Cyril Ramaphosa - South African union leader, mine boss, president

- Published

With his suave, urbane demeanour, decades worth of political experience and significant role in the anti-apartheid movement, one would have expected Cyril Ramaphosa to confidently land a second term as South Africa's president.

But Mr Ramaphosa led his African National Congress (ANC) to its worst election result in 30 years - falling short of the 50% of votes needed to govern alone.

As a result of their dismal election performance in May, Mr Ramaphosa only survives as party leader and national president thanks to a power-sharing deal with the centre-right Democratic Alliance (DA) and two smaller parties.

The 71-year-old's first stint in office was blighted by stubbornly high unemployment, persisting economic inequalities, widespread power cuts and corruption allegations.

It is a far from ideal state of affairs, especially for a man said to have coveted the presidential role since the ANC came to power in 1994.

Born close to the centre of Johannesburg in 1952, Mr Ramaphosa experienced the injustices of the racist system of apartheid early.

His family were forcibly moved to the township of Soweto when he was just a young child - they were among the millions of black South Africans relocated to distant, often economically deprived reserves by the authorities.

As a secondary school pupil Mr Ramaphosa "took his school teachers to task if he didn't think they were working hard enough", his biographer Anthony Butler tells the BBC.

"He was very confident and popular," Prof Butler adds.

Mr Ramaphosa became involved in the black consciousness movement at university and as a result of his activism he endured two months-long stints in solitary confinement.

He crafted a reputation as a thorn in the side of white mine bosses in the 1980s, leading the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) in one of the largest strikes in South Africa's history.

He also joined the ANC and worked closely with Nelson Mandela to negotiate an end to minority rule, which came in 1994.

When Mr Mandela became South Africa's first black president, Mr Ramaphosa harboured ambitions to become his deputy.

However it was not to be - he was overlooked for the more senior Thabo Mbeki.

Dispirited, Mr Ramaphosa took up the role of MP and played a leading role in drafting South Africa's post-apartheid constitution, one of the most liberal in the world.

He later withdrew from the political centre-stage to become a business executive, despite being well-liked by the public.

Nelson Mandela (R) chose Thabo Mbeki (L) as his successor, rather than Mr Ramaphosa

"He was persuaded by Mandela and the others to take time out. He was a relatively young man," Prof Butler says.

As white businessmen tried to accommodate him, Mr Ramaphosa acquired a stake in nearly every key sector - from telecoms and the media to beverages and fast food (he owned the South African franchise of the US chain, McDonalds) to mining.

His ventures were wildly lucrative - by 2015 he had become one of South Africa's wealthiest politicians with a net worth of about $450m (£340m).

But Mr Ramaphosa's reputation was tainted after police killed 34 workers in August 2012 at the Marikana platinum mine - the most deadly police action since white-minority rule ended.

With Mr Ramaphosa then a director in Lonmin - the multinational that owns the mine - he was accused of betraying the workers he once fought for, especially after emails emerged showing he had called for action against the miners for engaging in "dastardly criminal acts" - an apparent reference to their wildcat and violent strike.

A judge-led inquiry cleared him of involvement in the killings, but failed to totally scrub the stain from his legacy.

The unionist turned tycoon had just started his political comeback, after being chosen as the ANC's deputy leader.

Two years later, he became South Africa's deputy president, giving legitimacy to the scandal-hit presidency of Jacob Zuma.

But as Mr Zuma neared his two-term limit as ANC leader, Mr Ramaphosa entered the succession battle, positioning himself as the anti-Zuma candidate.

His pledges to fight corruption were widely seen as a dig at the man who remained his boss at the national level.

Mr Ramaphosa was the natural favourite for the top job, but the then president threw his weight behind his ex-wife and former African Union Commission chief, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma.

A bitter contest ensued, with Mr Ramaphosa eventually beating Ms Dlamini-Zuma to become ANC leader in December 2017.

Mr Zuma intended to stay on as South Africa's president until the 2019 general election. But following intense pressure from ANC leaders - including Mr Ramaphosa - the embattled president was forced to resign.

After almost 25 years Mr Ramaphosa's long-held dream was realised - MPs broke into song in parliament when it was announced he would succeed Mr Zuma as president of South Africa.

The new leader used his initial speech to make a stand against corruption - but shortly afterwards became embroiled in a series of of his own scandals.

In 2018, Mr Ramaphosa told parliament he had not received campaign donations from a controversial local company during his ANC leadership bid.

He later apologised, saying he had been misinformed when he gave the answer.

This admission undermined Mr Ramphosa's own anti-corruption drive but years later the High Court dismissed the notion that he deliberately misled parliament.

