Why protests will not unseat Swaziland's King Mswati

- Published

Mother-of-three Salom Gamedze may be struggling to feed her family and pay school fees for her children's education but she is unlikely to take part in anti-government demonstrations which Swaziland democracy activists have called, starting on 5 September.

Ms Gamedze, 42, lives in a half-brick half-mud hut in the remote Lubombo region of eastern Swaziland. She has no electricity or water and is unemployed.

"I want to get a job so I can send my children to school but there are no jobs for me here and now we cannot even afford to work our land so we are not growing much," she sighed.

"We had dreams for our children, that they would be better than us, become doctors and nurses and make something of their lives, but now that seems like an impossible dream."

Ms Gamedze is like many Swazis: She wants change in a country where two-thirds of the population lives in grinding poverty and a quarter is HIV-positive, but she is unsure about the type of change she wants.

She is unlikely to take part in pro-democracy demonstrations to demand an end to the rule of King Mswati III, who is sub-Saharan Africa's last absolute monarch.

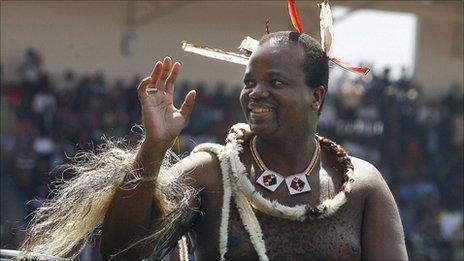

Educated at a British boarding school, he has ruled Swaziland - which has a population of about 1.2m - since 1986.

The king's critics accuse him and his 13 wives of leading a lavish lifestyle, showing little concern for the plight of his subjects - an allegation he denies.

During her interview with the BBC, Ms Gamedze stayed clear of mentioning King Mswati.

'Suicidal to criticise'

For many Swazis he is almost a cult figure. Few of them wanted to talk about him, however discreetly.

One pro-democracy leader said it was "suicidal" to criticise King Mswati, while another pointed out that in Swazi culture he is the final authority so if the opposition went to him to ask for change and he refused, they would have no further avenues to explore.

Salom Gamedze is pessimistic about the future

Despite this fear of challenging the monarch, trade unions and civil society movements have staged several public demonstrations demanding the resignation of Prime Minister Barnabas Sibusiso Dlamini and his cabinet.

The protests follow a worsening economic crisis in Swaziland, forcing the government to ask neighbouring South Africa for a bailout of $355m (£218m) to pay its bills.

But most people - like Ms Gamedze - are reluctant to get involved.

"People do understand that things are not right but they fear a backlash if they speak out. They are worried that if they are seen to be making a stand then they will have to answer to the traditional authority," Sibongile Dlamini, a programmes officer with the Swaziland Council of Churches (SCC), told the BBC.

She said the lack of security of land tenure added to the vulnerability of people, as chiefs - representing the monarchy - controlled land in rural areas.

In one recent case, she said, someone who tried to organise a group discussion about the situation in Swaziland had to pay a fine of two cows.

"This is a person who does not work and has no income so that was a very big fine. What our system has done is suppress people into a state of ignorance and inaction," Ms Dlamini says.

"I think as civil society, we need to go back to the drawing board and work out how to engage people because we need everybody to come together to make the government realise we need change."

State of emergency

Pro-democracy activists argue that King Mswati's "Tinkundla" system of government - which has banned political parties, but allows for a parliament to exist - is a major cause of Swaziland problems.

They say this system has few checks and balances, allowing corruption to flourish.

Former businessman Musa Hlophe, who heads the Swaziland Coalition of Concern Civic Organisations (SCCCO), says the battle to achieve democracy in Swaziland is an uphill one.

Swaziland's 13 queens are accused of profligate spending

"You're talking about 38 years of living under a vicious state of emergency that has produced a generation who know no democracy and who grew up in an environment where people can't talk freely," he says.

Mr Hlophe was among a number of Swazis who lobbied against South Africa giving Swaziland a bailout without strict conditions, arguing the money would just prop up the existing regime.

Although the finer details of the loan agreement are still under discussion, South Africa's government has said the "creation of an open dialogue in Swaziland" was a key condition for the loan.

Mr Hlophe said he hoped that dialogue would take place soon while protests to demand democracy would continue.

From 5 September, the opposition has called a "Global Week of Action on Swaziland", urging people to back their campaign to bring democracy to the monarchy.

Labour protests in April were met by a heavy police reaction leading to teachers being tear-gassed and several foreign journalists arrested.

Last year around 50 people were arrested for taking part in demonstrations and South Africans who showed their solidarity by joining the protest were deported.

Ms Dlamini hopes that despite the political repression, there will be a big turnout at the main protest in Swaziland's capital, Mbabane.

"If it's always the same faces walking through Mbabane the government will continue to say that it's only a minority who are unhappy with the system and nothing will change," she said.

- Published12 July 2011

- Published12 April 2023