Will Binyavanga Wainaina change attitudes to gay Africans?

- Published

With internationally acclaimed Kenyan author Binyavanga Wainaina coming out, Africa's embattled gay rights movement finally has a public face around which to rally support for equality, writes BBC Africa's Farouk Chothia.

"What he has done is brilliant. He is admired and respected, and the only high-profile [black] African to come out," Nairobi-based gay rights activist Anthony Oluoch told the BBC.

"He gives a different face to gay people, breaking the stereotype that they are effeminate, that they don't have jobs, that they are completely different."

Mr Wainaina's decision to reveal his sexuality, in a short essay entitled "I am a homosexual, Mum", external, comes amid growing hostility towards gay people in several African states, despite threats by the UK and other Western powers to cut aid if anti-gay laws are not scrapped.

"Western governments must learn to use soft power. Otherwise, they end up doing more harm," says UK-based Justice for Gay Africans campaign group co-ordinator Godwyns Onwuchekwa.

"You can't tell African people you won't give them aid unless they do what you want them to do. They will tell you to go to hell. They have their pride."

Nigeria is a microcosm of the continent with a large population of both devout Muslims and Christians. It is currently leading the campaign against gay people, tightening laws, carrying out arrests and allowing Islamic courts to punish homosexuals.

'Hateful yarn'

For Mr Onwuchekwa, a Nigerian, this comes as no surprise, as opposition to gay rights is one of the few issues around which Nigerians, who are deeply split along religious lines, unite.

"Politicians in Nigeria have to prove they are religious. If they want votes, they've got to go to church or mosque. That gives pastors [and imams] influence over their campaigns," Mr Onwuchekwa told the BBC.

Most Africans believe that homosexuality is un-Christian and un-Islamic

Nigerian cleric Peter Akinola (R) led the campaign against gay rights in the Anglican communion

Defending the new legislation which bans same-sex marriages, gay groups and shows of same-sex public affection, Mr Jonathan's spokesman Reuben Abati said: "This is a law that is in line with the people's cultural and religious inclination. So it is a law that is a reflection of the beliefs and orientation of Nigerian people."

South Africa-based gay rights activist Melanie Nathan argues that the US Christian evangelical movement is also shaping public debate, playing a key role in Uganda's parliament passing a new anti-gay bill in December, which makes it a crime not to report homosexuals to police and to talk about homosexuality without denouncing it.

"When religious extremists... found that their war against homosexuality was floundering on home turf, they scrambled to capture a world ripe for scapegoating, using the Bible to spin their hateful yarn on African soil. Uganda became a target and they were successful," she blogged, external.

"Their target included, not only the general Ugandan populace, but also the Ugandan politicians and Members of Parliament, who subscribed to their interpretations, that Gays are not fit to live 'because the Bible says so!' This trend has spread across the continent. And anti-gay laws have been passed, compliments U.S. Evangelicals."

Several prominent US evangelical preachers have denied any links to the Ugandan bill.

In any case, Mr Onwuchekwa says there is genuine opposition to gay rights within African churches.

'Unnatural'

"If you look at the worldwide Anglican communion, the former head of the church in Nigeria, Peter Akinola, was at the forefront of the campaign against gay people. Churches in Africa may be getting support from the West, but so do LGBT [lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender] groups. It's part of the game," he told the BBC.

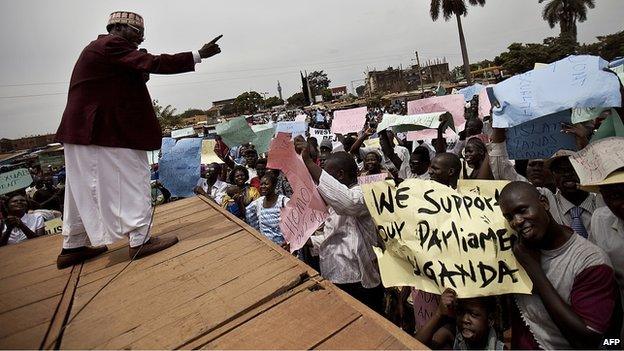

Ugandan clerics have been vocal in their support for harsher penalties

The gay rights movement grew after the advent of multi-party democracy

Malawi's President Joyce Banda tried to buck the trend in 2012, promising to repeal laws which banned homosexual acts.

