Profile: Chad's Hissene Habre

- Published

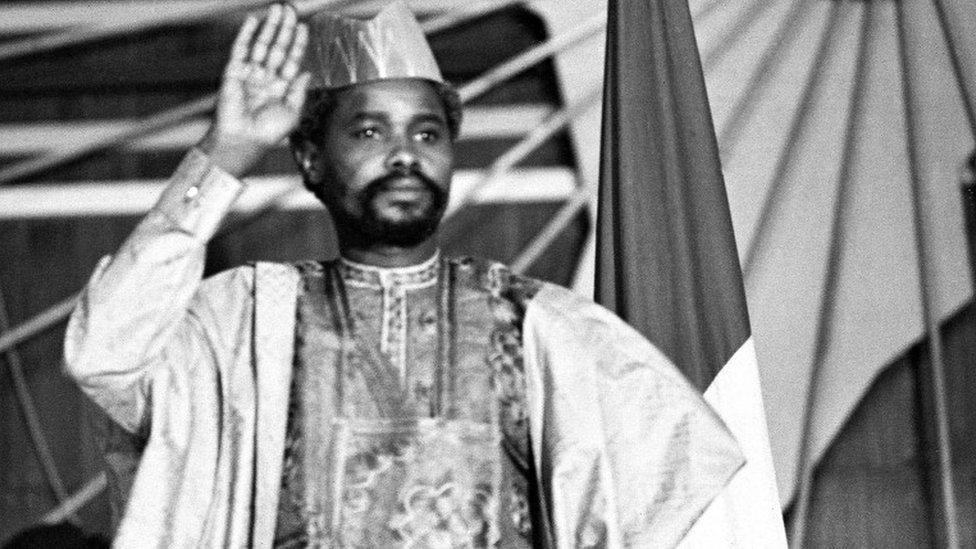

Hissene Habre refused to recognise the legitimacy of the court which tried him

Chad's former leader Hissene Habre has been dubbed "Africa's Pinochet" because of the atrocities committed during his eight-year rule.

He was sentenced to life in prison for crimes against humanity, in the first African Union-backed trial of a former ruler.

It was the culmination of a 17-year battle by victims of his rule to bring him to justice.

A Commission of Inquiry formed in Chad after he was deposed in 1990 said his government carried out some 40,000 politically motivated murders and 200,000 cases of torture in the eight years he was in power.

His dreaded political police force, the Documentation and Security Directorate (DDS), committed some of the worst abuses.

Habre, 73 denied any knowledge of the murders, torture, and rape that he was convicted of.

He seized power in 1982 from Goukouni Oueddei, a former rebel comrade who had won elections.

It was widely believed that he was backed by the CIA, as a bulwark against Libya's Colonel Muammar Gaddafi.

His coup came in the middle of a war with Libya over the disputed Aozou strip.

Habre ruled Chad from 1982 to 1990

Backed by the United States and France, Habre's forces drove out the Libyans in 1983.

He first came to the world's attention in 1974 when a group of his rebels captured three European hostages and demanded a ransom of 10 million francs.

One of the hostages, French ethnologist Francoise Claustre, was held for 33 months in the caves of the Tibesti volcanic complex of northern Chad.

However, this episode did not prevent the French from later backing Mr Habre.

'Swimming pool torture'

He was born to ethnic Toubou herders in northern Chad but excelled at school and was eventually spotted by a French military commander, who organised a grant for him to study in France.

As a senior local official, he was sent to persuade two rebel chiefs, including Mr Oueddei, to lay down their arms; instead he joined their struggle.

During Habre's time in power, he faced a succession of rebellions but lobby group Amnesty International has said this does not excuse his government's human rights abuses.

"The Chadian government applied a deliberate policy of terror in order to discourage opposition of any kind," Amnesty says.

Human rights groups say the DDS was under the tight personal control of Habre.

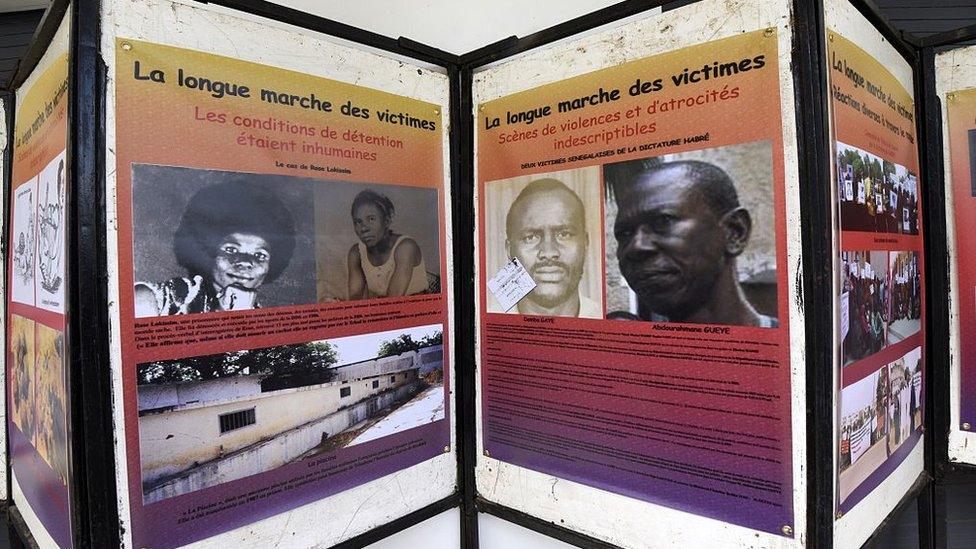

An underground prison, known as the "Piscine" because it was a converted swimming pool was one of the DDS's most notorious detention centres in the capital, N'Djamena, while Amnesty reports that some political prisoners were held at the presidential palace.

