Australia radioactive capsule: Missing material more common than you think

- Published

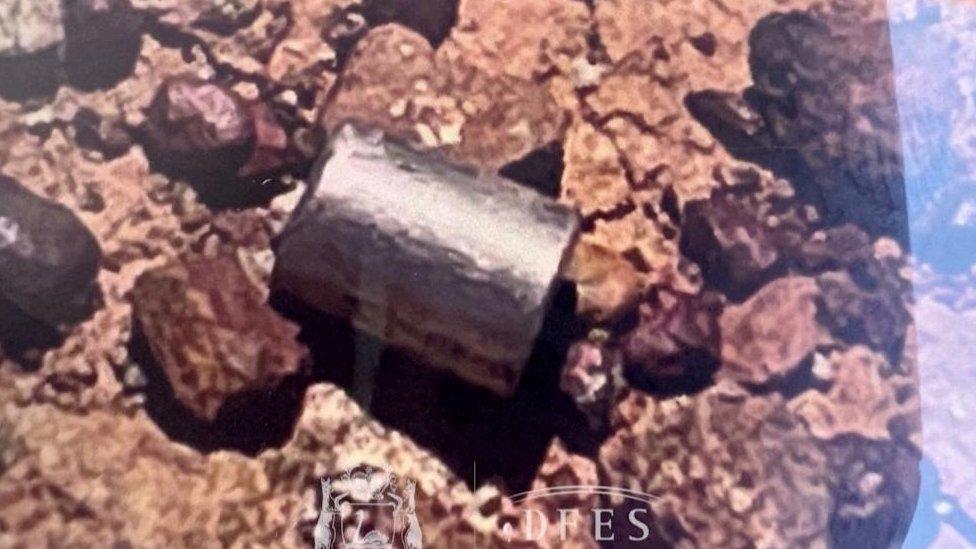

The world watched as Australia scrambled to find a radioactive capsule in late January.

Many asked how it could have been lost - but radioactive material goes missing more often than you might think.

In 2021, one "orphan source" - self-contained radioactive material - went missing every three days, according to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

The not-for-profit Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI) lists lost and found nuclear and radiological material, external, and its records include a person in Idaho who stumbled across a radioactive gauge lying in the middle of a road.

The organisation also listed a package containing radioactive material falling off the back of a truck onto a nearby lawn in an undisclosed location - the resident who found it then delivered it to its intended recipient later that day.

And, in 2019, a tourist was detected in St Petersburg airport wearing a radioactive watch, according to the list.

Of the nearly 4,000 radioactive sources that have gone missing since the International Atomic Energy Agency started tracking them in 1993, external, 8% are believed to have been taken for malicious reasons, and 65% were lost accidentally. It is unclear what happened to the rest.

When properly maintained and handled, radioactive material does not pose a significant threat to humans.

But if a person is directly exposed to the radiation without protection, they can fall severely ill - or even die.

