Can democracy deliver for Africa?

- Published

- comments

Swaziland recently held elections without political parties

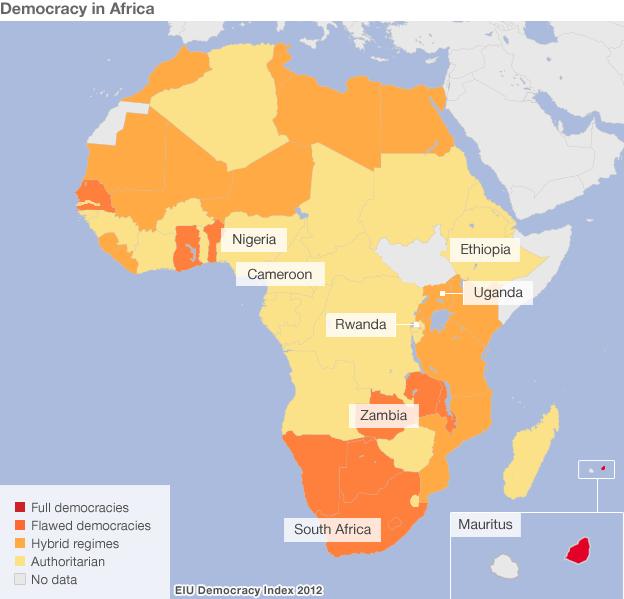

Multiparty democracy swept across Africa in the early 1990s, as single-party states and authoritarian leaders bowed to pressure from outside and within. Activists hoped greater political freedoms and strong institutions would lead to more government accountability - and more effective development. But two decades later, is this the reality?

Pallo Jordan is a member of South Africa's governing African National Congress (ANC) and was part of the first cabinet in 1994. For him, there is no denying that they are better off with democracy.

"We have made tremendous progress in this country, with respect to everything. Just the most basic things like the right of the governed to choose their own government."

It is what people fought for, in South Africa and across the continent. But not everyone is happy with the outcome.

Even within South Africa, many feel marginalised in the new democracy.

Economically, South Africa is still one of the most unequal societies in the world. The same party has been in power since the beginning of multi-party democracy, and that does not look like changing any time soon.

There is also a difference between democracy in theory and democracy in practice.

Is Uganda a democracy?

Uganda is officially a multiparty democracy. Its President, Yoweri Museveni, has been in power since 1986, and oversaw the transition from a single-party to multi-party state.

Yet many complain that democracy there is a mirage.

Arthur Arok, Uganda director of the international development charity ActionAid and an outspoken activist, says: "Opposition and civil society are seen as anti-progress and enemies of development. There is little space for real debate - and that goes against the spirit of democracy."

Mr Arok was arrested and detained back in January as part of the Black Monday movement against corruption, and questions the reality of democracy in his country.

"Is Uganda democratic? No, it's quasi-democratic, still under construction. There has been some improvement but the ruling elite are not really interested in democracy, they only want to entrench their own interests."

President Museveni has won four elections, changing the constitution to allow himself an unlimited number of terms. The most recent polls were deemed by European Union observers to be highly compromised.

Chris Zumani Zimba, author of Democracy Under Attack, describes Mr Museveni as one of a new group of "perpetual democratic leaders".

"Democracy is often undermined by leaders themselves, who are elected to office but then try to consolidate their power and make themselves more permanent," he says.

Cameroon's President Paul Biya has also removed term limits - and former Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo unsuccessfully tried to do the same.

Holding on to power

Another threat to democracy in Africa is seen to come from those who fought for it in the first place.

Wallace Chuma, a former Zimbabwean newspaper editor and now an academic at the University of Cape Town, says there is a familiar pattern of former liberation movements in government.

"They failed to tolerate internal processes of democracy. I think they have become hostage to their own successes as liberation movements. The tendency is to be closed to the outside and closed also to fresh ideas.

"If you look at the rhetoric from Angola to Mozambique to South Africa to Zimbabwe, you get the sense that any criticism against liberation movements in government is considered as being a traitor."

There is some debate as to what constitutes democracy, anyway. Even when elections are deemed to be free and fair - what happens in the period between ballots?

Corruption and impunity at the highest level are a sign that the balance of power still sits firmly with those in office - and not those who vote them in.

According to the African Union, more than $148bn (£93bn) is lost to corruption in Africa every year - much of it through public officials employed by democratically elected governments.

Poverty and underdevelopment can also be seen as a challenge to democracy, with a hungry and poorly educated electorate easily bought by politicians welding gifts and promises.

Indeed, some argue that democracy is not the most stable base for economic development anyway.

Alex Ngoma, a political scientist at the University of Zambia, points to the Asian Tigers' example, "where democracy is less of a priority and they waste less time talking - but get economic results. It's proof that there is more than one way to get things done."

China is consistently ranked as one of the fastest growing - and most powerful - economies on earth. Within Africa, Ethiopia and Rwanda are among the most successful - their growth built on a model of strong central government and limited political freedoms.

How to 'Africanise' democracy

Speaking this year on the death of Ethiopia's Prime Minister Meles Zenawi, Rwanda's President Paul Kagame was clear about both countries' lukewarm relationship with a Western version of democracy.

"Invariably, the question has been raised about whether the emphasis on development and the role of the state in it is not done at the expense of democracy and people's rights.

"Those who disagree with or criticise our development and governance options do not provide any suitable or better alternatives. All they do is repeat abstract concepts like freedom and democracy as if doing that alone would improve the human condition. Yet for us, the evidence of results from our choices is the most significant thing."

President Kagame is not alone in questioning multi-party democracy in the African context. Indeed, US historian William Blum in a recent book describes democracy as a Western imposition on Africa - "America's deadliest export" and foreign policy tool.

Consequently, there has been some discussion as to how to "Africanise" democracy. Mr Zimba suggests incorporating traditional power structures into formal government.

"At the moment chiefs are seen as political footnotes, even though they are often more effective and revered than politicians. Politicians recognise the influence of traditional leaders on how communities vote during elections and try to manipulate this. A better system would be some kind of bicameral government, even giving traditional leaders legislative powers."

As with any healthy democracy, there is a range of opinions and robust debate, but the consensus seems to be that whilst democracy is not delivering as well as it could be for Africa, it remains the most viable form of government for the continent.

Mr Ngoma sums it up: "Democracy on paper is very beautiful, but the practice depends on what practitioners actually do - and often they're not doing very well."

- Published24 September 2013

- Published24 June 2013

- Published5 April 2013

- Published12 March 2013

- Published26 March 2012