Viewpoint: Ethiopian PM Meles Zenawi's death could create regional turmoil

- Published

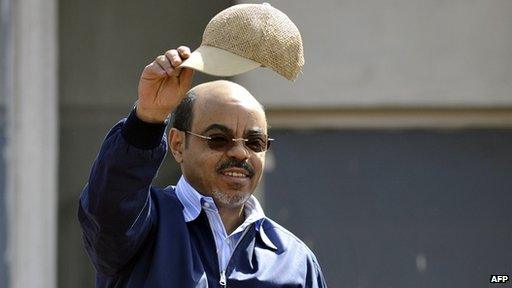

Meles Zenawi ruled for more than two decades after helping oust the former government

The death of Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi has thrown the populous Horn of Africa giant into a period of deep uncertainty and created a serious leadership vacuum in the region with profound geopolitical implications.

Concern is mounting about the potential of a vicious power struggle in Addis Ababa, triggering a negative chain reaction across the region.

For many of Ethiopia's Horn allies, the death has come at an awkward moment, not least because a delicate political transition in Somalia is incomplete and under serious strain, and a stand-off between South Sudan and Sudan risks dragging the region into a new armed conflagration.

Mr Meles was a complex figure, hard to pigeon-hole, much less force into a one-dimensional portrait frame.

A mystique has over the years grown around his personality and politics, making the task to objectively assess his legacy difficult and highly fraught.

To use a Churchillian phrase, the man was a riddle and a mystery inside an enigma, and by extension so too the secretive state he presided over.

But he was the one African leader who was impossible to ignore.

'Increasingly intolerant'

The diminutive ex-guerilla leader was a towering figure whose austere, unsmiling and understated public persona often belied his great influence and charisma.

Since 1991 he has been the undisputed and pre-eminent key player in the Horn - a formidable strategist whose role remained indispensable in the regional efforts to resolve deadly conflicts and contain militant Islamism.

A period of national mourning was announced on Tuesday

Domestically, his legacy is contested. To his ardent fans, he was a true revolutionary impelled by a great sense of mission to overturn the residual feudal and Stalinist structures of the ancient regime.

He was the outsider whose genius led to the overthrow of an entrenched and deeply loathed dictatorship.

His message of social justice and modernisation resonated with many in the homeland, especially the marginalised "lowlanders" in Oromia and Ogadenia.

His concept of revolutionary democracy and ethnic federalism promised to create a fairer and inclusive order.

Measured against these lofty and progressive ideals, his record has, at best, been patchy and rather uninspiring.

The much-vaunted ambitious economic modernisation and liberalisation programme has created a new middle class, attracted huge foreign investment, spawned massive infrastructure projects, spurred economic growth and generally transformed the skylines of the major cities such as Addis Ababa and Mekele.

But it has not tackled the deep structural and systemic problems and inefficiencies that have hampered real growth. The Stalinist land tenure system and the complex bureaucratic system are still intact, and the vast majority remain trapped in poverty.

The democratisation and political reform process, which Mr Meles himself termed "work in progress", has long stalled.

Since the disputed May 2005 polls, the regime has increasingly become intolerant and autocratic, using a raft of new legislation to stifle and criminalise dissent and lock up opponents.

'Discreet purge'

A plethora of old and new armed ethnic factions continue to wage low-level insurgencies in the periphery. The new policy of engagement and piecemeal peace pacts with a select few has so far only succeeded in managing the problem and buying the regime more time.

Feeling vulnerable and insecure, Mr Meles has in the last few years become a leader whose overriding domestic political manoeuvres and calculations are driven by one instinct: regime survival.

He orchestrated a discreet purge of the ruling Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) and the administration, demoting, sidelining or reassigning key potential rivals and opponents.

His death has certainly created a leadership vacuum at the top and with no clear figure groomed to succeed him, the battle for succession could prove destabilising.

That said, the prospect of a large-scale upheaval, as some fear, is highly unlikely, partly because the country has a powerful, highly disciplined and cohesive army and security apparatus.

The opposition can, in theory, capitalise on the disarray within the ruling party to advance its goals and press for an early poll, but that looks difficult given the narrow factionalism and disorganisation within its ranks, not to mention the fact most of the influential opposition figures are either in exile or locked up.

Mr Meles has continued to enjoy good press in the region and across much of Africa, even as his stature diminished domestically.

He is hugely admired and many seem prepared to overlook his personal frailties and forgive his leadership shortcomings for one simple reason: no other African leader has in recent times deployed such great intellectual energy and firepower and used his diplomatic talent and influence to articulate the continent's key priorities and demands at global forums.

He did put Africa on the map, and as a skilled and effective negotiator and spokesman he certainly forced leaders in the developed world to listen. But whether this feat alone qualifies him to join the pantheon of the continent's great visionaries, like Kwame Nkrumah and Nelson Mandela, remains debatable.

Not in contention though is the fact that the late prime minister - almost single-handedly - transformed Ethiopia from a deeply conflicted and war-wracked peripheral Horn of Africa state into a supremely self-assured African diplomatic and military powerhouse.

From the mid-1990s and up until 2005, Ethiopia was a key stop for high-level Western dignitaries visiting the continent, and Mr Meles the must-see African leader whose advice and counsel was sought.

Many embraced him as a reformer and an elite member of the so-called "new breed" of African leaders.

The Ethiopian leader cultivated the new friendship and used it to forge strategic partnerships to raise his country's profile and advance its geopolitical and strategic national interests.

He swiftly rebuilt and modernised the army, initially in a bid to achieve parity with Sudan and negotiate a detente from a position of strength, but subsequently to "tame" a belligerent Eritrea, with whom relations had began to dramatically deteriorate a few years after its independence in 1991.

The two countries have since fought two bloody and costly border wars beginning from 1998. A peace pact and a border arbitration treaty brokered by international mediators failed to end to conflict permanently, partly because Addis Ababa refused to fully abide by the terms of the accords and to return the tiny barren piece of land awarded to Eritrea.

Somali anxieties

Ethiopian troops have helped Somalia fight militant group al-Shabab (pictured)

Hostilities have continued to simmer ever since, and periodic flare-ups are common along the volatile border.

It is plausible the death of Mr Meles may - far from creating opportunities for dialogue - spur Eritrea into escalating the tension.

That would be a disastrous and risky gamble which Eritrea must be dissuaded from taking. It is unlikely this is a course of action that would help it secure its perceived legitimate rights, much less win it friends in the region and beyond.

In Somalia, Ethiopia's military presence in the past year has been instrumental in putting the pressure on the militant group al-Shabab. Thousands of Ethiopian troops now control a number of key strategic areas in south-central Somalia.

The death of Mr Meles has raised new anxieties among the regional allies with troops in Somalia.

There are growing fears a destabilising succession battle and power struggle in Addis could potentially complicate matters and jeopardise the whole mission. Kenyan Prime Minister Raila Odinga said as much in a recent radio interview.

Such fears are understandable, considering Ethiopia's history and political fragility.

However, there is hope too the country has achieved a level of maturity and that it has the institutional mechanisms and the structural resilience to weather the current storm and ensure a smooth transition that allows for policy continuity in Somalia.

- Published21 August 2012

- Published21 August 2012

- Published21 August 2012