Growing protests in Angola alarm long-term leader

- Published

Despite living in a wealthy country, few Angolans have enjoyed the benefits

Political tensions are rising in Angola, where a small but increasingly vocal group of protesters are rattling the cage of the ruling party ahead of elections planned for next year.

Inspired by the downfall of North African regimes, the group of mostly young people, who have no fixed political affiliation, have been staging a series of anti-government street protests which, as in Egypt and Tunisia, have been organised via text messages and social media sites like Facebook and YouTube.

Although only attracting a few hundred people each time at most, such demonstrations are largely unheard of in Angola, where the regime drowns out critical voices through threats and patronage, and trade union action is muted.

The main driver behind the protests is unhappiness that, despite Angola's enormous oil wealth and post-war economic boom, two thirds of people still struggle in grinding poverty, many without running water and electricity.

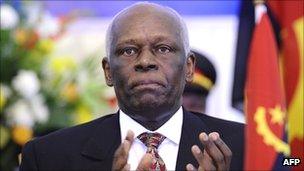

And President Jose Eduardo dos Santos, who last week clocked up 32 years in power, has become a target for this anger amid allegations that he and his family, along with close aides, have been getting rich through corruption and insider deals.

'Nervous' leadership

Following Col Muammar Gaddafi's departure from power in Libya, Mr dos Santos now vies with Equatorial Guinea's Teodoro Obiang for the title of Africa's longest-serving leader, depending on whether you count from when Mr Obiang secured his coup in August 1979 or from when he was officially sworn in as president that October.

The latest protest took place on Sunday, when some 200 youths gathered outside a cemetery in Luanda holding banners calling for the release of fellow protesters imprisoned earlier in the month as well as the end of Mr dos Santos' three-decade rule.

Armed police overpowered the group who were blocked from following the route of their planned march, and after several hours of standoff, the crowd eventually dispersed.

The day before, the ruling Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), which has accused the protesters and opposition parties of threatening national stability, mobilised tens of thousands of its members who marched through different neighbourhoods of Luanda showing their support for the government and Mr dos Santos.

According to state media reports, the chanting marchers carried banners with slogans such as "long live peace and national unity" and "no to disobedience".

MPLA leaders addressed the crowds - who, some claim, had little choice but to attend - accusing the youth and opposition parties of trying to bring confusion to the country and re-start the civil war.

Paula Roque, a senior researcher at the Pretoria-based Institute for Security Studies (ISS), said the scale of the MPLA's counter reaction showed how much the regime was rattled by the protesters.

"I think the MPLA is worried because they know they haven't delivered a peace dividend and that the reality of the country contradicts the external image they like to portray," she said, adding that the high levels of poverty were unacceptable in such a resource-rich country.

Is Jose Eduardo dos Santos facing the beginning of the end of his presidency?

Medil Campos, 25, one of the protest organisers and part of a group called Central Angola, said he was not intimidated by the MPLA or its tactics.

"Everything is manipulated," he told the BBC. "We can see that the government is nervous and they are only doing this because of what we are doing."

Ms Roque said the protests were extremely bold for a country ruled by what she called "sophisticated and discreet intimidation" but she did not believe change would come overnight.

"This is more of a chipping away of the regime," she said. "I do not believe we will have the tornado like we saw in North Africa. Angola is not ready for that. But certainly, there is slowly starting to be a change."

Hotting up

Although there were no arrests this weekend, earlier in the month dozens of people were taken into custody for their involvement in demonstrations and 18 people were jailed, some for three months, for public order offences.

Several journalists were also injured in scuffles between police and protesters, although the youths have blamed secret police infiltrators for instigating the violence in a bid to discredit their movement.

In a move rights groups have condemned as heavy-handed and reactionary, the Provincial Government of Luanda (GPL) has now banned demonstrations in the city centre, a directive which appears to contradict the constitutionally-enshrined right for peaceful assembly.

Despite this and other crackdowns, such as the Ministry of Culture's ban on a new CD by known anti-establishment rapper Brigadeiro 10 Pacotes, Mr Campos said his movement would not give up.

"We are not afraid of this government," he said. "We know what they are capable of, but we will continue with our battle because it is about making Angola better for future generations."

He said they would continue to mobilise supporters through Facebook and other social networks, which he said had been instrumental in providing an alternative platform for sharing information outside of the state-controlled and heavily censored traditional media.

With people now openly challenging the authority of Mr dos Santos for the first time, the question of his succession has sent the country's rumour mill into overdrive.

Earlier in the month a "party source" told a private newspaper that Manuel Vicente, the chairman of the national oil company, Sonangol, would take over the top job.

MPLA spokesman Rui Falcao responded by saying "any scenario is possible", prompting many to read the naming of Mr Vicente, a close friend of Mr dos Santos but not a traditional MPLA member, as a deliberate ploy by the party to test the reaction among rank and file members.

Alex Vines, head of the Africa Programme at London-based think tank Chatham House, said: "President Dos Santos is clearly aware of changes in north Africa and the growing sense in Angola, and especially within the party, that 32 years is a long time."

He believed Mr dos Santos would still likely stand as the top MPLA candidate - the head of state is now chosen from a parliamentary list following changes to the constitution last year.

But he added: The key question is how long will he stand after that - and that is why the politics of succession is hotting up."

Although blighted by civil war for 27 years following its independence from Portugal in 1975, since peace in 2002 Angola's stability has been a magnet for foreign investors, particularly in the oil and construction sectors.

Any upheaval could deter future investment and lead to a slowdown in the country's sustained near-double-digit economic growth.