline.

Banging dishes together to protest at the food price hikes.

In early 2023 the country introduced income taxes for higher earners, ranging from 12.5% to more than 36%.

It also raised other taxes to pay for critical purchases, including fuel and food.

What led to the economic crisis?

The government blamed the Covid pandemic, which badly affected Sri Lanka's tourist trade - one of its biggest foreign currency earners.

It also said tourists were frightened off by a series of deadly bomb attacks in 2019.

However, many experts blame Mr Rajapaksa's economic policies.

Mr Rajapaksa's departure ends a family dynasty that has dominated Sri Lanka's politics for the past two decades

At the end of its civil war in 2009, Sri Lanka chose to focus on providing goods to its domestic market, instead of trying to boost foreign trade.

This meant its income from exports to other countries remained low, while the bill for imports kept growing.

Sri Lanka now imports $3bn more than it exports every year, and that is why it ran out of foreign currency.

At the end of 2019, Sri Lanka had $7.6bn in foreign currency reserves, which have dropped to around $250m.

Mr Rajapaksa also introduced big tax cuts in 2019, which lost the government more than $1.4bn a year in revenues.

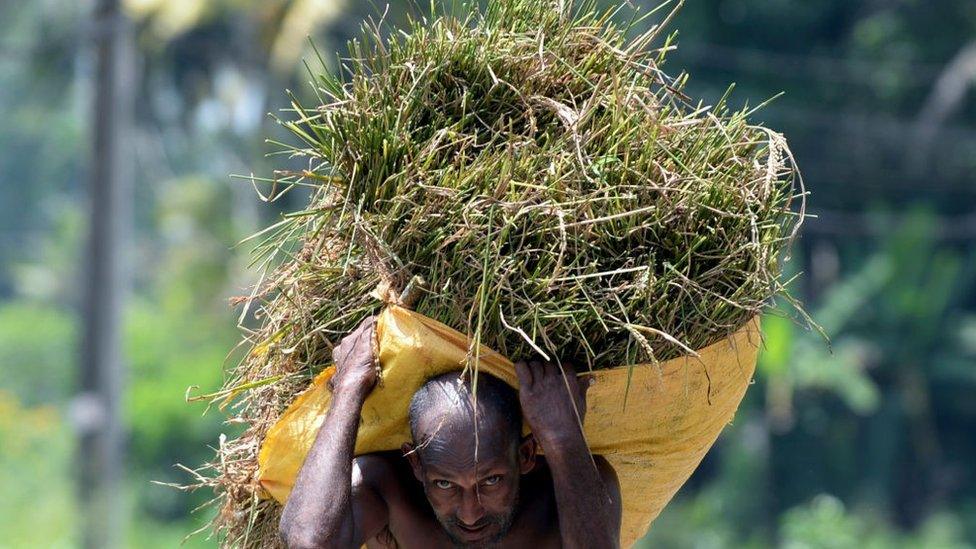

The switch to organic fertilisers resulted in widespread crop failure, exacerbating foreign currency shortages

When Sri Lanka's foreign currency shortages became a serious problem in early 2021, its government tried to tackle the issue by banning imports of chemical fertilisers.

It told farmers to use locally sourced organic fertilisers, instead.

This led to widespread crop failures. Sri Lanka had to supplement its food stocks from abroad, which made its foreign currency shortage even worse.