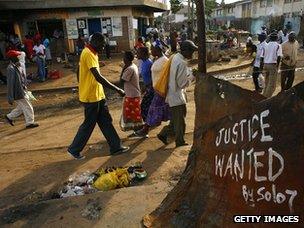

Viewpoint: Can Kenya avoid election bloodshed?

- Published

More than 1,000 people died in violence around the 2007 election - and there are fears of more deadly disturbances as Kenya heads to the polls again

Four years after the worst political crisis since it gained independence in 1963, pre-election tensions are mounting in Kenya. Writer Gray Phombeah believes the country is set for more bloody clashes amid the polling.

In what some see as a flashback to the horrors of Kenya's post-election violence of 2007 and 2008, episodes of inter-ethnic violence, killings and the use of hate speech have increased.

These disturbances are a warning the country could descend into violence worse than the crisis around the disputed general elections in December 2007.

The clashes began in the Tana Delta region, where more than 100 people were killed in August in fighting between the Pokomo people - mostly farmers growing cash crops by the Tana River - and the Orma, semi-nomadic cattle herders, in what appeared to be a dispute over land and water.

In September, the killing of a Muslim cleric was followed by days of deadly riots in the port city of Mombasa.

Since then, junior minister Ferdinand Waititu has appeared in court charged with hate speech and inciting violence in the capital city Nairobi.

More violence has also been reported on the coast of Kenya and in the north-eastern part of the country. The outbreaks have sparked fears that, as the scramble for votes intensifies ahead of the March 2013 poll, the killings could herald another bloody election season.

Political interference

Following the 2007 election and its violent aftermath, a power-sharing government was eventually formed in February 2008 - but by then at least 1,000 people had been killed and tens of thousands displaced.

The violence was so serious that former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan flew into Nairobi, external to steer meetings between the two main political parties' leaders, the Orange Democratic Movement's Raila Odinga and the encumbent, Mwai Kibaki of the Party of National Unity.

A referendum on a new constitution in August 2010 produced a resounding "yes" vote, devolving power and establishing a bill of rights.

But efforts to set up a local tribunal to prosecute suspects of the election killings were blocked by the politicians who were implicated, external.

With official reports still to be published, many Kenyans are still unable to put the violence behind them

So were attempts to undertake land reform, police reform and enact the Integrity and Leadership Bill. Other ambitious reforms whose need had been exposed by the election were not pushed through.

The big debate now is about the two politicians who are due to appear before the International Criminal Court at The Hague just weeks after the 2013 election, charged with displacing, torturing, persecuting and killing civilians during Kenya's election crisis.

Former finance minister Uhuru Kenyatta, and William Ruto, arguably Kenya's most divisive political figure, both deny the charges and are still running for president.

Mr Ruto is widely accused of instigating violence but revered as a hero within his ethnic community, the Kalenjin.

Mr Kenyatta is the son of Kenya's former leader Jomo Kenyatta.

Their presence in the electoral contest has raised fears of fresh violence. And Mr Annan - on hand to mediate after the previous election - last week warned, external the country was in danger of spiralling into serious violence once more.

Deep inequality

Of course, Kenyan elections have often triggered clashes between tribes, as political parties tend to draw support from particular ethnic groups.

But Kenya's violent past interacts toxically with another contributing factor: Deep inequality, especially between different regions. It is that, rather than poverty, which sparks political violence and crime. Official unemployment hovers around the 40% mark, with young people the worst affected. Tribal rivalries can easily cause tensions to spill over.

Meanwhile, the political elite continue to award themselves higher salaries and perks - considered the highest, external - against a backdrop of increasing labour unrest and strikes by doctors and teachers.

Ethnic tensions have added an extra dimension to the struggle for power

One of the many shortcomings of Kenyan society since the electoral violence has been its failure to takes the effects of the fighting seriously enough. The sheer relief that accompanied the arrival of the peace pact gave way to an unspoken belief that all was now relatively calm.

The truth is that thousands of those internally displaced during the violence are still in makeshift camps, four years on.

During the post-election crisis, there was state-directed violence against civilians, fighting amongst various civilian factions, and uprisings against the state by civilians.

As a recent report concluded, Kenya has not yet healed. The report says both the victims and the perpetrators of violence are still trapped in the after-effects of the fighting, external, without undergoing a healing and reconciliation process.

The belated Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission, set up three years ago, has yet to release findings and recommendations, adding fuel to the widely-held belief that the coalition administration is not serious in bringing closure to the election's events.

Part of the reason for this could be that this time the stakes are even higher.

Scarred country

In March, Kenyans will vote for county governors and senators for the first time. More power will be up for grabs, this time at a local level. This could lead to intense competition and rivalry, raising the likelihood of more violence.

And back in the Tana, a new threat to peace is emerging. Investors, both Kenyan and foreign, are acquiring leases on vast tracts of land, external for large-scale crop cultivation for food and bio-fuels.

Deeply scarred and limping into new elections, Kenya could be showing symptoms of post-traumatic stress on a large scale.

And it won't take much to make things worse.

Gray Phombeah is a Kenyan writer and broadcaster.