Nelson Mandela death: What now for South Africa?

- Published

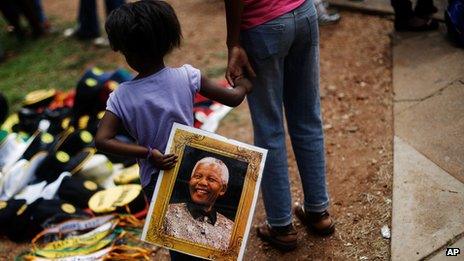

Thousands of people lined the streets to see Nelson Mandela's funeral cortege

It has been a momentous week in South Africa - of mourning, celebration, chaos, patience, booing and reflection.

But what happens now? What impact will the drama of these past few days, and the death of Nelson Mandela, have on a country that has already had plenty of practice trying to get along without him?

"It's too early to judge if there will be any fundamental change," Mr Mandela's lawyer, George Bizos, told me, with his customary good sense.

"Maybe it will awaken what he stood for in people, and they will genuinely try to mimic what he did. A galvanising moment… I hope. I think it will get home to at least some that talk is cheap. Action is needed," said Mr Bizos.

At this point, a brief word on the organisation of this week's events: no, it wasn't perfect.

There were frequent, tiresome administrative foul-ups.

There was the dodgy sign language interpreter, and Tuesday's memorial service - with its endless, mostly unremarkable speeches - was a missed opportunity to tell Madiba's story with insight and affection.

And yet this country came together, in large events and small, with dignity, passion, good humour and some impressive logistical work. I suspect most South Africans will look back on the week with pride.

Then, of course, there was the booing.

The global humiliation of President Jacob Zuma at Tuesday's stadium event was a defining "emperor's new clothes" moment - when modern South Africa's simmering frustrations briefly, but emphatically, broke the spell of Mandela "magic".

"It was humiliating," Mr Zuma's foreign affairs adviser Lindiwe Zulu conceded to me the following day.

But she insisted the governing ANC - which retains, let's not forget, an overwhelming electoral mandate - would continue to "carry on (Mandela's) legacy".

"We have been trying by all means to make sure that we don't do things that would upset him."

But a growing number of South Africans appear to disagree.

'No catastrophe'

"It was a wake-up call for the politicians," said Moeletsi Mbeki, a businessman and long-standing critic of the ANC.

"It doesn't mean they'll do anything about it, but at least they know how seriously people take their incompetence and corruption. People have lost all respect for Zuma and his government. They are a very, very motley crew.

The focus wasn't entirely on Mr Mandela at Tuesday's service

"The ANC made a huge mistake in trying to think it could present the current leadership as a continuation of the Mandela generation. It's not."

But if Mr Mbeki sees "the writing on the wall" for the ANC, he is more optimistic about the country.

"We have very high moments and very low moments. We never seem to be somewhere in between… but I don't think any catastrophe is waiting for South Africa. We have strong institutions."

Dr Mamphele Ramphele, former partner of the murdered Black Consciousness leader Steve Biko, was also in the stadium in Tuesday.

She told me she believes the ANC hijacked what should have been a non-political event, and that the booing was a reaction to "the rot, the betrayal of Mandela's style of leadership... and the intimidation within the ANC".

"It is a turning point, in that once the genie is out of the bottle in terms of dissent… it's going to be difficult for discipline to be returned."

Dr Ramphele has a political axe to grind. She recently formed her own party, Agang, which hopes to challenge the ANC at next year's elections.

Not surprisingly, perhaps, she sees "an opportunity" in political terms, in the death of Nelson Mandela.

"Many people will feel freer to express themselves in terms of their disapproval of the ANC's performance.

The attention now is on South Africa's future

"If people want to honour Mandela they've got to be loyal and honour his values, not an organisation that is undermining those values. His passing may open the way for those people who have been reticent," she said.

Whether this transpires remains to be seen. Measuring the precise impact of Mr Mandela's death will, as George Bizos pointed out, be hard to pin down.

For a young democracy like this, perhaps the most important thing about this week - and about Madiba's legacy - is that his passing will not, and should not, have any great, disruptive influence.

We can briskly nudge aside the paranoia, conspiracy theories, and quiet racism, which have always hovered on the edges of this topic.

No, Mr Mandela was not some mystical, moral corset, keeping South Africa's leaders in line even from his hospital bed.

And no, his death has not triggered a bloodbath of any sort - nor will it.

But there is a broader point. Emerging from all those years in prison, Mr Mandela relentlessly preached tolerance, and the primacy of negotiations.

South Africa, it seems, has not forgotten that.