Can South Africa avoid doing a Zimbabwe on land?

- Published

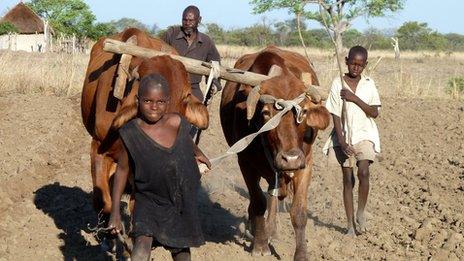

More than eight million South Africans depend on agriculture for their livelihoods

Land reform is a thorny issue in South Africa; for some it conjures up images of Zimbabwe-like land grabs and raises tensions in small farming communities.

The 1913 Natives Land Act divided the country into white and black areas and a century later, most of the country's best land remains in the hands of a few thousand white commercial farmers, while tens of thousands of black peasants are crammed together in less fertile areas.

While some fear this powderkeg could explode, the sugarcane industry seems to be proving that reform can happen amicably.

Fifth-generation sugarcane farmer Alan Bruscow has been training his new neighbours, a group of 36 black farmers who were awarded a farm through the land reform policy four years ago.

The two farms, the Bruscow farm and the Zibophezele farm, outside Pietermaritzburg in KwaZulu-Natal are about 50m (164ft) apart.

There is nothing separating them - if you didn't know you would think it is all one big farm.

Mr Bruscow describes his relationship with the black farmers as one of "trust and working together". It is a rare but admirable sight.

"I'd say that trust is a key element here and you build trust by working with people," says Mr Bruscow.

"They need to see that you're for them and they are for you, and you are there to try and make them as successful as possible and vice versa."

Set to fail?

One of the main problems with South Africa's land reform so far, experts say, is a lack of capital to sustain the farms under new ownership.

Sipho Xulu says it is important to pass on his land to his children

The other is that many of the black farmers who win land claims have no skills to run a farm, let alone turn it into a successful business - these farms end up unproductive.

A study presented at the Land Divided conference in March, external showed that many land transfer projects were failures.

Peter Jacobs of the Human Sciences Research Council reported that only 167 land-reform beneficiaries from a sample of 301 farms were actively farming. And many of them used only a small piece of their land for agricultural activities.

But this is not the case on the Zibophezele farm, where Sipho Xulu is working his land with a tractor in preparation for this season's harvest.

Being a landowner has given him a sense of security.

"Land is extremely important - there is virtually nothing one can do without it. We live off the land - our children will also benefit from it. It has given me a real chance to leave a legacy for my family," he explains.

Mr Xulu says the mentorship he has received has been invaluable.

"There is a lot of suspicion about white farmers in this part of the world but our mentor has proven to be a good man - we wouldn't be where we are without his teachings," explains Mr Xulu.

Land or cash?

In South Africa, agriculture, land and labour are closely entwined.

The South African Sugarcane Association (Sasa) says the only way of securing the future of this industry is through partnerships between new and old farmers.

This is why Sasa took the pioneering decision to set up its own land reform unit.

"Unless both black and white farmers commercial farmers cross that barrier and understand that we need one another for our mutual successful and for the benefit of the country, we won't get very far," says Sasa land reform unit head Anhwar Madhanpal.

Of South Africa's 1,500 commercial sugar farms, about 300 are now black-owned and most are said to be doing well.

South Africa's land reform programme is divided into four pillars: Redistribution, restitution, development and tenure, according to Land Reform and Rural Development Minister Gugile Nkwinti.

The emphasis so far has been on redistribution - buying land from white owners and redistributing it to black people whose families were forced off it during white minority rule.

But Mr Nkwinti says more people have opted for restitution - cash payments - than having their land back.

The government says that in today's increasingly urbanised South Africa, choosing a financial settlement this "is a reflection of poverty, unemployment, and income want".

Nineteen years after the end of apartheid, there are no official figures on what proportion of land is white-owned.

Mr Nkwinti said his department is now working on getting a breakdown of private land ownership according to race and even nationality.

Racial tensions

Despite the progress made in the sugarcane industry, the government has had to concede that it will not meet its target of transferring 30% of South Africa's land to black hands by 2014.

Sugarcane farming is one of the main industries in KwaZulu-Natal

To date less than 10% of white-owned land has been handed over, with the delays blamed on the government's "willing buyer, willing seller" policy, under which white farmers are not compelled to sell their land.

"This policy has so far allowed property owners to block redistribution efforts, as it allows property owners to refuse to have their property expropriated and also allows them to hold the government to ransom by demanding that the state pay exorbitant prices for property intended for expropriation," says constitutional expert Pierre de Vos.

In the face of the lack of progress, some activists are calling for a more drastic approach, including taking land from white farmers without compensation - something which the South African constitution makes provision for.

But many look at Zimbabwe's economic meltdown after it seized most of the country's white-owned commercial farms and caution against this approach.

Some 8.5 million South Africans depend directly or indirectly on agriculture for their livelihood.

"We have to co-operate because finding a solution is for the benefit of all South Africans, black and white," former ANC Chief Whip Mathole Motsekga told parliament recently.

"We can't guarantee peace in this country unless we find an equitable solution."

Mr Xulu and Mr Bruscow hope their model can be copied across the country to prevent the situation coming to that.

"It's about thinking of the future," says Mr Bruscow.

"A government settlement is temporary but the relationships you can build with people are forever. Our children will grow up to run these farms one day and we owe it to them to make sure that they are around for them."

- Published2 July 2012

- Published1 December 2011

- Published9 July 2024