Central African Republic crisis: Another French intervention?

- Published

France already has troops stationed in the Central African Republic to protect its own interests

A fresh crisis in Africa - and once again French troops are on their way. This time around 1,000 extra soldiers are heading to the Central African Republic (CAR) to restore order after a rebel takeover. They will supplement the 400 odd French troops already on the ground in the country.

So what's new? Is this just a case of Paris once again acting as gendarme in a former sub-Saharan colony?

Are we back to the days when the famously influential Jacques Foccart acted as Africa adviser in the Elysee Palace and French paratroops made and unmade governments, protecting allies - some of them deeply unsavoury - and displacing supposed troublemakers?

It's tempting to drag out all the old cliches. After all, the CAR is the remote backwater briefly transformed into a titular "empire" in the 1970s by the bizarre Jean-Bedel Bokassa, who allegedly studded his friendships in the French elite with diamonds.

When Bokassa's credibility was finally shattered by allegations of cannibalism - although this was never proven - French troops intervened. Operation Barracuda saw Bokassa overthrown and former President David Dacko installed in his place.

But the temptation to reach for old history should be resisted. We are not in the 1970s. Africa has changed. And so has France.

Opt to act

Paris has started to send extra troops to reinforce an under-powered regional intervention force led by the African Union (AU).

Militia fighters say they are protecting their village from former Seleka rebels

The peacekeepers are struggling to restore order in a huge country where warlords and criminal gangs, many of them foreign, have run amok.

The unrest is now sparking a dangerous new spiral of inter-communal religious conflict between local Christian and Muslim communities. Some 460,000 people have been driven from their homes and more than a million are dependent on external aid.

It is this catastrophic humanitarian and security crisis that France is now seeking to help contain with the despatch of the heavily equipped troops and high tech support that only a major military power can provide.

Paris has been trying to stir international engagement since September, when President Francois Hollande put the CAR at the centre of his address to the United Nations. It has drafted a Security Council resolution that this week should give UN backing for a beefed up AU or UN force.

But such operations need time to organise, and finance. And in the meantime, an emergency is worsening by the day. So after talks with Central African Prime Minister Nicolas Tiangaye, the French have opted to act anyway.

This humanitarian security intervention, acting to complement an international or African Union effort, is a far cry from the self-interested military meddling of the immediate post-colonial era.

Fundamental reform

To outside eyes this may seem a new and sudden change. But in fact the nature of French military engagement in Africa has been evolving from the old paternalism for almost 20 years.

The UN says around 460,000 in CAR people need shelter

A key turning point was the 1994 genocide in Rwanda. French troops supposedly sent to protect refugees ended up creating the space for many genocidal killers to escape across the border to Zaire, now Democratic Republic of Congo.

This episode provoked painful reflection among French policymakers, particularly Alain Juppe, who was foreign minister at the time. Becoming prime minister shortly afterwards, he launched a fundamental reform of France's Africa policy which was continued by his Socialist successor Lionel Jospin.

And after Nicolas Sarkozy became president in 2007, the process was taken a step further, with a review of France's permanent military deployments and a rewrite of longstanding bilateral defence accords with African allies, abandoning the commitment to use military force in defence of incumbent friendly regimes.

Consensus

During these almost two decades of reform, France has continued occasionally to intervene, but increasingly it has done so in a neutral peacekeeping role.

It made a vain effort to hold the ring between government troops and mutineers in the CAR in the late 1990s.

But wherever possible France has sought to operate as part of a UN or European Union force, rather than acting on its own. In 2003, France led Operation Artemis to tackle militias who were killing civilians in north-eastern DR Congo. It was the first autonomous EU military intervention outside Europe.

France's experiences in Rwanda in 1994 sparked a change in policy

In Ivory Coast in the 2000s, France's Licorne force worked alongside UN troops to maintain the line of partition between the government-controlled south and the rebel-held north.

In the CAR, French troops and regional peacekeepers collaborated in fighting to prevent a rebel takeover of communities in the north. And Mr Sarkozy subsequently persuaded EU partners to join France in deploying the Eufor force to secure the Central African and Chadian frontiers with Sudan's troubled Darfur region in 2008-09.

But not all the interventions of the Sarkozy era commanded consensus.

In Ivory Coast in early 2011, operating under the authority of the UN Secretary General, French troops helped former rebels loyal to election winner Alassane Ouattara capture Laurent Gbagbo, the defeated incumbent, who had opted to fight rather than accept the outcome of the November 2010 presidential contest.

This intervention to support the enforcement of Mr Ouattara's election victory was in line with the stance taken by the Economic Community of West African States (Ecowas) bloc, to which Ivory Coast belongs. But it discomfited Mr Gbagbo's allies such as South Africa and Angola.

More contentious still was the 2011 French and British intervention in Libya, to support rebels fighting Muammar Gaddafi. This angered many sub-Saharan leaders because the AU was trying to achieve a negotiated solution.

Partnership of respect

Mr Hollande came to power in France in May 2012, just weeks after jihadist groups had taken over northern Mali. Yet in handling this new crisis he made a point of breaking sharply with Mr Sarkozy's unilateralist tendencies.

Mr Hollande has been in close discussions with Mali's Ibrahim Boubacar Keita

Mr Hollande has argued that the relationship between France and Africa must be a partnership of respect, even when there are disagreements. And he has gone out of his way to consult African leaders before launching military action.

When jihadists launched a fresh offensive in January 2013, threatening to break through into the south of Mali, France knew that it alone had the military capability to stop them.

The African deployment planned for later in the year could not be brought forward in time.

Although the US has regularly trained West African armies for combat against jihadists, France was uniquely well-placed to stage a direct military intervention in Mali, because of its long experience of operations in Africa and its existing military presence.

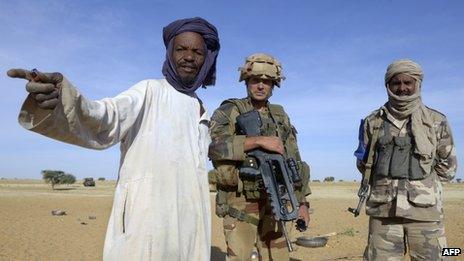

France was uniquely well placed to intervene against jihadists in Mali

Once Mr Hollande took the decision to intervene, his commanders were able to despatch special forces combat helicopters from Burkina Faso, to stage initial strikes against the jihadists. France also mobilised warplanes based in Chad, special forces based in Senegal and armoured units from its operations in Ivory Coast.

But even as final military preparations were being made, Mr Hollande and his ministers made a point of calling leaders across Africa to seek their views.

The warm sub-Saharan welcome for the Malian intervention has helped to create a climate in which France can more easily intervene in the CAR. And that subject will surely have been on the menu of Mr Hollande's talks with President Jacob Zuma during a recent visit to South Africa.

This time, as in Mali, the African political ground for a French deployment has been carefully prepared.

And later this week Paris is hosting leaders from across the continent at a summit on African peace and security.