Viewpoint: Will South Africans' anger boil over?

- Published

South Africa has replaced Brazil as the most unequal society

The massacre last week at the Lonmin-owned platinum mine in South Africa's North West province, which left 34 miners dead and 75 injured when police opened fire on striking workers, shows a colossal lack of leadership at almost all levels - the government, trade unions, business and the police.

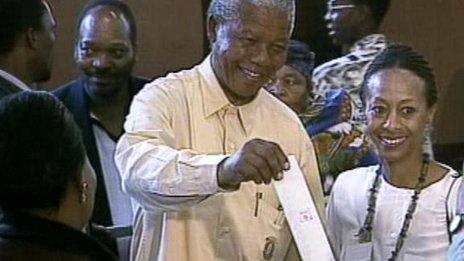

The killings, reminiscent of the brutal days of apartheid, have left many South Africans anxious about the direction of the country, 18 years after it became democratic under the now-retired Nelson Mandela's leadership.

The fact that no-one in responsibility has yet resigned - the government minister in charge of the mining industry, the police chief, the CEO of Lonmin, which is listed on the Johannesburg and London stock exchanges, and trade union leaders - shows the lack of accountability in South African society.

The strike and subsequent violence at the mine shows that the expectation of many black people that their lives will improve in democratic South Africa has largely been dashed.

It is true that the African National Congress (ANC) - the liberation movement now in government - has provided low-cost housing, education, health care and other services to the poor, but it has not done enough of this.

In many parts of South Africa, basis services are either non-existent or of a low standard.

People who can afford it rely on the private sector for education, health and security by employing armed guards to protect their homes and businesses.

'Despair and frustration'

Last year, South Africa replaced Brazil as the most unequal society, with the gap between the poorest and richest individuals the highest in the world.

There are fears the anger at the Lonmin mine will spread

Since apartheid ended, the overall wealth distribution has not changed much. The majority of black South Africans are still impoverished while white citizens are generally better off.

South Africa does not have a system based on meritocracy, which rewards hard work and excellence.

As a result, a small black elite, from the ranks of the ANC and its trade union ally, the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu), has become fabulously rich through shares in long-established white companies, winning government contracts and holding top posts in the public sector - all under the guise of black economic empowerment.

There has been no genuine effort to lift black South Africans out of poverty by giving them quality state education and technical skills, or to help small businesses grow.

Neither has economic growth been accompanied by serious moves to diversify the economy - from exporting raw materials to developing industries that would boost employment.

The impact of the global economic crisis has made things worse. Economists estimate that between 2007 and 2009 nearly one million jobs were lost, while the chief executives of top companies continued to get huge bonuses.

Poor South Africans are caught up in a sense of despair and frustration, which explains the frequent protests over a lack of services in residential areas and now the violence at the Lonmin-owned mine.

But South Africa's leaders seem to believe that the country's mineral wealth - gold, platinum and diamonds, among others - will see it through its economic problems.

They are being complacent - and risk social upheaval on a scale they will not be able to manage.

William Gumede is Honorary Associate Professor, Public and Development Management at the University of the Witwatersrand and author of Restless Nation: Making Sense of Troubled Times

- Published19 August 2012

- Published20 August 2012

.jpg)

- Published23 August 2012

- Published9 July 2024