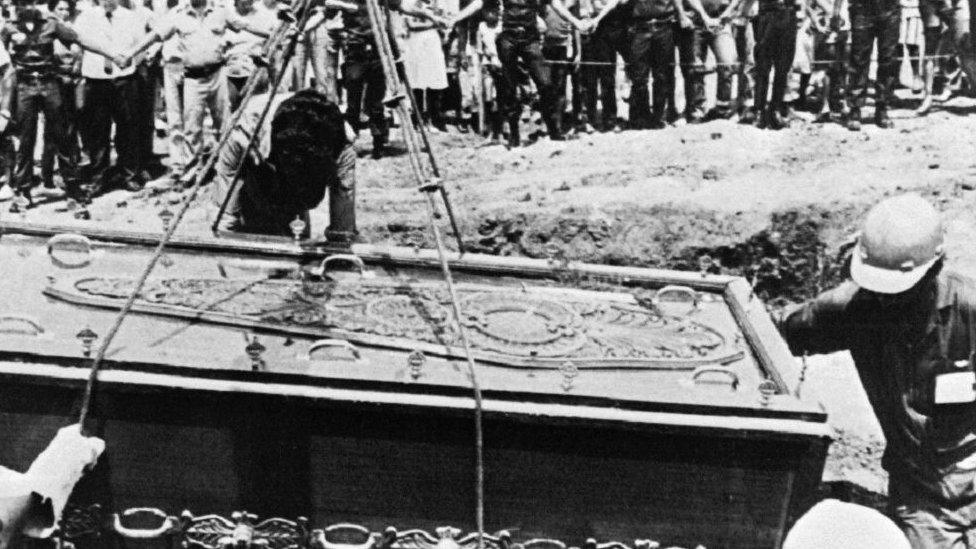

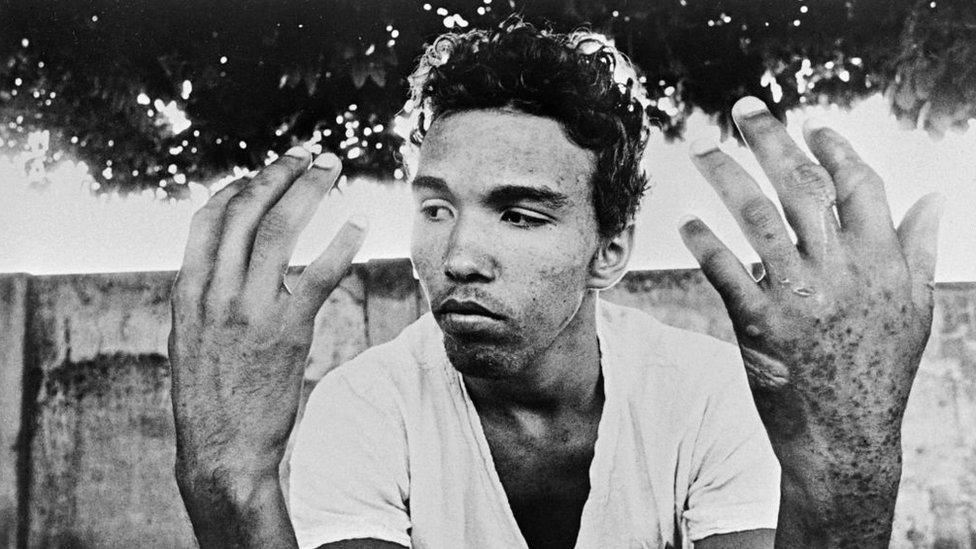

Four people died in the Goiania nuclear incident

For example, four people died after a canister containing radioactive material was stolen from an abandoned hospital in the Brazilian city of Goiânia in 1987.

A group of men took the canister that contained Caesium-137 (Cs-137) - a radioactive material commonly used in medical settings - thinking it may have some value as scrap metal. As they took it apart, they ruptured the Cs-137 capsule, spilling its radioactive contents onto the rest of the metal.

A junkyard owner who bought the contaminated metal then exposed dozens of friends and family to the radiation after he brought them to see it glow blue in the dark. This included a six-year-old who ate the radioactive powder.

Dozens required urgent medical attention and two nearby towns were evacuated once doctors established their sudden illness was caused by radiation exposure.

The incident was described by the IAEA as among "the most serious radiological accidents to have occurred".

In 2020, radioactive waste was also found at the home of a former nuclear energy agency employee, external in Indonesia.

And in 2013, six men were arrested - apparently unharmed - in Mexico for stealing radioactive material from a cancer treatment machine.

Why is radioactive material so prevalent?

When the Australian nuclear capsule went missing, many questioned why it was there in the first place.

But radioactive materials are commonly used for a variety of purposes.

Medicine relies heavily on radioactive material to treat millions of cancer patients worldwide, for heart scans and to diagnose diseases.

And radioactive material is found in household objects. Americium-241, an isotope that emits alpha and gamma radiation as it decays, is found in homes around the world in an unassuming device: a fire alarm.

When 66 smoke detectors were lost in southern Ontario, Canada, in 2019, they were listed as missing radioactive material, according to NTI.

The number of radioactive objects that are successfully transported every year - around 15 million - well outweighs the number that go missing, according to World Nuclear Association's Jonathan Cobb.

Dr Cobb told the BBC that the transport of any radioactive item is "closely regulated", but noted that it did not excuse radioactive capsules being misplaced - including the recently lost capsule in Australia.

"It should not have happened. Let's make that absolutely clear from the start."

Dr Cobb added that, when regulations are followed and nuclear items are properly maintained, they do not pose a significant threat.

And while the amount of attention the missing Australian capsule received was unusual, Dr Cobb said he hoped that more people may recognise what a radioactive capsule looks like - and keep clear.

Related topics

- Published30 January 2023

- Published1 February 2023