Flying the flag for North Africa's 'Berber spring'

- Published

The Berber flag, seen here in Agadir, symbolises peace and Amazigh unity

While there has been much talk of the Arab spring, ethnic Berbers have played a key role in the changes sweeping through North Africa, which is leading to greater recognition for their culture and language.

In Libya, the group which has been repressed for decades by the Arab majority, has led fierce resistance against Col Muammar Gaddafi's forces in their heartland - the western Nafusa Mountains.

Their flag - bearing the symbol of the Amazigh, as the Berbers call themselves - flew high as territory was captured and or shrouded soldiers as they were buried.

It was also raised aloft in celebration at the annual Amazigh festival in the southern Moroccan town of Agadir as Tamazight was adopted as an official language as part of the country's consitutional changes.

Fathi Khalifa - who serves on the Libyan rebels' governing body, the National Transitional Council (NTC) - says the uprising has given Berbers hope.

"For 40 years, Amazigh Libyans have been oppressed," he says.

"When the era of openness and freedom started, the Libyan people gave some good signals. Today, the situation is very encouraging."

During the rebellion, the NTC has waged a strong media campaign for the support of the Berbers.

Rebel-controlled Libya TV, based in Qatar, broadcasts daily in the Berber language, Tamazight, for two hours, while a newspaper in Tamazight is also published in the Libyan town of Jadu.

An ethnic minority in most North African countries, Berbers see themselves as being oppressed.

Clean break?

But it is in Morocco where the real meaning of the word Amazigh or "freemen" is finding resonance.

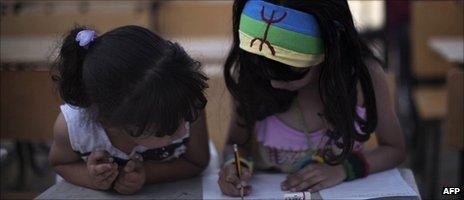

Libyan children have started learning Tamazight at new cultural centres

The North African kingdom recently adopted a new constitution which recognised the Berber tongue, spoken by 60% of the population, as one of its official languages.

According to Abdullah Aourik, founder and publisher of Agadir O'flla, a magazine devoted to promoting the Berber cause, Morocco could well show the way for others to follow and is confident that further change is afoot.

"Our King Mohammed VI is a Berber," he says, explaining that the Moroccan monarch's mother is a Berber. His father claims descent from the Prophet Muhammad, born in what is now Saudi Arabia.

"He is not against us but is helping move our cause forward," Mr Aourik says.

As the Arab conquerors swept across North Africa in the 7th Century they brought with them their language and the new Muslim religion.

Both of these were adopted officially at the expense of the Amazigh language and culture.

But Mr Aourik is confident that greater equality is on its way.

"Fidel Castro's mother was Amazigh, from the Canary Islands, so we are everywhere. They cannot ignore us any longer."

Hope was also in the air at a recent Berber conference in Morocco's port city of Tangier when representatives from five North African countries, as well as the Canary Islands, met to develop a common strategy to achieve greater rights.

Tunisian delegate Khadija Ben Saidane said the demand for the recognition of the Berber language, culture and identity was more likely to succeed in her country since the ousting of long-serving ruler Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali in January.

However, different Berber dialects and social and political aspirations have stymied efforts to achieve a unified series of demands across the region.

Berbers have formed a cultural organisation called Tinas.

"Its name is inspired by the historical name of Tunisia that was faked by the Arabs who tell us that this word comes from the Arab verb meaning 'to be a companion', while tinas means 'key' in the Amazigh language," she says.

In Egypt, around 30,000 Berbers live in the oasis of Siwa near the Libyan border and the Beni Suef regions. They feel an Arab identity has been imposed on them.

According to Egyptian representative Amani al-Weshahy, they want to replace the Arab culture that has dominated since the time of independence leader Gamal Abdel Nasser.

Buses in Agadir, south-west Morocco, now have the city's name in the Arabic, Amazigh and Latin scripts

"We are now asking for the rights of the various cultures to be recognised," she said.

So far none of these Berber activists support making a clean break with their home country.

Algerian Amazigh, mainly from the country's northern Kabylie region, are promoting regional identities which, they feel, will give Algeria stability within a federation.

In the end the meeting in Tangier called for the establishment of a North African union, to embrace all the region's identities, languages, cultures and beliefs.

This would transform the greater Arab Maghreb from an Arab-dominated region into a confederation of states that would take the Berber voice into account.

But without a single unifying dialect and caught between very different situations in each country, their bid for unity and greater rights could easily be once more lost, especially if radical Islamist groups take the place of the deposed despots they helped to oust.

- Published27 July 2011

- Published24 June 2011

- Published11 July 2011