Viewpoint: What 'Madiba magic' means to me

- Published

BBC South African journalist Farouk Chothia writes a letter to Nelson Mandela about how the anti-apartheid fighter wove his magic on the generation growing up in the 1970s and 1980s.

Dear Nelson Mandela,

As your body lies in state, let me salute you for the sterling contribution you made to the anti-apartheid struggle over more than 40 years.

You were prepared to die for the freedom of black people like me. You did not just give us the vote. You helped to restore our dignity, ending to a large extent the racial abuse we had faced all our lives. We are who we are because of you - and the other great leaders of the freedom struggle.

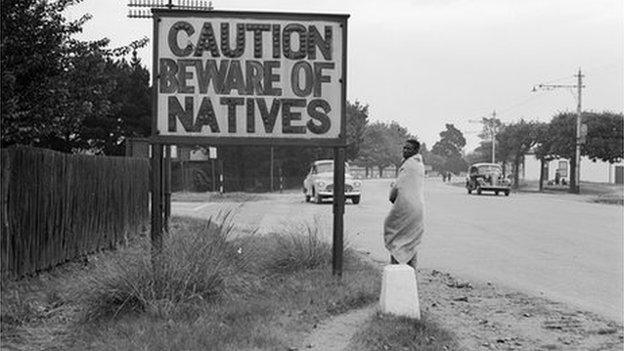

Who shall ever forget the horrors of apartheid, when many white people treated us as though we carried germs? We could not sit and stand next to them at most public places - and we certainly could not fall in love with them, the purity and supremacy of the white race had to be maintained.

We had inferior education and inferior jobs - in a nutshell, we were inferior human beings. We were told we were born stupid - that God had created us like that.

Even dogs were trained to be racist - they barked when people like me walked pass the homes of their masters. The bark got more vicious when those of a darker shade walked pass.

Apartheid-era dogs knew that there was a pecking order in apartheid - the blacker your skin the more you had to be fenced out of society. Whites were gripped by a "swart gevaar" (black threat) mentality, an Afrikaans phrase that encapsulated their fear of people of your skin colour.

Parcel bomb

I remember sirens wailing at police stations in some towns at nine o'clock every night - no "native" or "bantu" could be outside after that.

They had to be in townships reserved for them - or in their servants quarters and single-sex hostels.

The whole country has been affected by Nelson Mandela's death

All races have mourned his passing

And tens of thousands attended his memorial service at the stadium near Soweto on Tuesday

But we have come a long way - those who denounced you as racially inferior, called you a terrorist and wanted you hanged are now celebrating your life and mourning your death. They will miss you, just as I will miss you.

You are now joining the illustrious sons and daughters of the anti-apartheid struggle - the likes of Andrew Zondo, who went to the gallows singing for freedom; Ruth First, who was killed by a parcel bomb, and Ahmed Timol, who was thrown out of the 10th floor of what was then John Vorster Square police headquarters.

"Indians can't fly," some of the security policemen were said to have joked.

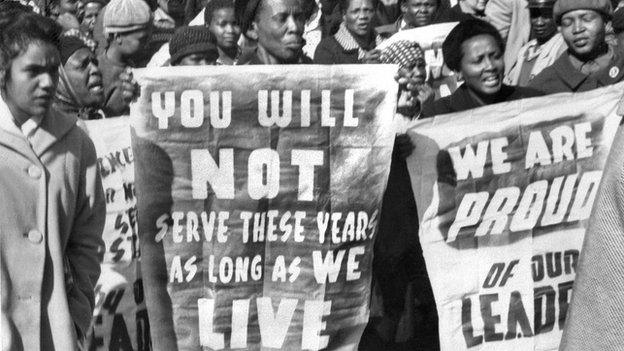

These activists all inspired me to campaign for freedom, but you, as leader of the prisoners on Robben Island, were the greatest inspiration.

I grew up with images of you as a revolutionary in the mould of Che Guevara, hearing tales of how you launched Umkhonto we Sizwe as the "Spear of the Nation"; how you slipped out of South Africa under a false name to receive military training; how you surreptitiously walked into telephone booths to call journalists as part of a propaganda war against the apartheid regime and how you disguised yourself as a chauffeur of white comrades - until you were caught in August 1962 near the small town of Howick.

Airbrushed

While you were on the run, newspaper headline writers dubbed you the "Black Pimpernel" - and it became part of the tales about you.

Nelson Mandela and his colleagues in 1964 faced the death sentence

As a child, I never really knew what it meant, but it created an aura of mystery and romance around you.

And I heard of your defiance from the dock after the prosecutor, Percy Yutah, called for the death sentence to be imposed on you.

"I cherish the ideal of a democratic and free society… If it needs be it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die."

I have no doubt that these words came from the heart, not the lips of a spin-doctor, though you did seek advice from your friend, the British journalist Anthony Sampson, on what you should incorporate in your speech for a UK audience.

Through that rousing speech you cast a spell over us with "Madiba magic", to use a phrase journalists would coin much later.

