Thuli Madonsela: South Africa's corruption crusader

- Published

Karen Allen has been speaking to the feisty investigator who has been dubbed one of the most influential women the world

When Thuli Madonsela's daughter asked her over breakfast how it felt to be "South Africa's biggest tell-tale", the public protector just smiled.

It was an understated reaction from the woman likely to go down in history as the person who rattled President Jacob Zuma more than any other figure in contemporary South Africa, exposed the growing fissures in the ruling African National Congress (ANC) and went from being a shy trade unionist to an internationally feted global leader.

Ms Madonsela's inquiries over her years in office as public protector have led to the sacking of some of the most senior figures in the country.

She has investigated police chiefs, opposition politicians - and even the president himself over multi-million dollar security upgrades to his private Nkandla home.

It was probably not a surprise that on Friday, the woman many just call Thuli spent her final hours in office in court, seeking to defend her country's hard won democratic ideals and the release of her interim report on corruption and cronyism - what's rather clumsily called "state capture" here.

'Extraordinary'

In short, it expected to describe how unelected businessmen - who allegedly wield huge influence over President Zuma - were able to call the shots on who should and should not get a ministerial job.

Much of her interim report is believed to focus on a family known as the Guptas, but the practice of patronage politics and opaque practices over the awarding of government contracts and jobs goes much deeper than just one family.

For some, it is perhaps surprising that the softly spoken mother of two has survived seven years in her role. But it is a credit to South Africa's robust constitution that the public protector has withstood attempts to remove her, harm her physically with death threats and smear her name.

If anything, her popularity has grown, with a prominent international think-tank recently voting her among the world's top five most "extraordinary women".

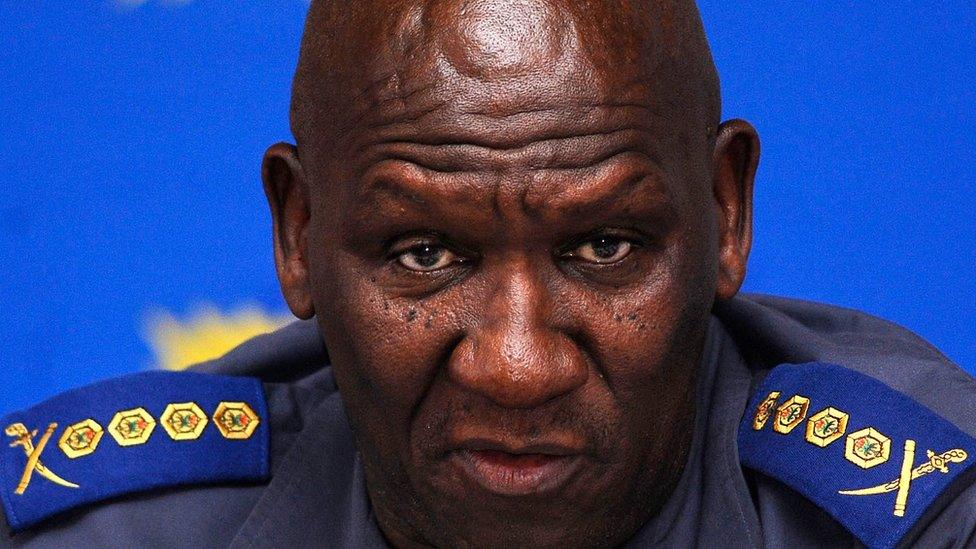

Thuli Madonsela's work led to the suspension of national police chief Bheki Cele in 2011

In her most recent investigation, she has been accused by the Guptas' lawyers of abusing her position and overshadowing the legal process.

Others say she has overstepped the mark, with the ANC Youth League dismissing her as "insecure" - a woman willing to besmirch the name of South Africa to the world.

Yet David Lewis, chief executive of the campaign Corruption Watch, has described her as "South Africa's most important bulwark against corruption" who has inspired hope among millions of citizens looking for better service delivery.

And the very man she investigated back in the day - Julius Malema, the leader of the Economic Freedom Fighters - is now among her most vocal defenders as he calls for President Zuma to resign.

Although her title of public protector may sound mundane, Ms Madonsela has captured the imagination of South Africans and the media for her no-nonsense style and her ability to deliver.

She's presided over tens of thousands of investigations and once exposed the president as having run roughshod over the country's prized constitution.

Add to that her credentials as a former lawyer in the trade union movement during the fight against white minority rule and her involvement in the drafting of South Africa's post-apartheid constitution, and she's earned the respect of the ruling ANC and opposition alike.

On a trip through the townships of Soweto with Ms Madonsela four years ago, I got a sense of a women who displays a deep sense of compassion and humility.

Sewage ran through the streets after what neighbours claimed was a dodgy tender that led to the water pipes bursting.

As she picked her way through in a pair of smart high heels, Ms Madonsela reflected on the state of her beloved country: "I don't remember it being this bad."

Frustration with the state of public services have led to protests

She described how she grew up in Soweto, the proud heart of the liberation struggle rule. And yet, "things were different then".

She accepts the arguments of her critics that 300 years of colonial rule and 40 years of apartheid cannot be corrected overnight and that the seeds of corruption were sown long before the first post-apartheid elections in 1994.

But, she says, if "visible action is taken" against corrupt officials now, then it sends the message to people that "if you are thinking about it - then don't".

Wounding enemies

The public protector has risen out of the bureaucratic morass to become a breath of fresh air for a South African public clamouring for more accountability from their public servants and leaders.

She has called for constructive dialogue rather than rioting when service delivery fails, and has always been publicly promised by ministers that despite past attempts to muddy her name, they'll allow her to do her job, whatever her investigations unearth.

With the battle to find a new leader of the ANC at the end of next year, the stakes are higher than ever.

Ms Madonsela knows that corruption allegations can be used to wound political enemies and her successor will be under pressure to follow her tough no-nonsense style.

Some fear Busisiwe Mkhwebane, a former diplomat (and some claim a spy), may not have the stomach for this

But it is perhaps unfair, some say, to pre-judge.

After all, Ms Madonsela "is not a superwoman, she's just an ordinary person doing her job" is one anti-corruption campaigner's blunt assessment of Ms Madonsela.

With a number of biographies expected to be published soon, South Africa's one woman corruption crusader may still go on to disprove that.

- Published14 October 2016

- Published13 October 2016

- Published14 December 2015

- Published17 October 2011

- Published9 July 2024