Angola: Ten years of peace but at what price?

- Published

Most Angolans are yet to feel the benefits of the country's oil wealth

There may be much that is shiny and new in Angola, but 10 years after the end of the war many ghosts remain, as Louise Redvers reports for BBC Focus on Africa magazine.

It is a milestone that at one time few would have thought possible. On 4 April, Angola marks a decade since the end of the 27-year civil war which devastated the country, claiming countless lives and displacing millions.

The conflict involved three different liberation movements and saw intervention from the former Soviet Union, Cuba, the United States and apartheid South Africa.

How times have changed. Today Angola can now boast of a booming economy - forecast to grow 12% this year - and a growing regional and international diplomatic profile.

Angola's physical transformation since the end of the war has also been immense.

Oil revenues and associated Chinese loans have bankrolled an ambitious national reconstruction programme of roads, airports, bridges, hospitals and schools.

In the sprawling cities, where the war-weary sought refuge during the height of the conflict, urban slums are being given a facelift.

And once productive agricultural fields are now being cleared of landmines ready for replanting; industries like cotton and coffee are being revived and old copper, iron and gold mines are being re-opened for prospection.

Meanwhile, foreign investors are flocking to Angola hoping to share in the boom times and Luanda's tiny Fourth of February airport is overwhelmed by new flights coming from across Africa as well as Europe, Asia and the Middle East.

African success story?

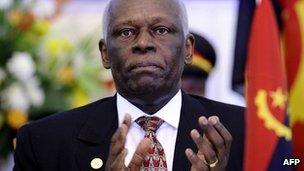

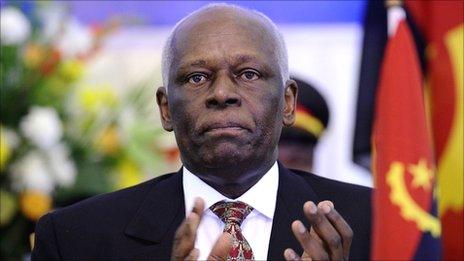

The president of nearly 33 years, Jose Eduardo dos Santos, and his MPLA party remain the dominant power in the country, having claimed a military victory over rivals Unita following the death of rebel leader Jonas Savimbi in February 2002.

Senior members of the MPLA - which won an 82% majority in the 2008 legislative election, the second in Angola's history - have a tight grip over all aspects of the country's economy and both state and private media are heavily biased in the government's favour.

On paper, and in the view of the ruling party, Angola is an African success story - an example of how a war-torn nation can rebuild itself in peace.

In fact Mr Dos Santos sees himself as a regional elder and this year holds the presidency of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the Community of Portuguese Language Countries.

Angola is now even helping to rescue its former colonial power, Portugal, which has been hit hard by the Eurozone crisis and is selling off state and private assets to raise cash. But scratch below the surface and the picture is less pretty.

Despite the country's rapid economic growth - rated as faster than China's during the past decade - it is estimated that up to half the country still live on less than $2 (£1.25) a day.

There may be vast new housing estates with neat gardens and swimming pools springing up around the country, but for the majority of Angolans, home is a shared bed in an unpaved, overcrowded slum with limited access to running water, sanitation or electricity.

Unemployment remains stubbornly high and despite huge investments, the roll-out of mass education is yet to yield tangible benefits. Health services also remain severely limited. This is due to a lack of skilled professionals as well as pervasive corruption.

'Superficial society'

Rates of child mortality have decreased significantly since the end of the war, but one in five youngsters still die before their fifth birthday and the country remains near the bottom of the United Nations Human Development Index, ranked 148 out of 187 countries.

The family of President Jose Eduardo Dos Santos controls a large chunk of Angola's economy

"In 10 years of peace the government has not delivered a true peace dividend to the Angolan people," says Paula Roque, a political analyst and Angolan expert at Oxford University.

"It makes no sense that Angola should continue with the level of poverty we are seeing when there is so much money coming from oil."

But for Ms Roque the issue goes deeper than poverty alleviation. She questions just how peaceful and reconciled Angola really is when the ruling party has, since the end of the war, silenced all narratives except its own and imposed on the population what she calls a "superficial society".

It is true that Angola's school-taught official history belongs to the MPLA, as do the nation's symbols like its flag and national anthem.

This is a point Unita, now a parliamentary opposition party, tried to contest during the drafting of the country's new constitution in 2010.

Perhaps emblematic of this is the continuing fight carried out by Mr Savimbi's supporters to return his remains to his home town for an official burial.

All the while the government is pouring millions of dollars into a mausoleum and a museum for the country's first President Agostinho Neto who died in 1979 and is hailed as a national hero.

Justin Pearce, from the London School of Oriental and African Studies, shares the view that while Angola looks "remarkably peaceful" it has in fact undergone no formal or deliberate reconciliation process.

"The general message from the government is that now the war is over, everything else will look after itself," he explains, adding that the deep complexity of past allegiances have also made people reluctant to confront their past for fear of creating trouble for themselves or their families.

Signs of discontent

Mr Pearce highlights that during the war members of the same family may have been actively involved in Unita and in the MPLA, and a person may even have been involved in both parties at different times of his or her life.

"The soldiers who fought in the war had mostly been conscripted and had no choice in the matter and at a civilian level - if you were captured, or if a different army took control of the place where you were working, then your own survival depended on professing loyalty to and working for that side," he says.

There were rare anti-government protests last year

Mr Pearce, who has interviewed former soldiers in central Angola, points out that integration and reconciliation appears to be very much on the MPLA's terms.

Ms Roque adds: "There has been no conciliated narrative about the war or Angola's past. It is still struggling to define who it is and there's very serious discontent at many levels."

This discontent showed its face last year when a group of young Angolans staged rare protests against the government and called for the resignation of the president, who vies with Teodoro Obiang Nguema of Equatorial Guinea for the unenviable title of Africa's longest-serving leader.

Although small in size and quickly put down by Angola's notoriously tough police force, the demonstrations revealed a free-thinking new generation which is not afraid of the MPLA or scarred by war experiences.

The party reacted by accusing those involved of trying to destroy the peace process and promote "national insurrection".

State media was filled with religious leaders calling for peace to be restored and political figures condemning what they said were "acts of criminal insubordination" that threatened the country's stability.

Ms Roque suggests that the MPLA has actually taken "ownership" of the country's relative peace as a commodity, and is fiercely protective of it.

There is growing consensus, however, that it is the ruling party itself which is increasingly unstable, unsure of how to deal with this new wave of criticism which challenges its hegemony and threatens its access to state resources.

Angola is scheduled to go to the polls later this year. There is little doubt the MPLA will win.

This is as much down to the weakness of the opposition as to the ruling party's likely manipulation of the voting process. But it is what follows next that is critical.

"There are cracks appearing in the MPLA's system of governance and I truly believe that change is coming to Angola," says Ms Roque.

"There are many ghosts and all are the ingredients for a palace coup. We have to hope the change will come through dialogue and not violence."

- Published26 September 2011

- Published21 February 2023

- Published1 September 2011