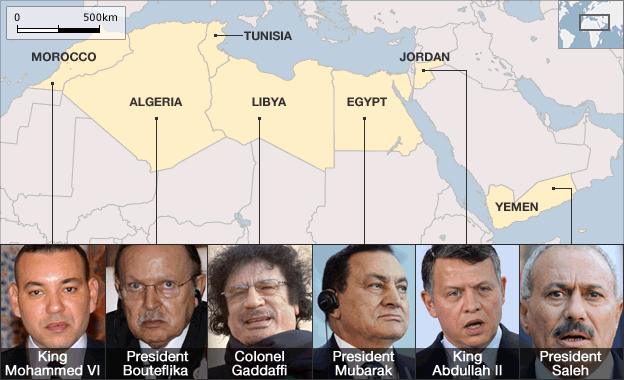

Mid-East: Will there be a domino effect?

- Published

Events in Tunisia and Egypt have sent shock waves throughout the Arab region

The Arab world has been transfixed by the recent dramatic events in Egypt and Tunisia. Popular street protests have swept across Egypt just days after similar protests saw Tunisia's President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali flee his country. Could a domino effect sweep more leaders from power as it did around Eastern Europe in 1989?

Egypt

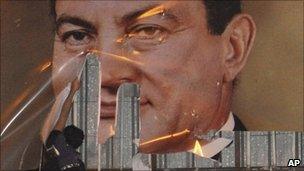

Rocked by more than a week of protests, Egypt's reputation for strength and stability has been swept away. Open defiance of the authorities and calls for President Hosni Mubarak to stand down forced a pledge from him to step aside at elections due later this year. However, he has resisted calls for him to go now and while the protests have continued, it is not clear who will prevail.

Protesters are demanding the president steps down

As in Tunisia, Egyptians face tough economic conditions, official corruption and little opportunity to express their dissatisfaction with the political system.

On 25 January, protesters called for a day of a "day of revolt" that drew thousands to central Cairo and other cities across Egypt in numbers not seen since the bread riots of the 1970s. The police response, using water cannon and rubber bullets, backfired. In the days of violent clashes that followed, some 300 people have died and hundreds more injured.

Many analysts say the strength of the protests means that real change in Egypt is now inevitable, but what that change will be is uncertain.

The US has called for an "orderly transition" to a more democratic system. Western powers fear that a power vacuum and the resulting chaos might allow armed Islamist groups to thrive.

In any free and fair election, the Islamist and conservative Muslim Brotherhood would be expected to do well. But questions remain as to whether it can reconcile its aim of creating a state ruled by Islamic law with democratic principles. And, if in government, how would it change Egypt's relations with the US and Israel?

Yemen

Following several days of protest, Yemen's President Ali Abdullah Saleh announced on 2 February that, after three decades in power, he would not seek another term in office.

Anger on the streets of Sanaa

He also told parliament that he would not hand over power to his son, saying: "No extension, no inheritance, no resetting the clock." His concessions came a day before planned mass opposition rallies across the country. Mr Saleh called on opposition groups to end their protests, but activists rejected his pleas and say they will go ahead with a so-called day of rage.

Unrest has grown since Tunisia's revolt in January. On 27 January, tens of thousands of Yemenis demonstrated in the capital Sanaa calling on him to quit. Mr Saleh attempted to head off unrest on 23 January by ordering a 50% cut in income tax and control of basic commodity prices.

The government also released 36 people jailed for participating in the unrest, including the prominent human rights activist, Tawakul Karman. At the same time, the president increased the salaries of state employees and armed forces personnel - a step apparently meant to ensure their loyalty.

Yemen is the Arab world's most impoverished nation, where nearly half of the population lives on less than $2 a day.

Algeria

As the winter protests escalated in Tunisia, its western neighbour also saw large numbers of young people taking to the streets. As in Tunisia, the trigger appeared to be economic grievances - in particular sharp increases in the price of food.

Unemployment and high prices have sparked demonstrations in Algiers

A state of emergency has been in place in Algeria since 1992, and public demonstrations in the capital are banned. Regular protests have occurred elsewhere in the country, but in recent weeks these broke out simultaneously across Algeria for the first time, including in the capital, Algiers.

Protests have not escalated in the same way as in Tunisia however. Analysts say the relatively restrained response of the security forces, as well as the government's intervention to limit price rises has kept things calmer.

Algeria's government has considerable wealth from its oil and gas exports and is trying to tackle social and economic complaints with a huge public spending programme. But grievances remain, including anger over unemployment, corruption, bureaucracy, and a lack of political reform.

Algeria's tumultuous recent history stands in stark contrast to Tunisia's. In the 1990s Algerian politics was dominated by the struggle involving the military and Islamist militants. In 1992 a general election won by an Islamist party was annulled, heralding a bloody civil war in which more than 150,000 people were slaughtered.

Syria

Syrian President Bashar al-Assad inherited power in 2000, after three decades of rule by his father, Hafez al-Assad. In January, he told the Wall Street Journal that Syria was more stable than Tunisia and Egypt and that there was no chance of a political upheaval.

However, some Syrian activists have turned to Facebook, calling for a "day of rage" on Saturday. Although the site is officially blocked, people routinely get around the restrictions. The activists are calling for peaceful protests against Syria's "monarchy, corruption and tyranny".

Like Egypt, Syria is ruled through emergency law and suffers from high poverty and unemployment. Since taking over from his father 11 years ago, President Assad has slowly opened up the economy, but political and personal freedoms are severely curtailed. There are thousands of political prisoners in Syrian jails, and major opposition groups are banned. The administration also blocks access to several internet sites and maintains a tight control on the media. And in a country where the Baath party has ruled for almost half a century, critics say cronyism and corruption are rife.

Libya

After 41 years in power, Col Muammar Gaddafi is the longest serving ruler in Africa and the Middle East, and also one of the most autocratic.

Reacting to the overthrow of Tunisia's President Ben Ali, he said: "There is none better than Zine to govern Tunisia. Tunisia now lives in fear."

Protest of any kind in Libya is strictly prohibited, but there have been reports of unrest in the city of al-Bayda.

The government also recently announced increased spending on public housing in a bid to head off growing disquiet.

Jordan

In the wake of large protests across the country, King Abdullah dismissed his government on 1 February and ordered new Prime Minister Marouf Bakhit to carry out political reforms.

Like other states in the region, there is anger against poverty and unemployment, and protesters have demanded that the prime minister be directly elected.

Jordan's powerful Islamic opposition movement, the Islamist Action Front (IAF), said it was not seeking to oust King Abdullah but added it did not welcome Mr Bakhit's appointment.

Jordan is run by its royal family and some sections of society are loyal to the monarchy. King Abdullah himself appears so far to have escaped most of the wrath of the protesters.

Morocco

Like Tunisia, Morocco has been facing economic problems and allegations of corruption in ruling circles.

Morocco's reputation was damaged after Wikileaks revealed allegations of increased corruption, in particular the royal family's business affairs and the "appalling greed" of people close to King Mohammed VI.

Wikileaks cables from the US embassy in Tunis had cited similar problems in President Ben Ali's inner circle.

But Morocco, like Egypt and Algeria, does allow limited freedom of expression and has so far been able to contain protests.

Like Jordan it is a monarchy with strong support among sections of the public.

- Published15 January 2011