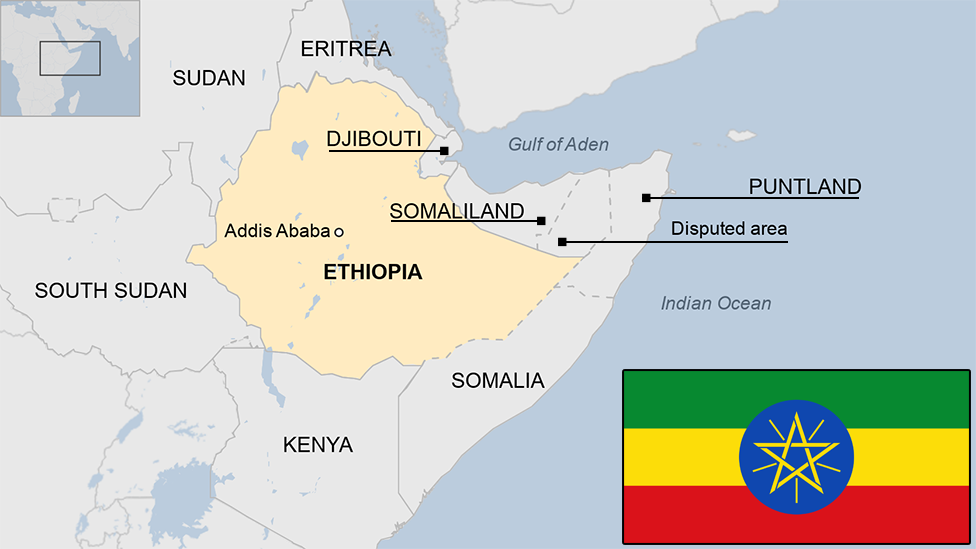

Obituary: Ethiopia's Meles Zenawi

- Published

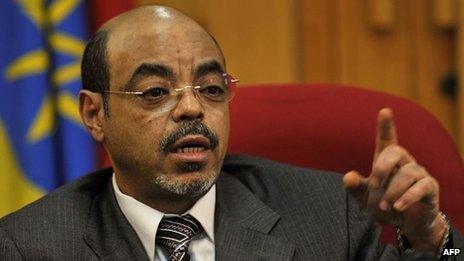

Meles Zenawi is seen here in 2012

Meles Zenawi, who died in hospital at the age of 57, was the cleverest politician to emerge from the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF), one of the armed movements which spear-headed the struggle against Ethiopia's military regime in the 1970s and 1980s.

Born into a middle-class family in Adawa, Tigray, in Ethiopia's northern highlands, he dropped out of university to join the insurrection.

After the military council (Derg) led by Mengistu Haile Mariam was finally overthrown in 1991, Mr Meles first became president in a transitional government and then, in 1995, prime minister. He went on to dominate Ethiopian public life until his death.

There were some challenges to his leadership, notably after the secession of Ethiopia's most northerly region, Eritrea, when he was blamed for letting it go too easily, and after the subsequent border war.

Ethiopia won that war at a huge cost but the prime minister outmanoeuvred or sidelined his critics within the party, and emerged more powerful than before.

Austere

Mr Meles was marked forever by his years in a guerrilla movement, when sloppiness or lack of discipline could lead to the death of comrades and the failure of a mission.

He himself was austere and hardworking, kept a very tight grip on even minor details of government and dealt ruthlessly with any signs of dissent within the leadership.

He married another TPLF veteran, Azeb Mesfin, a businesswoman and member of parliament.

The couple had three children and lived, by all accounts modestly, in a small house inside the old imperial compound in the centre of the capital, Addis Ababa.

He was known to enjoy playing tennis but did not take holidays and almost never smiled.

His widow Azeb Mesfin is also a former guerrilla

The one time when he was seen relaxed and smiling - at the country's millennium celebrations - wearing Ethiopia's comfortable traditional dress and dancing with his wife, everyone talked about it for days.

Under his leadership, a closed and secretive country gradually opened to the outside world.

Despite his own Marxist roots, he welcomed outside investment. Big foreign companies are coming in - especially in the agricultural sector - and skyscrapers are rising above the capital.

But some things have not changed.

State- or party-owned companies dominate the economy while land is still owned "by the people", making it impossible for farmers to buy or sell their farms.

And Ethiopia is still a tightly controlled society, retaining the old system of Kebeles - local committees which oversee almost every aspect of daily life.

For a time Mr Meles was an international favourite, the preferred face of a "New Africa", praised for his emphasis on grassroots rural development and his government's relative lack of corruption.

He was also formidably intelligent, an extremely articulate speaker and a welcome ally in the US war on terrorism.

Ethiopia has fought a long rebellion in its own Somali-speaking region and the rebellion's backers within Somalia itself. He was able to link this to America's preoccupation with what it saw as an Islamist threat in the Horn of Africa, and forge a military and political alliance with the United States.

However, Mr Meles's reputation as the face of the African renaissance flagged as repression inside Ethiopia increased.

Huge shock

A brutal crackdown followed a surprisingly good opposition showing in the 2005 elections.

More recently, new anti-terrorism legislation was used against journalists, bloggers and other critics of the government.

And attempts to extend government control over what was being said in mosques brought Muslim protesters out on to the streets.

Meles Zenawi led Ethiopia for more than 20 years

Meles Zenawi's personal dominance has also raised questions over the succession.

He led Ethiopia for more than 20 years and, although still only in his fifties, had said before he became ill that he would stand down from the premiership at the next election.

There is a deputy prime minister, Hailemariam Desalegn, who is also foreign minister, but what one commentator described as Mr Hailemariam's "less-than-driven persona" may make him a better deputy than a leader.

And the issue is complicated by the fact that although Ethiopia is ruled by a coalition of regional parties, the party from Tigray, the TPLF, has continued to hold most of the real power, in both the army and the government.

Mr Hailemariam is from the south, from one of the regions with the least political clout.

This may be a good background for a deputy, but it could make it difficult for him to hold on to his position in the face of challenges both from Tigrayans who do not want to give up their supremacy, and politicians from other powerful regions who have felt themselves excluded for too long.

- Published21 August 2012

- Published2 January 2024