I, like millions of others, vowed to campaign until you were freed from jail. Your freedom and our freedom were indivisible.

Today, you are hailed as a champion of national reconciliation, who forgave his captors after 27 years in jail.

But I am sure you will agree with me that, on this point, you merely personified the black people of South Africa.

Have we taken revenge against those who oppressed us or tortured and killed our friends and relatives?

No. We have remained true, at least in this respect, to the lofty ideals of the liberation struggle. We still remember that it was a fight for freedom - not a fight against white people.

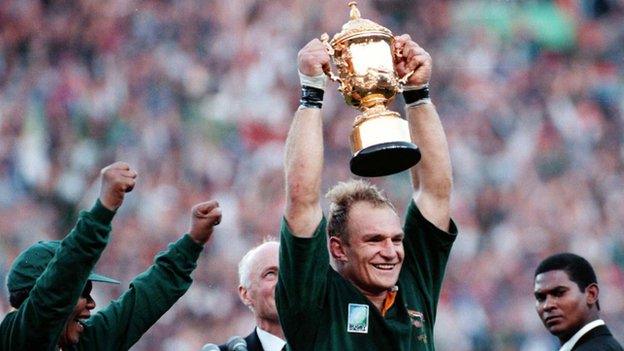

During the 1995 rugby World Cup, Nelson Mandela famously donned the jersey of the Springboks, the team beloved by Afrikaners and loathed by many black people during apartheid

Today, it is fashionable to say the Rainbow Nation emerged on 27 April 1994, when we voted in South Africa's first democratic election.

But it has existed for as long as I can remember. In fact, it was represented at your trial - weren't Ahmed Kathrada and Dennis Goldberg among your co-accused? And didn't your defence counsel include Bram Fischer, an Afrikaner, and George Bizos, who is of Greek descent?

Way back in 1956, you, along with democrats of all other race groups, drafted the Freedom Charter, which became the political loadstar of our struggle.

"South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white," it said.

Sadly, it took most of our white compatriots several more decades to grasp that we were a rainbow nation.

For them, the iconic moment came in 1995 when you wore the Springbok jersey, then a symbol of white supremacy, to celebrate their victory over the All Blacks in the rugby World Cup.

But I have never been sure about the "Madiba magic" you displayed on that day.

From then onwards, many white people embraced you as leader, but airbrushed history.

Chamberlain

They chose to ignore what happened after the World Cup when then-rugby chief Louis Luyt dragged you to court in an attempt to block you from appointing a commission of inquiry into racism in rugby.

Many white people preferred to just see you as Madiba, the president who could sing, dance and celebrate the rainbow nation's achievements.

But the factory workers, farm labourers and shack-dwellers of South Africa continue to be defined by their black race.

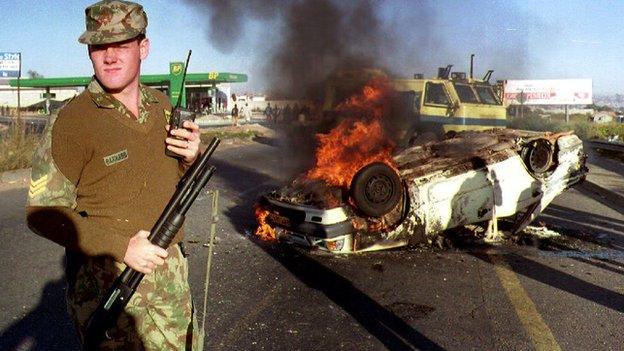

After Mr Mandela's release in 1990, the country was engulfed in flames for several years

As Jacob Zuma, the fourth president of our 19-year democracy, noted last year, there are still instances where the master reserves the front seat for his dog, while the worker is relegated to the back of his van or truck.

But thankfully, such cases are far fewer now then before your release: white South Africans, along with like-minded people from other race groups, are changing - and have turned their backs on apartheid for good.

You were right to discard your image as a revolutionary after your release from prison in 1990 and to pursue non-violent change, even when the regime's death squads were killing black commuters on trains nearly every morning.

If I recall correctly, more people were killed in the first four years after your release than in the preceding four years, as your opponents tried to destroy your support-base and mystical status ahead of South Africa's first democratic election. You did not look like a magician at the time. You appeared, at times, to be weak.

As the country was engulfed in violence - including the assassination of Chris Hani, the most popular anti-apartheid leader after you - I and many others doubted whether you were right to abandon the armed struggle.

Did you not risk becoming, as one of your more militant comrades, Harry Gwala, put it at the time, a Neville Chamberlain, the UK prime minister accused of following a policy of "appeasement" towards Hitler?

Well, you avoided that fate - and led us into a peaceful and democratic South Africa.

That, I hope, will be your lasting memorial. But I will remember you most for your role in freeing us from the chains of apartheid.

Rest in peace, Nelson Mandela.

Nelson Mandela spent 18 years in this prison cell, hidden from the world

After his release from prison, Nelson Mandela urged his supporters to support his reconciliation agenda