Swedish journalists tell of time in Ethiopia jail

- Published

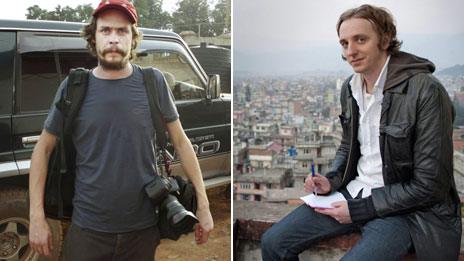

Martin Schibbye (L) and Johan Persson arrived back in Sweden in September after more than 400 days in an Ethiopian jail

Swedish journalists Johan Persson and Martin Schibbye have been speaking to the BBC about their time in prison in Ethiopia.

They were recently freed after serving more than 400 days of an 11-year sentence.

The pair were found guilty of entering the country illegally and supporting a rebel group, the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF).

Their lengthy jail terms put the treatment of journalists in Ethiopia under the international spotlight.

Martin Schibbye and Johan Persson were captured along with ONLF rebels in June 2011.

They maintained that they were only doing their jobs, and human rights group Amnesty International said the journalists had been prosecuted for doing "legitimate work".

But Ethiopian government spokesman Bereket Simon previously defended the decision to jail the pair, saying the journalists were caught "red handed" co-operating with "terrorist organisations".

Former Prime Minister Meles Zenawi reportedly pardoned the journalists before his death in August, leading to their release.

'Rats, fleas and sick people'

Johan Persson told the BBC World Service programme Newsday that conditions in the prison in which they were held were poor.

"It was 200% overcrowded. It was very hot. There was a lack of water. It was dusty. There were rats, fleas and many people were sick with HIV or tuberculosis," he said.

But he said the conditions were not as significant as the other inmates: "What's interesting is who they put in there: journalists and the political opposition."

Although the pair admit that they entered Ethiopia illegally, they argue that their trial was unfair.

"The trial was a joke," said Mr Persson. "Meles Zenawi was saying on national television, three or four weeks before the trial started, that we were guilty."

They also believe the charge of moral support for terrorism, of which they were found guilty, has been misused against other journalists in Ethiopia.

"For the last few years Ethiopia has been using its anti-terror legislation to crack down on the media and to crack down on journalism," Mr Schibbye told Newsday.

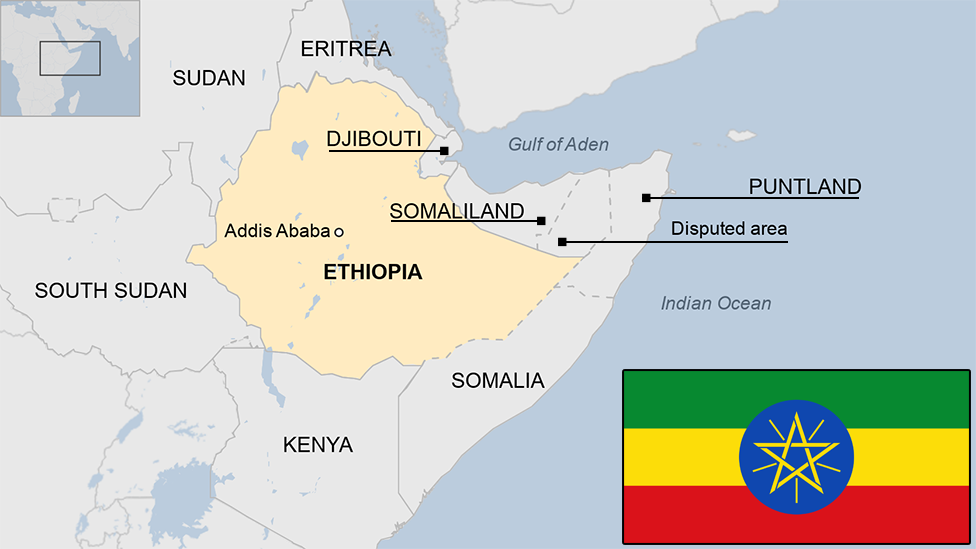

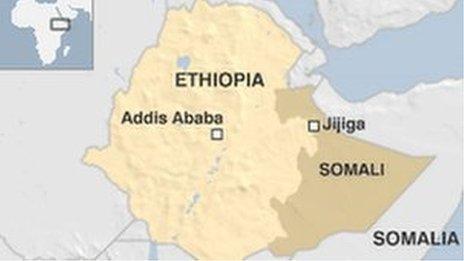

The freelance reporters had been in the Ogaden, an ethnic Somali region in eastern Ethiopia, for four days before they were arrested.

"The Ethiopian army spotted us. Then they followed in our footsteps for three to four days. Then they ambushed us.

"We were attacked by about 150 Ethiopian army soldiers who opened fire on us. We got hit quite quickly. I got hit in the shoulder and Johan got hit in the arm. Somebody shouted, 'media, media, international press,' and we were arrested," said Martin Schibbye.

'No regrets'

After their arrest they said they were ordered at gunpoint to take part in a film supposedly documenting their relationship with the Ogaden National Liberation Front.

"Two civilians, who we'd never seen before, were dressed up as rebels. The soldiers gave them guns and stood them in front of us, and they testified against us and said that we came with them from Somalia," says Mr Schibbye.

The journalists allege that senior Ethiopian civilian officials were in charge of the filming.

"This was not being done by some crazy militia: the director was the vice president in the region, and in the evening the regional president called us and said, 'We are not satisfied by your performances in the film,'" said Mr Schibbye. Eventually the film was used against them in court.

Ethiopia's eastern Ogaden region has been the focus of an insurgency by local ethnic Somalis.

"We were walking through villages where there had been people living till recently, but now they had fled, forced out by the conflict. There was heavy fighting and that was one of the reasons why we were detected and followed and ambushed by the Ethiopian army," Mr Persson said.

Despite spending more than a year in prison, they say they have no regrets their time in Ethiopia.

For Martin Schibbye, the work of foreign correspondent is one that requires taking risks and refusing to accept there are areas closed to journalists.

His colleague agrees: "As long as governments make laws to protect themselves against journalists, our job is to break those laws. I would do the same again today."

- Published11 September 2012

- Published30 June 2012

- Published13 July 2012

- Published22 June 2012

- Published2 January 2024