In 2022, a long-awaited inquiry laid bare the looting of billions of dollars from South Africa's state coffers during Mr Zuma's presidency.

Mr Ramaphosa was implicated in the findings, with investigators concluding he should have done more to stop the rot while he was Mr Zuma's deputy.

And just a few months later, before the dust had settled from that inquiry, Mr Ramaphosa became the focus of another corruption scandal.

In June, the president was accused of hiding a theft of $4m (£3.25m) in cash from his Phala Phala game farm.

While denying any wrongdoing, the president admitted that money hidden in his sofa had been stolen in 2020.

He said the cash totalled $580,000 (£460,000), not $4m, and that he had earned the $580,000 by selling buffalo. An independent panel of legal experts, headed by a former chief justice, said it had "substantial doubt" about whether such a sale actually took place.

His opponents - both inside and outside the ANC - called for him to resign over "Farmgate" while parliament weighed up whether or not to launch impeachment proceedings.

But the president ultimately won the backing of the ANC's leaders and stayed on in the top job.

"He rode that out quite effectively," says Paddy Harper, a journalist with South Africa's Mail & Guardian newspaper, adding that the major criticisms of Mr Ramaphosa's first term were issues like the water crisis, load shedding and unemployment".

The ANC's popularity certainly suffered because of these issues, but political analyst Richard Calland tells the BBC Mr Ramaphosa has been a "steady, if not spectacular" president who inherited unfavourable conditions from the previous government.

"I think that he has been the leader we needed and the best available leader, despite his weaknesses, despite the fact that many of the metrics around the recovery of the economy and so on are still negative," he says.

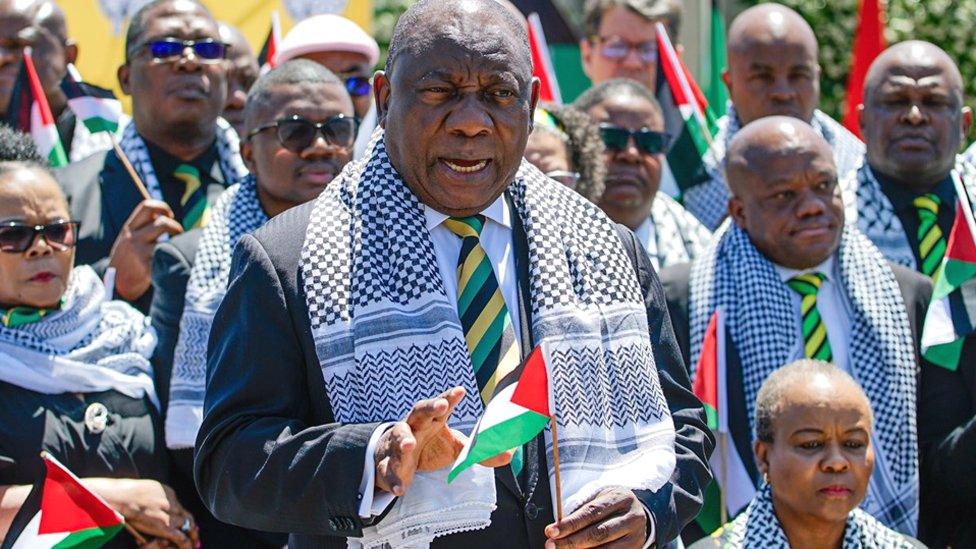

Mr Ramaphosa has been a vocal critic of Israel's war in Gaza

Under Mr Ramaphosa, South Africa has emphasised its credentials as a champion of the global south, most notably in the way that it has led the condemnation of Israel over its war in Gaza. This culminated in South Africa taking Israel to the International Court of Justice in The Hague, accusing it of genocide.

It is also a leading voice in the Brics grouping of countries, seen as an alternative to the more Western-oriented G7.

South Africa has refused to condemn Russia over its invasion of Ukraine, straining relations with the US. The president led a delegation of African heads of state to both Kyiv and Moscow in an ultimately fruitless attempt to broker a peace deal.

In 2019 the president was praised for appointing a new cabinet in which, for the first time in the country's history, half of all ministers were women.

From trade unionist to leader of one of Africa's biggest economies, Mr Ramaphosa's career has been a catalogue of contradictions, history-making moments and fierce battles.

He now has yet another huge challenge on his hands. If the deal with his former enemies in the DA succeeds in turning round South Africa's moribund economy and creating jobs for the millions who need them, he will be remembered as the man who saved his country, and party.

But if not, even more South Africans will be tempted to back his arch-rival - Jacob Zuma and his uMkhonto weSizwe (MK) party.