Kenya's new constitution sparks hopes of rebirth

- Published

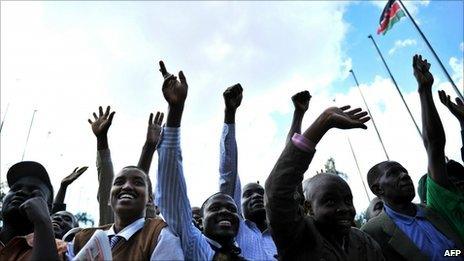

Supporters of the new constitution say it brings much-needed changes

With a single flourish of his pen, Kenya's President Mwai Kibaki changed Kenya forever.

Moments after he signed the new constitution into law and held the document aloft before the cheering crowds, canons broke into a 21-gun salute, and a military band began playing the national anthem.

It was an appropriately grand moment to herald the birth of what the nation's political leaders are hailing as "the birth of the second republic".

And there is plenty to celebrate.

The debate over a new constitution began 20 years ago, then surged and receded with each national crisis. Finally, a referendum early this month approved the proposed document.

Through it all was a recognition that something fundamental had to change if Kenya was ever going to escape the repeated rounds of ethnic blood-letting that came with each election.

The fact that the troubles only emerged around election time was the clue to the problem.

It was not that there is anything inherently incompatible about the tribes; it was the way the original constitution encouraged politicians to exploit tribal differences.

Corruption 'rife'

The president was all-powerful; he was able to make appointments without parliamentary oversight.

Previous presidents were able to create a bloated cabinet filled with parliamentarians who owed them favours.

There was no clear separation between the government and the judiciary. The system of provincial government encouraged tribal competition for jobs and money. Corruption was rife, and accountability almost non-existent.

And land - an issue that lies at the very heart of tribal identity - was carved up and parcelled out as a way of manipulating electoral numbers and returning political favours.

Kenyans spent hours queuing to cast their votes in the referendum

Political analyst Kwamchetsi Mokhoke believes this new constitution tackles all those issues and more.

"It's a new experiment in which we are trying to create a nation that runs on the competition of ideas and individuals rather than forcing people to coalesce around ethnicities in order to defend their interests".

This is not just a tinkering at the edges of the way the country is designed.

The authors of the new document have utterly transformed the way power is distributed and managed.

The most significant changes include:

Parliamentary oversight of most presidential appointments and decisions

Constitutional limits on the number of cabinet posts

A senate to review parliamentary decisions

Powerful provincial governments replaced by a network of smaller counties

The creation of a Judicial Service Commission

A citizens' Bill of Rights

A land commission to return stolen property and review past abuses

All of those changes, in their own way, add checks and balances to the centres of power, and undermine tribal politics.

'Opened our minds'

The Kikuyus who live in the Pipeline camp for displaced people know about tribalism.

All 1,250 families who live in the squalid plastic tent city outside the Rift Valley town of Nakuru fled there to escape their neighbours after the elections of 2007.

Even now, almost three years later, they cannot go back. Yet people, like camp chairman Paul Thiongo, are surprisingly optimistic.

"Kenyans have now opened their minds," he said.

"They know what they are doing now. Not like before. They were being told things by their leaders and they were following them without question.

"Now we know our rights. And that's why I think everything will change."

Even so, a sceptical shadow still hangs over the celebrations.

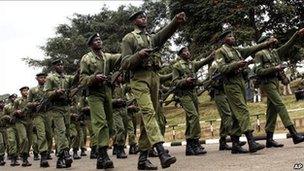

Kenyan military have been rehearsing for the ratification ceremony

Austin Ajowi also experienced some of the worst of the bloodshed in the notorious Mathare Valley slum in Nairobi.

There, it was not only rival ethnic groups who were killing one another - the police got involved as well.

He organises football tournaments on a sloping, pitted and dusty square of reclaimed land, as a way of healing some of the rifts within his community.

"I think there will be some changes. But to me, I think the real changes will only come when the leaders also want to change," he said.

And asked about whether he thought the nation's politicians were ready for change, all he could do was shrug.

Still, there is a sense perhaps born of hope more than confidence, that something profound is about to happen in Kenya.

But the nation that is about to be reborn is far wiser than the one that emerged at independence almost half a century ago.

- Published4 August 2010

- Published3 August 2010

- Published26 July 2010