Kenyan referendum vote brings out fruity colours

- Published

The "yes" and "no" camps have been out in colourful attire for the campaign

After plenty of failed efforts over the past two decades, it is once again decision time in Kenya: a new constitution or the status quo?

The current constitution was negotiated with the British at Lancaster House back in the early 1960s.

The new constitution aims to limit the power of the president, make politicians far more accountable and generally clean up the extremely dirty world that is Kenyan politics.

At the final "yes" campaign rally before the 4 August vote, the mood was celebratory.

Thousands of men, and a few women, wore green - the colour indicating approval for the new constitution.

'Watermelons'

Although the polls point to a green victory, this race could be very tight.

The red rallies have also attracted large crowds and significant opposition to the land clauses in the proposed document.

The "no" campaign has been gathering momentum

You could be mistaken for thinking that Kenyans were obsessed by fruit.

At the last constitutional referendum in 2005, the two sides had oranges and bananas as their symbols. When someone said, "the bananas are saying they are far from happy", you briefly wondered what kind of imagination the Kenyans had.

In this vote, you need to look out for the watermelons - the term for politicians who currently back the new constitution, but who are, in fact, against it and will work to uphold the status quo even if it is passed.

They may be green on the outside, but they are red on the inside.

And perhaps the true red colour of the watermelons will soon be revealed.

These days the political elite is seen as virtually untouchable.

Corruption scandals come and go, ministers under the spotlight are often briefly taken out of the beam only to return to another top job.

There are those who believe the status quo suits a very powerful, very wealthy, influential clique of Kenyans very well.

'Choppy waters'

John Githongo of the Kenyan grassroots organisation, Inuka, says that if the constitution passes, it will be the start of "one of the most dramatic regroupings of conservative forces in Kenyan society... a regrouping of conservative forces in the political class, bureaucratic class, in the security sector, and in the business community that will be very formidable".

"It is something we have got to be prepared for and therefore there are choppy waters ahead, but they are choppy waters heading in the right direction, rather than heading backwards," adds the former anti-corruption chief.

"They will do everything they can to monkey-wrench implementation of the new constitution. August 4th is merely the start of the process but we can expect it to be a challenging one."

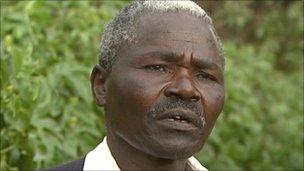

Farmer Daniel Kogei says he is worried about new land rules

That is if the new constitution is approved.

The "no" campaign has gained momentum in recent weeks and has garnered support around the controversial land issue.

Outside the town of Eldoret I met Daniel Kogei on his six-acre farm.

It has been home to his family for generations and he hopes to pass the land on to his seven children and grandchildren.

"I will vote no," he tells me beside a crop of passion fruit.

"I have a right to a big piece of land or a small plot as long as it was obtained legally.

"But my worry is the land commission based in Nairobi might make up new rules and take away the land," he said, referring to the commission which the new constitution would see set up.

These fears are common here in the fertile Rift Valley, which has seen an influx of non-Kalenjin tribes, and on the coast which has also been targeted by many as prime land.

Land enrichment

But Atieno Ndomo, a policy analyst, suggests that those fears which are spreading around small farmers are being "blown out of proportion" by politicians.

She says that land has traditionally been held as an "instrument of unjust enrichment and as an instrument of corruption where just one man - the president - has the power to decide who gets what land and what to do with it".

"Any of the reports into land misuse confirm that people who have unjustly enriched themselves from land are the people who are also very close to power," she adds.

She said that those who have spoken out most about the land clauses are those who have acquired land "in very unfair and unclear ways" and are therefore worried about what will happen to it.

Whatever the outcome of the referendum, the issue of land will be difficult to address without increasing divisions.

That will not be easy as politicians have in the past used the issue to ramp up tension when it suited them.

'New trajectory'

Many Kenyans on both sides of the red-green divide agree the new constitution is not perfect, but such a document will always need compromise.

Although the polls point to a green victory, the race could be very tight

The reformists see it as a potentially significant step forward for Kenya.

"The signal getting this passed will send for our country and our people is the idea that you can actually resolve to make a change and get it to happen - that's not to say everything is going to change immediately, but we are starting a journey that perhaps is going to redefine the path that we are following as a nation," said Ms Ndomo.

"That's really important and one couldn't downplay the significance of that shift - this is an opportunity to choose a different trajectory for Kenya," Ms Ndomo added.

Considering that Kenyans were suffering under oppressive one party rule not so long ago, the inclusive nature of a referendum is progress.

If the process passes off peacefully, Kenya can then also show the world it has turned a corner and moved on from the days when voting meant violence.

- Published26 July 2010

- Published15 June 2010

- Published13 June 2010