Why African art is the next big thing

- Published

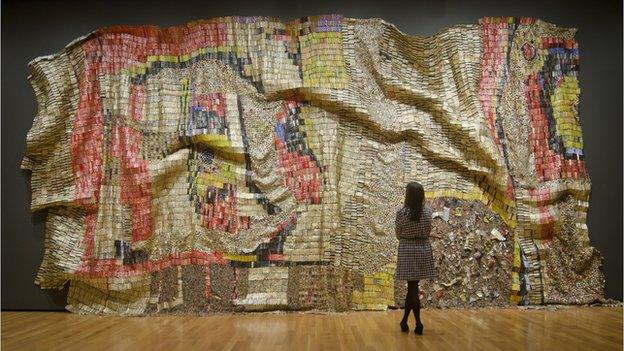

Earth’s Skin by El Anatsui is among the pieces on display at the Brooklyn Museum in New York

With major museums in London and New York showcasing leading contemporary African artists this summer, and Angola's recent success at the Biennale in Venice, is the world of art finally putting Africa on its map?

Ghanaian sculptor El Anatsui is among the most celebrated contemporary African artists at the moment.

Among his most iconic pieces are sculptures made from thousands of bottle tops, strung together with copper wire to form enormous shimmering sheets, which undulate and fold into different shapes.

Mr Anatsui's installations are currently on display at the Brooklyn Museum of Art in New York - one of the few solo exhibitions of an African artist at a big institution in the United States in the last few decades.

"El Anatsui's career has taken on a meteoric rise," says Kevin Dumouchelle the curator of the exhibition.

"At the beginning he was regarded as the best contemporary artist in Africa, but he made a leap and has become a global artist."

Growing interest

Mr Dumouchelle acknowledges that most visitors are rather surprised when they see who is on display.

"There is definitely a sense of catching up," he says.

And Mr Anatsui is not only being celebrated in New York, but also across the Atlantic in the UK.

A Vision of the Tomb by Sudanese politician turned painter Ibrahim El-Salahi

Following an invitation from the Royal Academy in London, he has created a large wall-hanging sculpture for the duration of this year's summer exhibition.

The installation in London coincides with several exhibitions this summer of other contemporary African artists at Tate Modern - one of the leading contemporary art museums in the world.

The museum is preparing for the first major retrospective of Sudanese painter Ibrahim El-Salahi, as well as a special installation of the works of Meschac Gaba from Benin.

Tate acquired Mr Gaba's work as part of its drive to expand their existing collection with pieces by African artists.

"Historically Tate's international collection concentrated on art from Western Europe and North America," says Kerryn Greenberg, one of the curators at Tate specialising in art from Africa.

She says the new acquisitions acknowledge that some of the most dynamic and important works of art are being created in Africa.

"There does appear to be a growing interest in African art, especially in the UK. African artists are becoming increasingly mobile and visible and exhibiting internationally."

Breakthrough

Tate's decision to expand their collection of African art was noted among curators as well as private collectors, and is widely seen to have contributed substantially to the current buzz about African art.

Bonhams in London is the only auction house with an annual sale dedicated to contemporary African art - the first auction was five years ago.

"After years of having to push at closed doors, the recent sale in May felt like a breakthrough," says Giles Peppiatt, director of Bonhams' African Art department.

According to Mr Peppiatt there was a lot of interest from museums and private buyers in Europe and the United States, but also from Africa, especially Nigeria.

"People are much more interested in Africa commercially. The continent is seen as the next big thing, and there is an enormous amount of wealth among Africans."

Compared to contemporary art from other parts of the world, the prices for African art are still quite modest, and investors are seeing it increasingly as a good investment.

Flag by Meschac Gaba will be on display at Tate Modern from July

"Public museums don't have lots of money, so their curators have to look over the hill and see what might be the next big thing," says Mr Peppiatt.

Africa's increasing presence on the international art market helped Koyo Kouoh - a Cameroonian-born curator - to secure funding for the first contemporary fair for African art in London later this year.

She says the idea has been in the pipeline for years, but the increased focus on African art internationally and the increased prominence of African art professionals made all the difference.

Huge surprise

"We have corporate sponsors from Africa as well as philanthropic funding from Europe. Everything is coming together."

Ms Kouoh has just returned from the Venice Biennale - one the world's most important events for international contemporary art.

A record number of African countries are represented at the biennale this year and Angola managed to secure the award for the best national pavilion, the first African country to ever win the prize.

"It changes the perception of Angola. The focus is not just on war anymore," she says.

"The award is praise for Angola but also for Africa. African countries are getting more and more involved in promoting art and they are using art to promote their country."

Works by Edson Chagas, a 36-year-old photographer based in Luanda, were the pavilion's showpiece.

"It was a huge surprise," says Mr Chagas, "especially because it was the first time we were participating."

Born in Angola during the civil war, he was sent abroad by his parents when he was 15.

Edson Chagas believes his award will spark interest in works by other contemporary Angolan artists

Later on he studied photography in Europe - in the UK as well as in Portugal.

"There was no art school in my country so I decided to go to London. But my goal was always to come back to Angola," says Mr Chagas.

"I really believe that after winning this award there will be more interest in my work and the works of other contemporary artists from Angola."

Mr Chagas also hopes that the international recognition will prompt the government to use some of the country's petrodollars to fund the next generation of Angolan artists, so that they can be educated in the country.

"Bursaries are the first step, but we also need money to create spaces so we can reflect on our country and its history."

Until recently many African artists struggled to secure funding and recognition, but with the buzz about contemporary African art among museums and private collectors, Mr Chagas and fellow artists might finally be lucky.

Giles Peppiat was interviewed on the BBC World Service.

- Published6 June 2013

- Published16 April 2013

- Published27 November 2012

- Published18 June 2013