Why the Sahara is not the 'new Afghanistan'

- Published

The brazen attack on a desert gas plant in Algeria last month and the French-led campaign against Islamists in northern Mali have triggered stark warnings in the West of a new front opening in the campaign to combat Islamist extremists but there is a danger of exaggerating the threat, analysts say.

US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton spoke of the need to prevent northern Mali becoming a "safe haven" from which militants could launch attacks against America.

British Prime Minister David Cameron said this "global threat" required a response that would take "years, even decades".

"Just as we had to deal with that in Pakistan and in Afghanistan so the world needs to come together to deal with this threat in North Africa," he said.

But militancy in the Sahara and Sahel, which stretches across the desert regions of Mali, Algeria, Libya, Niger and Mauritania, is tied to local dynamics and plays on local grievances and it would be a mistake to see all of the region's numerous armed groups as always acting in unison.

The only clear parallel with the border area between Afghanistan and Pakistan where the Taliban have flourished, analysts say, is the absence of central governments, which are unable or unwilling to counter extremism.

This is a long-standing problem in northern Mali. It emerged more recently in North African countries that saw Arab Spring uprisings, including Libya and Tunisia, allowing militant groups to gain ground.

"Right now we're not seeing as much an uptick in the strength of these groups as much as we are new areas that they're able to operate in because of the weakening of states," said William Lawrence, North Africa director for International Crisis Group.

"That's the major change in the last two years."

Kidnappings

The most prominent militant group in North Africa is al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), formed from the remnants of the Islamist insurgency in Algeria.

Its leaders have increasingly aligned themselves with international jihad (holy war), adopting the al-Qaeda name in 2007.

In the desert over the past ten years they have raised their profile - and tens if not hundreds of millions of dollars in ransom money - by taking westerners hostage.

Robert Fowler, a Canadian former UN diplomat kidnapped in Niger in 2008, has described the professionalism and apparent religious fervour of the men who abducted him.

"Their every act was considered and needed to be justifiable in terms of their chosen path of jihad," he wrote in his book, A Season in Hell.

The kidnappers were led by Mokhtar Belmokhtar, who more recently formed the AQIM splinter group, the Signed-in-Blood Battalion, blamed for January's attack on the Algerian gas plant of In Amenas.

Two other groups, Ansar Dine - dominated by former Tuareg rebels - and the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (Mujao), took control of northern Mali's major towns and cities following a coup in the capital, Bamako, last March.

They destroyed shrines sacred to Sufi Muslims and applied a radical version of Sharia law, chopping off the hands of thieves, authorising the stoning of adulterers, and forcing women to wear veils.

The Associated Press reported in December that they had set up bases in the desert north of Kidal, using heavy machinery to dig a network of tunnels, trenches and ramparts.

Social climbing

But for many observers, the behaviour of militants across the region is driven more by opportunism than any long-term adherence to a strict ideology.

In northern Mali they have exploited a history of separatism, armed conflict, Islamism and illegal trafficking going back several decades.

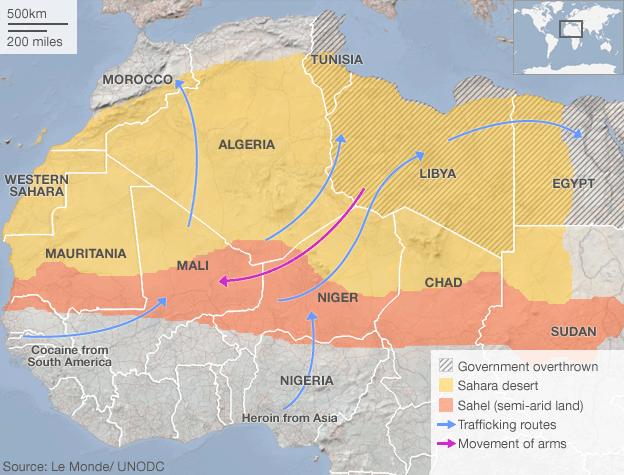

Goods smuggled across the Sahel's porous borders include everything from basic foodstuffs to petrol, cigarettes and cocaine.

Local authorities are often involved in such trade, a reason for collusion with smugglers and armed groups.

Many living in the area have complained of economic and political exclusion.

"The key elements were ones of development, poverty, institutional chaos, a power vacuum over this vast area, artificial borders, ethnic tensions," said Imad Mesdoua, a political analyst at Pasco Risk Management.

"The post-colonial structural problems of these countries have yet to be resolved."

Judith Scheele, a social anthropologist at All Souls, Oxford, who has spent time in northern Mali, said gaining access to weapons and raising your social status were also possible incentives for new recruits.

"If you're a young Malian now and you want to kidnap somebody, your best bet is to stick on the al-Qaeda logo, and it doesn't necessarily imply terribly much," she said.

