Will South Africa's 'secrecy bill' become law?

- Published

Lobbying is under way for the bill to be sent back to the lower house for a public interest clause to be inserted

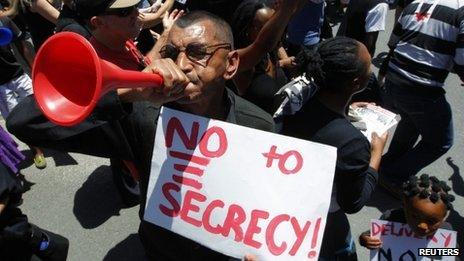

The demonstrations may be much smaller in South Africa, but the fury about a threat to national democracy seems as heated as that of the clamouring crowds in Egypt's Tahrir Square.

The anger follows the passing in Cape Town's parliament of the Protection of State Information Bill, because of its alleged threat to freedom of speech.

Uncharacteristically the parliamentary opposition united in its fight against the legislation proposed by the governing African National Congress, but it was passed by 229 votes to 107, with two abstentions.

In its current version, there are tough sentences of up to 25 years for anyone possessing classified government documents, with no defence of acting in the public interest.

Civil society organisations and all media houses are up in arms demanding that a "public interest" clause be included in what has been dubbed the "secrecy bill". They argue this would allow the media to uncover corruption.

Fortunately for those opposing the bill there is still some respite.

Parliamentary procedure requires the bill to be taken to the upper house of the legislature - the National Council of Provinces, previously known as the Senate.

Lobbying is already under way for it to be sent back to the lower house for the public interest clause to be inserted.

Even if it goes through the upper house, all is not lost.

There is still an opportunity for review as it can be challenged at the Constitutional Court, the highest court in the land - meaning it could be amended before becoming law.

"If passed, this bill will unstitch the fabric of our constitution," the main opposition Democratic Alliance parliamentary leader Lindiwe Mazibuko eloquently put it from the podium in The National Assembly on Tuesday.

Not only the press but ordinary people could suffer under the new law

"It will criminalise the freedoms that so many of our people fought for. What will you, the members on that side of the House, tell your grandchildren one day?" she said.

"I know you will tell them that you fought for freedom. But will you also tell them you helped to destroy it? Because they will pay the price for your actions today.

"Let this weigh heavy on your conscience as you cast your vote. The ANC has abandoned the values of its founders exactly 100 years after it was formed."

'Removing apartheid legislation'

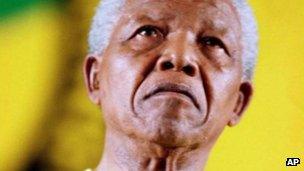

So why does the ANC, the party of Nelson Mandela - the liberator of South Africa from the repressive apartheid laws, want to undo the good work that so many died and were imprisoned for?

One plausible reason is because of an arms deal probe.

President Jacob Zuma recently established a commission of inquiry into the dealings of the controversial multi-billion dollar procurement in 1999 of fighter jets, submarines and other armaments to beef up the country's defences.

One of his former associates, Schabir Shaik, was convicted for corruption in his role in the arms deal.

There is therefore a belief that the contentious bill will assist the state by allowing it to classify some of the information a secret, making it difficult to be disclosed publicly.

"Zuma himself is a securocrat and there's a desire to cover up wrongdoing within government," the chairman of the South African National Editors' Forum, Mondli Makhanya, told the BBC.

He says the ANC "displays the arrogance of power" and that is why the party is proceeding with this bill against all the red light warnings.

MP Luwellyn Landers, the ANC's chief negotiator on the ad-hoc committee that processed the bill, dismissed arguments for the insertion of a public interest clause.

Mr Mandela promised in 1997 that press freedom would never be threatened with the ANC in power

He said the bill contained the same public-interest defence mechanism as the Promotion of Access to Information Act.

The new secrecy law would remove apartheid President P W Botha's 1982 Protection of Information Act from the statute books, Mr Landers said.

Far more than the media and civil society groups, it will be poor and down-trodden people who will suffer most under the proposed law.

They will not be able to hire expensive lawyers should they need to challenge government to know, for example, what had happened to funds earmarked for development of their community.

The ANC's formal alliance with the South African Communist Party and the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu) is also divided on the issue - and could stop the bill being signed into law.

Cosatu is against the bill in its current form as is Nobel Peace laureate Archbishop Desmond Tutu - the moral compass of the nation.

The Nelson Mandela Foundation has also expressed its concerns about the bill.

Nelson Mandela once said that press freedom would never suffer in South Africa "as long as the ANC is the majority party".

Let us hope this bill will not prove him wrong.

- Published22 November 2011

- Published5 October 2011