Is Algeria immune from the Arab spring?

- Published

The Algerian government is working to prevent North Africa's revolutionary tide from reaching its shores. Political analyst Hamoud Salhi considers for the BBC's Focus on Africa magazine its chance of success.

For months now, Algerian authorities have been busy pre-empting a potential threat of revolution.

The success of popular movements in neighbouring Tunisia and Egypt sent alarming signals to government circles that Algeria was next in line to experience revolutionary change.

The effect has been so strong that local governments in the eastern part of Algeria have instructed police to relax street regulations, including allowing motorists to drive without a proper vehicle tax document.

Police have also been told to ignore illegal street traders and refrain from collecting taxes from shopkeepers if they claim their business has been affected by the activities of such traders.

So far the policy of appeasement and concession has worked well for the Algerian government. But for how long?

There are severe housing shortages in Algeria, accompanied by high consumer prices and low salaries. According to the International Monetary Fund, unemployment rates have reached 25% among 24 year olds, widening gaps between social classes.

Large revenues generated from favourably high prices of oil have enabled the government to divert people's anger and win their silence - at least for now.

Pleasing the people

The Algerian government, led by President Abdelaziz Bouteflika, has embarked on a series of initiatives to win over the public.

In early May, the government revised this year's national budget, allocating 25% of the total to pay for public sector workers' salaries and subsidies on flour, milk, cooking oil and sugar.

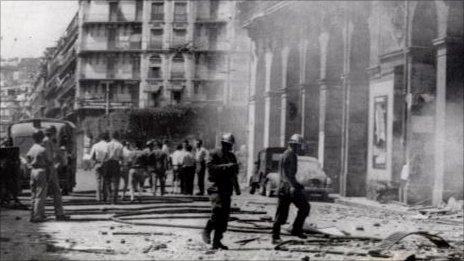

Nine people were injured when riots broke out in the Algerian capital, Algiers, in May

This is on top of a 34% increase in salaries for civil servants given earlier this year.

The new budget law extended a tax waiver on cooking oil and sugar imported from abroad until the end of the year. Previously, the government had introduced several programmes to benefit the youth, including low-interest loans for opening a business and affordable housing.

But in a recent interview, an Algerian official described the government's actions as "a circus", saying it is "doing everything to avoid angering the people".

In early February, the government also lifted a 19-year-old state of emergency law that forbade demonstrations and restricted the formation of political associations.

This month the president is expected to release 4,000 Islamists from prison. Most of them have been held since 1992 when a conflict erupted between Islamists and the military.

President Bouteflika has also launched an ambitious reform agenda that would culminate next year with an amended constitution, new electoral laws and a press code, along with several other key changes aimed at curtailing corruption and easing bureaucratic hurdles.

To ensure the participation of all political forces, Mr Bouteflika nominated his former adviser General Mohammed Touati and Mohammed Ali Boughazi, the former cabinet minister, to organise and lead a national dialogue on reforms.

Both leaders were selected for their connections to the Berber political parties and Islamist leaders, respectively.

Lessons from Libya

In some areas, police have been told to stop collecting taxes from shopkeepers

But concessions, appeasement and reforms are not the only means the government has used to fend off threats of revolutionary change. Propaganda is the other.

In its coverage of Libya, Algeria's official media has highlighted the threats of terrorism, foreign intervention and the overall collapse of the systemic order with images of mass killings and destroyed infrastructure.

But Algeria has not necessarily weathered the storm. The government has had success managing the current crisis but it has to do more.

Further success will depend on the extent to which the president is willing to push for the resolution of what many Algerians consider the core of the country's malaise: Poor living conditions for the vast majority of people and a lack of a transparent and fair political representation.

The current system has long been criticised for lacking popular legitimacy and for being overly controlled by the military. Restricting the role of the military and opening the system could be central to restoring a new and legitimate order.

Making the economic development of the country an urgent priority is also key. If the existing socio-economic problems continue, the population will have no choice but to turn to the inevitable: Revolution.

Only time will tell if the Algerian government has saved Algeria and itself from any radical change.

Hamoud Salhi is professor of political science at California State University (US), and formerly a television and newspaper analyst.

- Published2 June 2011

- Published10 June 2011

- Published9 September 2024