Nelson Mandela's illness: Defending his dignity

- Published

If you want to know about the health of South Africa's first black President Nelson Mandela there is really only one person to call - and it is not some junior spokesman in the presidential bureaucracy.

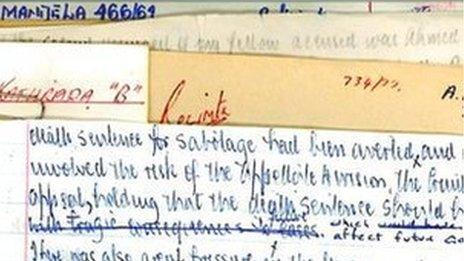

Instead, it is one of Mr Mandela's oldest, closest friends - a silver-haired, razor-sharp, 78-year-old South African called Mac Maharaj, who spent years imprisoned on Robben Island with Mr Mandela, and even transcribed and smuggled out a draft of his autobiography, Long Walk To Freedom.

Mr Mandela, 94, once described him as "the cleverest chap I've ever met".

As you can imagine, the calls have been coming in thick and fast these days, with the world's media anxious to keep up with what little information is being released about Mr Mandela's health.

Mr Maharaj - the official presidential spokesman - may not always pick up, but when he does, he remains courteous, canny and - the hallmark of his generation of cadres of the governing African National Congress (ANC), which fought racial oppression in South Africa - resolutely devoted to the party line.

His role is an important daily reminder that Mr Mandela's failing health is an intensely personal issue for many of those now involved in the distressing task of managing the flow of information from a Pretoria hospital bed, to a waiting world.

Mandela's writings were transcribed by Mahararaj behind bars (National Archives of South Africa, courtesy NMF)

Outside the hospital, a large scrum of local and international journalists remains camped out in the bright, cold winter weather.

'Extraordinary life'

It is a hard story to get right.

Journalistic instincts require that we should push for all the information we can get, and be alive to the possibility of being misled by a presidential administration that is, on a multitude of other issues, routinely suspected of cover-ups.

A couple of years ago, when Mr Mandela's long-standing health problems suddenly became a more urgent concern, the official instinct was to clam up, say nothing, and on occasion even mislead the crowds waiting outside hospital.

Journalists reacted with outrage.

I remember accusing the head of the Nelson Mandela Foundation of being "disingenuous". I squirm at the memory now.

What many of us interpreted then as stonewalling or evasion was, it strikes me now, the natural, protective reaction of a group of people so close to Mr Mandela that their instinct was - and still is - to defend his dignity above all.

Today, most of us have learned our lessons.

We do not want to be lied to, but neither do we expect to be given private medical information.

And so, when a US television network boldly declared this week that it had confirmed information about the state of Mr Mandela's internal organs, we shook our heads, declined to re-Tweet, and understood the genuine, bitter fury of Mr Maharaj.

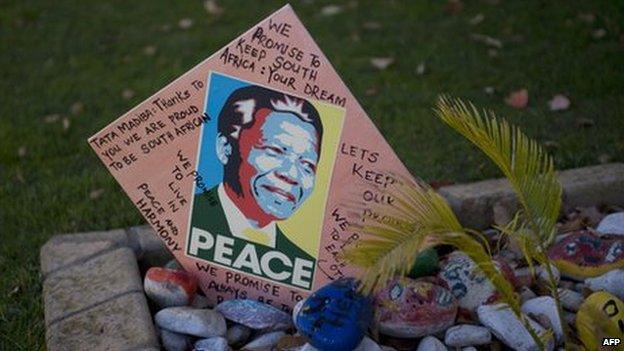

Mr Mandela will not live forever.

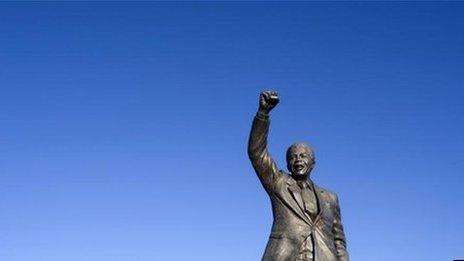

When he dies the world's media will try to capture the reactions of people here and around the world, and, in retelling his extraordinary life story, try to do justice to the memory of the man.

I suspect we shall all fail to live up to the magnitude of the moment.

But we will try our best.

- Published10 June 2013

- Published8 June 2013