Survivors said the most common forms of torture were electric shocks, near-asphyxia, cigarette burns and having gas squirted into their eyes.

Relatives of victims have finally got justice

Sometimes, the torturers would place the exhaust pipe of a vehicle in their victim's mouth, then start the engine, Amnesty says.

Some detainees were placed in a room with decomposing bodies, other suspended by their hands or feet, others bound hand and foot.

One man said he thought his brain was going to explode when he was subjected to "supplice des baguettes" (torture by sticks), when the victim's head is put between sticks joined by rope which are then twisted.

Others were left to die from hunger from the "diete noire" (starvation diet).

US-based rights group Human Rights Watch says that members of any ethnic group seen as being opposed to Habre were targeted: The Sara in 1984, the Hadjerai in 1987 and Chadian Arabs and the Zaghawa in 1989-90.

Habre was eventually deposed by current President Idriss Deby, an ethnic Zaghawa, who has been accused of favouring members of his own community.

After being ousted, he fled to exile in Senegal, where he has kept a low profile.

However, he became involved with the local Tijaniyya Islamic sect, married and four of his children were born there.

"I can say that my children don't know Chad. Their country is Senegal," Habre's wife, Fatime Raymonde, once told a local newspaper.

Legal wrangles

His victims, backed by Human Rights Watch, have been trying to bring him to justice ever since.

First, a Senegalese court refused to put him on trial, saying it did not have jurisdiction over alleged crimes committed in Chad.

His victims then turned to Belgium and, after a four-year investigation, a judge issued a warrant for his arrest in 2005 as the country's universal law allows its courts to prosecute human rights offences committed anywhere in the world.

The Senegalese authorities responded by putting Habre under house arrest, but there have since been years of wrangling about what do with him.

The government of former Senegalese President Abdoulaye Wade changed its position on whether to try him several times, its key concern being about the funding of such a trial.

Four extradition requests from Belgium were denied and the African Union (AU) urged Senegal to prosecute Habre "on behalf of Africa".

Mr Wade agreed to do so and by 2008 the country's constitution was amended to allow the prosecution of war crimes and crimes against humanity in Senegal even if they were committed outside the country.

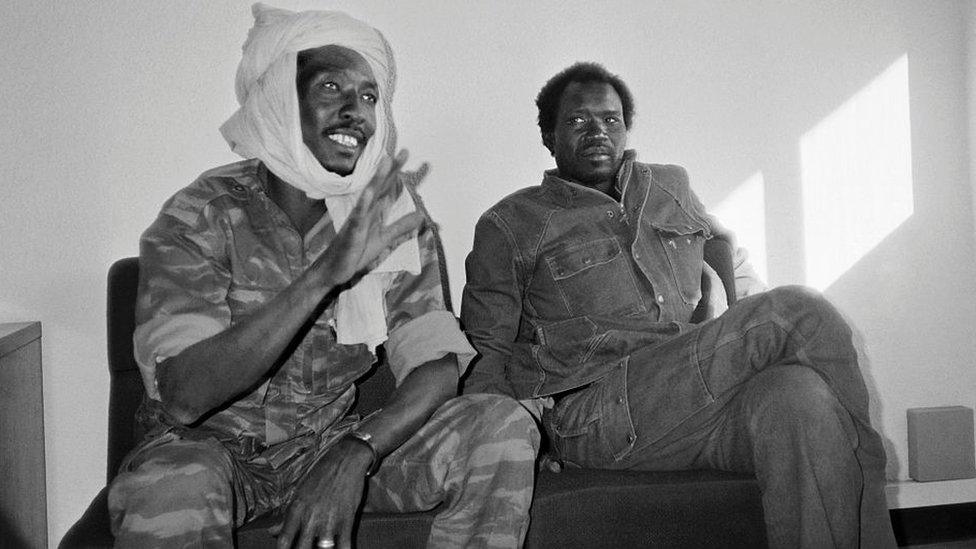

Idriss Deby (L) overthrew Habre in 1990

But in 2011, Senegal unexpectedly announced that it would repatriate Habre to Chad, where he had been sentenced to death in absentia for planning to overthrow the government.

The plan was stopped following a plea from the UN, which feared he could be tortured on his return.

In July 2012, the International Court of Justice at The Hague ordered Senegal to either put him on trial "without delay" or extradite him to Belgium.

A month later, Senegal and the AU signed a deal to set up a special tribunal to try the former leader.

Until his arrest, Habre lived in the quiet Ouakam neighbourhood of the Senegalese capital, Dakar - guarded by two security agents - and was seen occasionally at the local mosque for Friday prayers.

Now, he will spend the rest of his life in prison, unless he wins an appeal against his conviction and sentence.

- Published27 March 2012