Obituary: Muammar Gaddafi

- Published

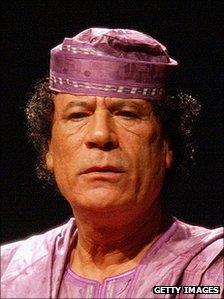

Muammar Gaddafi was a ruthless political operator

Muammar Gaddafi saw himself as a revolutionary whose destiny was to unite the many diverse elements of the Arab world.

In the first two decades of his rule Libya became the world's pariah, as the flamboyant colonel used his country's oil wealth to support groups such as the Irish Republican Army and the Palestine Liberation Organisation.

Western enmity towards Libya reached a peak in 1988 when Pan Am Flight 103 exploded over Scotland killing 270 people. It would be 15 years before Libya admitted responsibility.

Eventually it was his own people, helped by Western military effort who rose up and finally removed him from power.

Muammar Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi was born into a Bedouin family on 7 June 1942, near the Libyan city of Sirte.

As a teenager, he became an admirer of the Egyptian leader, Gamal Abdel Nasser, whose brand of Arab Nationalism struck a chord with the young Gaddafi.

He first hatched plans to topple the monarchy of King Idris, while at military college, and received further army training in Britain.

As Captain Gaddafi, he returned to the Libyan city of Benghazi and, on 1 Sep 1969, launched a bloodless coup while the king was receiving medical treatment in Turkey.

Gaddafi became chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council which was set up to run the country - one of his first acts was to expel his country's Italian population.

Arab nationalist

Like Nasser, he did not promote himself to the rank of General, as is the custom of most military dictators, but remained a Colonel throughout his rule. This fitted in with his idea of Libya being "ruled by the people".

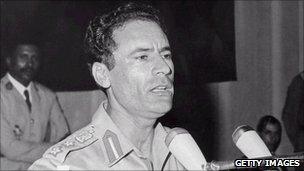

Gaddafi toppled King Idris and seized power in 1969

He laid out his political philosophy in the 1970s in his Green Book, which charted a home-grown alternative to both socialism and capitalism, combined with aspects of Islam.

His rule blended Arab nationalism with a socialist welfare state and popular democracy, although the democracy did not allow for any challenge to his own position as leader.

While small business were allowed to remain in private hands, the state ran the big organisations, including the oil industry.

No-one doubted that he exercised total control, and was ruthless in dealing with anyone who stepped out of line and opposed him.

Gaddafi believed in a union of Arab states and set out to extend Libya's influence throughout the region.

Repression

He began by trying to merge Libya with Egypt and Syria but disagreement over the conditions rendered it impossible. A similar arrangement with Tunisia also floundered.

Gaddafi's strong support for the Palestine Liberation Organisation also harmed his relations with Egypt which had reached a peace deal with Israel.

He sent Libyan forces into the neighbouring country of Chad in 1973 in order to occupy the disputed Aouzou Strip. Eventually this led to a full-scale Libyan invasion and a war that only ended in 1987.

In 1977 he invented a system called the "Jamahiriya" or "state of the masses", in which power is meant to be held by thousands of "peoples' committees".

His committees called for the assassination of Libyan dissidents living abroad and, during the 1980s, sent hit squads to murder them.

Gaddafi's regime was accused of serious human rights abuses

Libya had a law forbidding group activity based on a political ideology opposed to Gaddafi's revolution.

Campaign group Human Rights Watch claimed the regime has imprisoned hundreds of people and sentenced some to death. Torture and disappearances have also been reported.

Lockerbie

By the early 1980s Gaddafi's support for a diverse collection of revolutionary groups brought him into conflict with the West

The UK broke off relations with Libya in 1984, after the killing of Police Constable Yvonne Fletcher outside the Libyan Embassy in London.

Lockerbie was a turning point in relations with the West

Two years later, the United States bombed Tripoli and Benghazi as a reprisal for alleged Libyan involvement in the bombing of a Berlin nightclub used by American military personnel.

Libya was reportedly a major financier of the "Black September" Palestinian group that was responsible, among others, for the kidnap and killing of Israeli athletes at the 1972 Munich Olympics, as well as becoming a supplier of weapons to the IRA.

The Lockerbie bombing eventually triggered a change in the relationship between Gaddafi's regime and the west, although it was 11 years before Gaddafi agreed to hand over the two Libyan nationals who had been indicted for the crime.

Anxious for foreign investment as the price of oil fell, Gaddafi renounced terrorism. A compensation deal for the families of the Lockerbie victims was agreed and UN sanctions on Libya were lifted.

Months later, Gaddafi's regime abandoned efforts to develop weapons of mass destruction, triggering a fuller rapprochement with the West.

American sanctions were also lifted and Libya was reported to be helping western intelligence services in their fight against al-Qaeda

Civil unrest

In a climate of rapprochement, then UK Prime Minister Tony Blair went to Libya to meet Gaddafi in a Bedouin tent on the outskirts of Tripoli in 2004.

However, some in the West questioned this new relationship. And in parts of the Arab world, Gaddafi was criticised for cosying up to his old adversaries.

Gaddafi's forces ruthlessly suppressed opposition protests in February 2011

Gaddafi's eccentricity was legendary: He had a bodyguard of woman soldiers, and an almost narcissistic interest in his wardrobe. On one occasion reporters called to a news conference found him ploughing a field.

A tent was also used to receive visitors in Libya, where Gaddafi sat through meetings or interviews swishing the air with a horsehair or palm leaf fly-swatter.

There was also growing unrest among ordinary Libyans who claimed reforms were slow in coming and said they were not benefiting from Libya's wealth. Many public services remained poor and corruption was rife.

That unrest boiled over in 2011 when, spurred on by the toppling of Egypt's President Hosni Mubarak, and Tunisia's Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali, demonstrators took to the streets demanding the end of the Gaddafi regime.

Security forces, including African mercenaries hired by Gaddafi, clashed with anti-government protesters with reports the Libyan air force jets had bombed opposition areas. Hundreds of people were reported to have been killed.

This prompted the UN Security Council to authorise the use of force and Nato countries immediately started bombing loyalist positions.

Gradually, with Nato help, the rag-tag opposition forces advanced across the country, seized the capital, Tripoli, in August and set up a transitional government.

Gaddafi remained at large until 20 October, when he was finally located and killed in his home town of Sirte.

After all his bluster and bravado the longest serving leader in both Africa and the Arab world met an ignominious end.