Is Kenya finally getting tough on corruption?

- Published

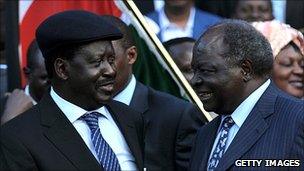

Raila Odinga (l) and Mwai Kibaki have campaigned together in the past on an anti-corruption platform

Two Kenyan ministers, the capital's mayor and a technocrat in the key ministry of foreign affairs have resigned within the last two weeks, raising hopes that the government has finally come to terms with the corruption that blights Kenya's economy and the lives of its citizens.

After prevaricating for years, President Mwai Kibaki and Prime Minister Raila Odinga have suddenly made war against graft a key pillar of their leadership.

At every recent public gathering, the two coalition government principals have upped their ante against the scourge, warning government officials and Kenyans in general that they will crack the whip.

Surveys show that Kenya, generally seen as one of Africa's more stable and prosperous countries, is also one of its most corrupt.

The most recent corruption perception index from watchdog Transparency International (TI) shows Kenya placed a joint 154th, along with war-torn nations or those recovering from conflict such as Congo, Cambodia and Guinea Bissau.

Kenya was placed lower than Zimbabwe (134) under Robert Mugabe and crisis-prone Madagascar (123).

Citizens' arrests

The first to resign was Higher Education Minister William Ruto. He is charged with defrauding a state corporation of $1.2m (£750,000) nine years ago over the sale of forest land.

A week later, Foreign Affairs Minister Moses Wetangula and his Permanent Secretary Thuita Mwangi followed him out of government for their role in the purchase of diplomatic properties in Nigeria, Egypt, Pakistan and Japan.

And, a day later, Nairobi Mayor Geoffrey Majiwa had to step aside after he was charged in court over the city council's acquisition of cemetery land for $3.8m (£2.3m).

All four have vehemently denied being involved in corruption.

In 2002, when Mr Kibaki and Mr Odinga campaigned together under the National Rainbow Coalition and subsequently formed the government in January 2003 they were elected on an anti-graft platform.

So enthusiastic were Kenyans about fighting corruption that they enforced citizens' arrests and nabbed police officers who dared take bribes from motorists.

But the zeal soon petered out with the unearthing of the Anglo Leasing scandal just one year into President Kibaki's first term.

Since then, the case has remained an albatross around his neck. The government is feared to have lost an estimated $750m (£467m) in the case, entering into contracts with phantom companies and purchasing over-priced services and equipment.

But following the violence after the 2007 election and the formation of a coalition government between Mr Kibaki's Party of National Unity and Mr Odinga's Orange Democratic Movement, fate seems to have re-united the two leaders again.

Robust

The new constitution and the appointment of Patrick Lumumba as the new anti-graft tsar at the Kenya Anti-Corruption Commission (KACC), external has given the battle a new impetus.

Indeed, all the resignations have come since the new constitution was passed in August.

Despite relatively stable government since independence, Kenya is perceived as highly corrupt

There now seems to be a serious commitment to tackling the vice that has dogged governments since independence.

Parliament has equally become aggressive, flexing its muscles by probing suspicious government deals.

Technocrats and ministers have been summoned by various committees of parliament to explain their expenditure, recruitment and choice of state corporation chiefs, much to the chagrin of the executive.

Mr Odinga himself has complained that the legislature was interfering so much with the work of the executive that some technocrats were reluctant to make decisions and government projects were being delayed.

The new set of laws has robust clauses which call for any public servant named in any corruption case to step aside until they are cleared by the courts or the anti-corruption institutions.

But, in a country where everything is seen through political and ethnic lenses, the fight against corruption is likely to run into trouble.

All talk?

Following the resignation of the four officials, more accusations have been levelled against key ministers on both sides of the political divide.

While the KACC has said it has its eyes trained on more senior officials, politicians have been competing to show one part of the ruling coalition as more corrupt than the other.

Moses Wetangula says his hands are clean

Moses Wetangula (October 2010)

Long before the new constitution, several ministers and top government officials had been mentioned in corruption deals but the president and prime minister always turned a blind eye.

The investigations into the subsidized maize scandal which cost the government an estimated $40m and the pilfering of petroleum by the Triton Company to the tune of $102m, are for example, yet to be resolved.

Kenyans and the international community will be watching with interest to see how the two political principals handle the recent cases which caused the resignations in government.

So despite all the talk, Kenyans are still waiting for proof that concrete action is now being taken to stop the corrupt profiting from their crimes.

Under Mr Kibaki, no politician has been sacked or charged for corruption.

Five ministers implicated in the Anglo Leasing and the Goldenberg scandals were asked to step aside only to be re-appointed and moved to different ministries after pressure on the government had eased.

Previously, ministers implicated in corruption have blamed technocrats.

All the technocrats named in the Anglo Leasing scandal were off-loaded by Mr Kibaki's regime.

- Published27 August 2010