In pictures: Surviving Central African Republic anarchy

- Published

Chimene Kpakanale, 22, is considered one of the luckiest mothers in the Central African Republic (CAR) as she has been able to have her third child, a baby boy, safely in a hospital. Other mothers have been forced to flee their homes, because of fighting and the fall-out following the rebel takeover in March, and have to give birth in the bush with no shelter or skilled help on hand.

At the best of times CAR has one of the world’s highest rates of infant deaths and one in 10 babies do not live to see their first birthday. Now the UN says the country has the potential to become a failed state following “a total breakdown in law and order” since the rebellion by the Seleka alliance which ousted President Francoise Bozize.

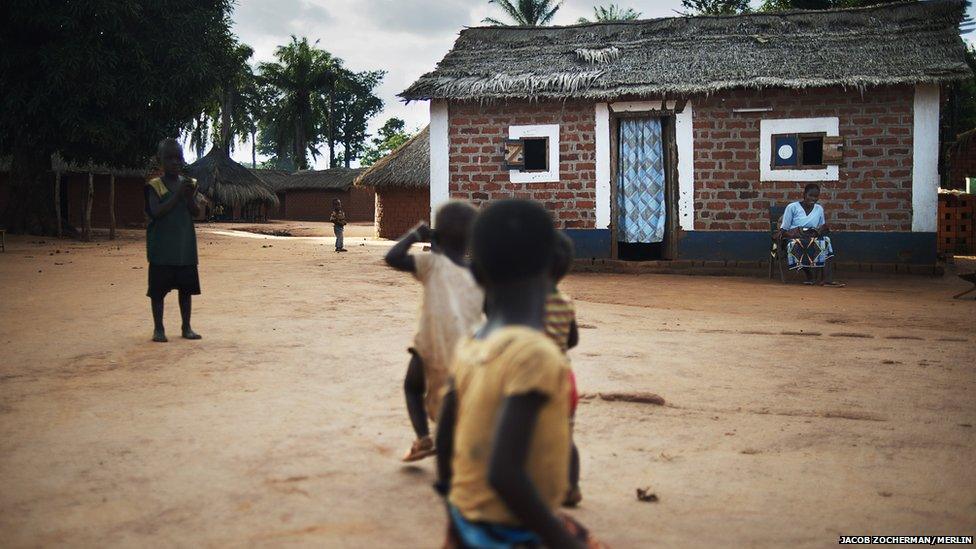

Ms Kpakanale, her husband and three children live in Obo, a stronghold of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), led by Joseph Kony. Years of unrest in the CAR have allowed the Ugandan rebel group to set up bases in the area. She says life in the small town is difficult - more so since March when LRA fighters intensified their attacks. Their presence has isolated Obo from the rest of the country because nobody dares to travel by road any more.

With more and more people arriving in Obo, about 900km (about 560 miles) east of the capital, Bangui, fleeing unrest elsewhere, resources have become very stretched in the town. Once there people are too scared to leave, so the town's expanding population has to grow crops on limited land. For Ms Kpakanale and most other families in Obo, this means less money and less to eat.

In the south-west of the country, food prices are soaring and malnutrition is also increasing, particularly in Batalimo town, a three-hour, 70km drive from the capital. Anatole Nzu, 32, is a nurse at a refugee camp in Batalimo set up for those fleeing violence over the border in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The camp’s hospital, which also serves the local community, cared for many people wounded in the aftermath of the Seleka rebellion.

Looting and banditry forced many, including most aid workers and local health ministry staff, to flee. But Mr Nzu remained, working 14 hours a day to treat injuries and provide basic healthcare to constantly increasing numbers of patients. The hospital staff worked entirely cut off from the outside world - phone coverage is extremely poor and internet access next to nothing. One patient said she spent three weeks in the bush with her two children after “uncontrolled soldiers entered the camps with their guns”.

At one stage there were only enough drugs to last for another 75 days and security was so volatile that all of the vehicles belonging to the aid agency Merlin, which set up the hospital, had to be taken to neighbouring DR Congo. “Although I’m from DR Congo, all people here are my brothers and sisters so I’m grateful for the work I can do here to help,” Mr Nzu said.

Nearly six months on from the rebel takeover, Mr Nzu is greeted in the morning when he arrives at work by long queues of people waiting outside the hospital gates – an hour before they open. Refugees and people from the local community sit together and wait. Most need treatment for malaria, diarrhoea or respiratory diseases. All of these illnesses are treatable but can be life-threatening without medical care.

Mr Nzu, who arrived in Batalimo from DR Congo in 2009, fleeing violence in his village, considers himself lucky as he is able to provide for his family including his wife and six children. When he first came to Batalimo the area was just bush land – now, small mud houses cover a huge area which is home to 6,000 refugees. The UN Security Council has warned that the current trouble in CAR poses a "serious threat" to regional stability in an already volatile area.

About a third of CAR’s 4.6 million people need assistance with food, shelter, health care or water, the UN’s humanitarian chief Valerie Amos has said. Many families eat cassava, a root vegetable, at every meal and nothing else. Although it fills the stomach, it is not nutritional. Many children end up with kwashiorkor, an acute form of childhood malnutrition which is characterised by a swollen belly and can lead to acute fluid retention and serious organ damage.

Merlin is concerned that infant mortality could triple in parts of the country as a direct result of the humanitarian crisis, which has left 3.2 million people without access to health services following the rebel takeover. Unpaid Seleka rebels, with no chain of command, continue to sustain themselves with looting and crime. UN officials have now called for greater support for a 3000-strong peacekeeping force assembled by the African Union.

Ms Kpakanale gave birth to her boy at 21:00 on 17 July, and before leaving the hospital in Obo he was vaccinated against tuberculosis and polio. Many other hospitals and health facilities have not been spared the looting and many vaccination efforts have ground to a halt. As a result measles and tetanus are spreading at alarming rates. (Photos by Jacob Zocherman working for aid agency Merlin)