Social life in northern Mali is largely structured on hierarchies derived from descent. Some historically low-status people have recently grown rich through smuggling and trade, and since religious practice is also an important marker, may have joined extremist groups to raise their status.

"This is an area where being connected to any kind of religious movement or family is a way to be socially mobile," Ms Scheele said.

'Self-fulfilling prophecy'

Such allegiances can be confirmed in marriage, as they were in the case of Algerian militants who have settled in northern Mali and married locals.

But they can also change, or be combined with other allegiances.

The same goes for armed groups, which have a record of shifting their goals, splintering, trading with each other, and competing - sometimes encouraged by local intelligence services.

The Islamists formed a broad and loose coalition in northern Mali, but only after they had allied with, and then turned against, the Tuareg separatists of National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA).

Ansar Dine is led by the former Tuareg rebel leader, Iyad Ag Ghaly, known for manoeuvring himself into positions of influence under various guises.

Shortly after French forces invaded last month, a faction called the Islamic Movement for Azawad said it was splitting from Ansar Dine, and rejecting "all forms of extremism and terrorism".

The In Amenas attack was widely seen as an attempt by the Signed-in-Blood Battalion to make its mark in Algeria, where the security forces have long had Islamist militants onto the back foot.

Atmane Tazaghart, author of a book on AQIM, says there are an estimated 1,200-1,500 Islamist fighters currently in the Sahel. But he added that it was "hard to distinguish banditry in this region from the jihadi activity".

Against this backdrop of blurred identities and complex motives, William Lawrence of International Crisis Group warned against heavy-handed, indiscriminate intervention to counter the perceived Islamist threat, which might be encouraged by thinking of the Sahel as a "new Afghanistan".

"The only risk in terms of the comparison is of a self-fulfilling prophecy," he said.

"Tactics and methods applied in Afghanistan and Pakistan, if employed in this region, could engender resentment and further radicalisation."

Following the recent attack on an Algerian gas plant, UK Prime Minister David Cameron says that the Sahara desert has turned into a haven for militant Islamists who are waging a jihad against the West. He says it will take decades to defeat them. What is the background to this growing threat?

The Sahara used to be a thriving economic zone, famed for its long camel caravans laden with salt, which in the Middle Ages was said to be worth more than gold. But times - and trade routes - have changed and now the countries on the desert's southern fringes, mainly ex-French colonies, are among the world's poorest.

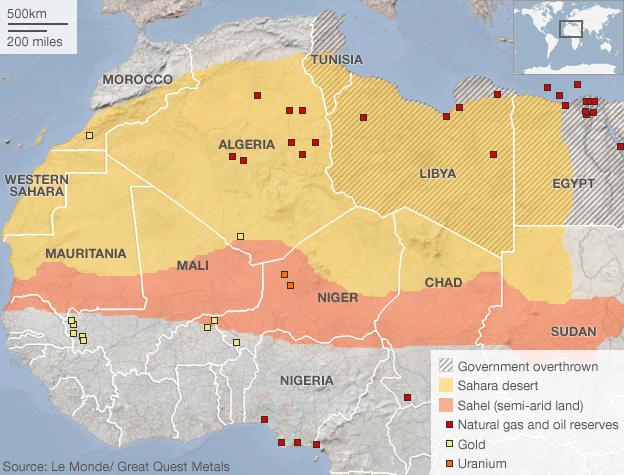

Although most of the desert's inhabitants are poor, there are rich natural resources to be found under the sands. Algeria has oil and gas, Niger has one of the world's largest uranium reserves, which power France's nuclear plants. Mali is Africa's third biggest gold producer.

Some of the region's inhabitants have used their desert knowledge for criminal purposes - smuggling migrants and drugs along ancient routes to Europe. Some jihadists have used the profits to buy arms. When Col Gaddafi was toppled in Libya in 2011, many Tuareg fighters returned to Mali and started a rebellion.

The Tuareg rebels joined forces with Islamists who had been expelled from Algeria in the 1990s and had spread across the Sahara, forging links with al-Qaeda and staging attacks in all of the region's countries. In April 2012, the new alliance quickly seized northern Mali - an area larger than France.

Numerous armed groups operate in the Sahara - with a mix of motivations from making money, to self-rule to global jihad. It is hard to know to what extent they work together. There are reports that other militant groups such as Nigeria's Boko Haram and Somalia's al-Shabab have links to the Saharan jihadists.

The militants who attacked the gas facility in Algeria are said to have been from countries across the region. Many Saharans share strong family and cultural ties with residents of the desert in other countries and see the desert as a single vast area rather than parts of several different national territories.

- Published12 March 2013

- Published21 January 2013

- Published20 January 2013

- Published24 January 2013