Could South Africa's freedom fighters return to the streets?

- Published

Young South Africans were vital in toppling the apartheid government

Freedom fighters in South Africa who risked their lives fighting white minority rule say the African National Congress (ANC) government is neglecting them.

Fire burns in Farid Ferhelst's eyes as he speaks about his life today.

"I am angry and very disappointed in this government. Many of us have nothing to show for our pain," he says.

Many thousands of veterans who were involved in the liberation movement in the 1970s had hoped to be rewarded for their hard work - but almost two decades later they are living in poverty.

Many are also struggling with psychological trauma, drugs and alcohol while some have joined gangs, according to the Struggle Veterans Action Committee, which represents some 36,000 freedom fighters.

Mr Ferhelst was 14 when he helped to form the Bonteheuwel Military Wing (BMW), an underground youth group which was active in the Western Cape in the 1980s.

"Today many of our freedom fighters have no real life to speak of. Many of us didn't learn any skills apart from the ones we used during our warfare," he says.

He accuses the ANC of failing hundreds of thousands of "street fighters" - people who fought the apartheid security forces without formal military training and those who did not join the political parties.

Like many other underground movements in South Africa, members of the BMW group have gone without the benefits promised to veterans, such as healthcare and a pension fund.

Faizel Moosa, a former senior member of the ANC's armed wing Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) in the Western Cape, has described this as an "insult" and says it could lead to unrest.

"We don't want a situation where we end up as another Zimbabwe but the mood is certainly there," says the man who now heads the Struggle Veterans Action Committee.

"Our people are tired of promises and we are headed for a situation where people will just forcefully take what they want," Mr Moosa warns.

Mr Ferhelst agrees: "The government is forgetting that the same people who feel neglected and marginalised now are the same people who set the townships on fire in the 80s and brought the apartheid government to its knees."

Analysts point to President Robert Mugabe's decision to offer huge unbudgeted pay-outs to Zimbabwe's war veterans in 1997 - after they had protested at being "ignored" - as a key factor in the start of that country's economic collapse.

Economic collapse

Some have warned that South Africa may find itself in a similar situation if it blindly gives in to the demands of the veterans.

But they cannot be ignored either, argues the Military Veterans Department which was set up when President Jacob Zuma came to power in 2009.

They have been credited with Mr Zuma's victory in the 2007 ANC party leadership elections, which led to him becoming president.

But the freedom fighters are an increasingly fractious constituency in the ANC.

The cabinet last year approved the Military Veterans Bill, which seeks to provide a wide range of benefits for veterans including healthcare, housing, transport and pension.

The Veterans Department, which drafted the bill, says providing these benefits would cost South Africa around 20 billion rand ($2.9bn; £1.8bn) over five years.

This estimate has been questioned, with some saying it could cost as much as three times as much if all 56,000 registered veterans qualify for the benefits or if more veterans come to light.

Some opposition parties have questioned whether the state could afford such a high bill as it emerges from recession following the global economic crisis.

What about us?

Veterans who were not part of MK have also condemned the widespread belief that only the Umkhonto we Sizwe was involved in ending apartheid.

About 100 people were killed in the 1976 Soweto riots

"The ANC-led government have over the years given the impression that only its veterans freed South Africa. It continues to show preference to ANC freedom fighters when handing out state funds," says Mr Moosa.

But the Defence Department has denied this, saying it is in the process of compiling information on the country's anti-apartheid veterans with the aim of assisting everyone who qualifies for government aid, regardless of which party they served under.

Some communities in the Western Cape see the ANC as only benefiting a handful of elite and politically connected people.

Armien Sydow, a former commander of the underground forces, says he is angered by reports of corruption in government.

"Our people are not stupid, they are not blind. How are we supposed to feel when we see politicians getting rich through corrupt means while we who freed this country watch and starve?" he says.

The price of freedom

Mr Ferhelst - who has been in and out of therapy - says he is still haunted by the past.

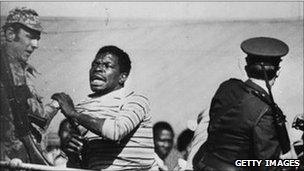

War veterans are blamed for sparking Zimbabwe's economic collapse

He was one of hundreds who testified in the 1996 Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) hearings.

During his testimony in 1996 he said he was captured and tortured by security police whenever there was unrest in the township - this lasted for a period of two years.

"I still carry a lot of pain and anger inside me. It's not easy to forget what happened to me," he tells me.

He and some of his colleagues are undergoing trauma counselling through the Institute of Healing of Memories (IHOM) in Cape Town.

IHOM says the sessions help the ex-combatants cope with the past and ease their re-integration into society.

But the veterans say they also need material help.

Townships in Cape Town, unlike Johannesburg's Soweto which is becoming increasingly middle class, tell a story of neglect and great poverty.

Rusty shacks line many streets, sewage overflows from drains, scores of people sit on streets corners whiling away time due to unemployment.

Once more some of these men - not so young any more - could be ready to take to the streets to demand improvements in their poverty-stricken lives.

- Published9 July 2024