Ugandans evicted to make way for oil refinery

- Published

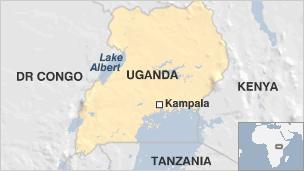

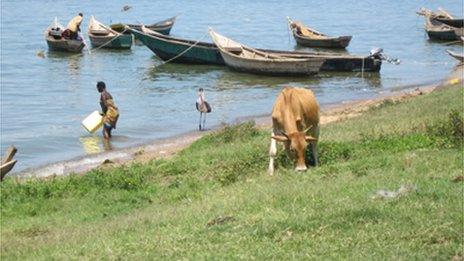

Jennifer Makune lives in Kabaale village not far from the shores of Lake Albert, one of the most visually stunning parts of Uganda.

The rolling hills and acres of lush green vegetation make it an awe-inspiring landscape.

Ms Makune's home, which is about 15 miles (24km) from the lake, is a thatched mud hut, where she lives with her five children.

Like thousands of other small farmers, she makes her living from farming her land, which is a 20-minute walk from her house.

But all of this is about to change because below the ground there is another treasure trove - oil.

This discovery is set to transform the lives of the people here - for better or worse.

The ministry of energy plans to build a refinery to process some of the oil Uganda will produce.

It has demarcated 29 square kilometres - the size of 3,500 football pitches - for the project, which will also include an airstrip, shopping malls and apartments.

Ms Makune's land is part of the earmarked area.

Altogether nearly 8,000 people will be evicted from their homes and farms to make way for the refinery.

Some will be relocated whilst others will be compensated.

Leaders grilled

The biggest concern for people like Ms Makune is whether the authorities will adequately compensate them for the property they will lose.

The atmosphere at village meetings over the evictions and compensation is often tense

She believes her land is 5 acres (2 hectares) but government surveyors say it is just half that size.

"My land was measured in my absence, it wasn't till later when I realised how much it had been underestimated. When I raised the issue, I was told they could not come back," she says.

Her neighbour agrees that Ms Makune's land was underestimated, saying the boundary was placed well into her farm, giving him a share of her property.

The Petroleum Exploration and Production Department (PEPD), the government body in charge of the refinery project, hopes to complete the first phase by 2015.

It has been holding public dialogue meetings with the people who will be evicted.

The one I attended in Kabaale was held under the shade of a tree protecting everyone from the scorching sun.

It was well attended; most seats were taken whilst others had to stand.

The atmosphere was intense and the local people were very vocal, grilling the PEPD's representatives and local leaders.

But it seemed they were resigned to their eviction and just wanted the best deal they could get, as compensation figures have not yet been set.

Gilbert Rubanga says the government should be more open in its dealings with the communities.

"My land is very productive but now I'm going to lose it by force. Because if the government says it wants your land, whether you like it or not, it is the government," he says.

"Land is not like bananas which you buy from the supermarket. It's something very important in this world.

"But before they have these meetings, they first sit in town; they discuss all the matters in town. Yet those who are affected - we are here."

A lot of people raised questions about whether the surveys were accurate.

Employment opportunities

PEPD communications manager Bashir Hangi believes the people in the area are getting their measurements wrong.

"Remember they are using traditional methods of looking at a piece of land and you estimate that this is three acres, this is five acres.

"Now when you bring survey equipment, we get different things because now the equipment we use gives us the exact size of the land.

"Some still don't believe that our tools are giving the right measurement so we're encouraging them to get independent surveyors."

Crude oil deposits have been found under Lake Albert

People like Ms Makune who cannot afford such an expense are left at a loss.

She is hoping her neighbour's testimony can convince the authorities to re-measure her land.

The government, however, is adamant that the refinery will be of great benefit to the people of Kabaale village, the surrounding area and country as a whole.

Its key argument is that Uganda cannot simply export raw materials, it needs to add value to the crude by refining it, before shipping it out.

"We are looking at the benefits of the refinery - first of all, it will boost employment," says Mr Hangi.

"There are other industries that go with refining like petrochemicals, which will add to the industrial base of the country.

"Another benefit will be security of petroleum products. Refining in-country will help overcome import bottlenecks.

"And then we will see an increased revenue base for the country.

The refinery may also be able to refine crude from eastern Democratic Republic of Congo and Tanzania should their oil deposits prove to be commercial, Mr Hangi says.

Too ambitious?

But the oil companies are not so sure.

For example, Tullow Oil believes the government's plan to create a refinery that processes 120,000 barrels of oil per day (bpd) for sale to regional markets is too ambitious.

This is more than half of the 200,000bpd Uganda is expected to produce when its oil sector is in full gear.

Aidan Heavey, the company's chief executive, is on record as saying that he does not think there will enough demand within East Africa and the Great Lakes region for the petrol produced in Uganda.

He thinks a refinery operating at half that capacity is more viable.

Tullow Oil and its partners in Uganda, Total and China National Offshore Oil Corporation, think a pipeline that moves the oil from the Lake Albert and other fields to the Indian Ocean via Kenya is the best way to get Uganda's crude to market.

Negotiations between the oil companies and government are still ongoing about how the oil refinery and pipeline can co-exist.

Despite these challenges the authorities here are pressing on with the project.

They will soon be looking for companies to help fund the refinery's construction.

Ms Makune welcomed the refinery when she first heard about it, as she thought it would create jobs and new sources of wealth for her and her neighbours.

All compensation is due to be paid by next June, but she believes it will make her poorer and she still does not know how she will make a living after her farm has been taken.

- Published4 November 2011

- Published9 November 2011

- Published26 April 2023