But she dropped the idea after a backlash from the Malawi Council of Churches, a group of 24 influential Protestant churches.

"Our stance has always been that this practice should be criminalised because it runs contrary to our Christian values," said the secretary-general of the Malawi Council of Churches, Reverend Osborne Joda-Mbewe.

But rights groups have not given up, launching court action to declare Malawi's anti-gay laws unconstitutional and to secure the release of three men - Amon Champyuni, Mathews Bello and Mussa Chiwisi - imprisoned in 2011 for engaging in "unnatural acts".

'Enemies of faith'

"As long as same-sex relationships are consensual and done in private, no-one has business to get bothered," said Gift Trapence, the executive director of the Centre for Development of People, one of the groups fighting the case in court.

In a report published last year, external on attitudes towards gay people worldwide, the US-based Pew Research Center said hostility was strongest in "poorer countries with high levels of religiosity", while there was "greater acceptance in more secular and affluent countries".

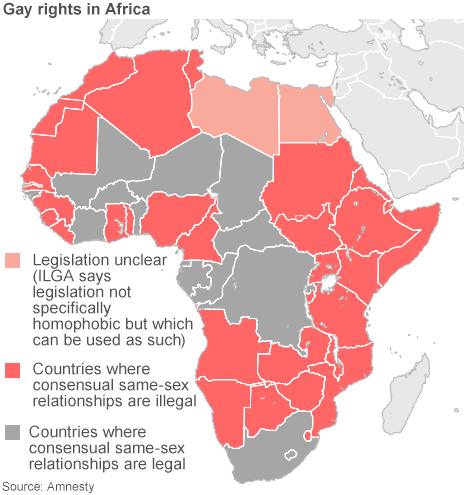

"Publics in Africa and in predominantly Muslim countries remain among the least accepting of homosexuality," it said, pointing out that its survey showed that 98% of Nigerians, 96% of Senegalese, Ghanaians and Ugandans and 90% of Kenyans were opposed to homosexuality.

"Even in South Africa where, unlike in many other African countries, homosexual acts are legal and discrimination based on sexual orientation is unconstitutional, 61% say homosexuality should not be accepted by society, while just 32% say it should be accepted," the report said.

This is despite the fact that South Africa's leading Christian clerics - including Archbishop Desmond Tutu - are vocal supporters of gay rights.

"Anywhere where the humanity of people is undermined, anywhere where people are left in the dust, there we will find our cause," he said last year.

Religious leaders have the power to sway votes in elections

But the liberal voice of South African clerics is drowned out by those elsewhere on the continent.

Rejecting calls in 2012 for Kenya to legalise homosexuality, a local Anglican bishop, Julius Kalu, said "liberal teachings" about gay rights posed a bigger threat than some of the violence unleashed by militant Islamists.

"The Church is at war with enemies of the faith," he said.

"Our greatest fear as a church should not be the grenade attacks, but the new teachings like same-sex marriages."

Mr Oluoch says the gay rights movement emerged in Africa following the collapse of repressive one-party rule in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

'A journey'

"People began to realize that they have rights that are being denied to them just because of who they are and who they love. That gave rise to the gay rights groups," he says.

However, no democratic government - except South Africa's - has repealed anti-gay laws. In fact, the opposite is happening, with politicians and religious leaders whipping up hostility against homosexuals.

South Africa is the only African country which recognises same-sex marriages

For Mr Oluoch, this is not surprising as the growing profile of gay groups is a "double-edged sword".

"Once people are confronted by something they don't understand, the first instinct is fear and an obvious backlash," he says.

"But with visibility comes understanding and the eradication of ignorance. Today I can go on TV and say I am gay and educate people about gay rights. I couldn't have done that in the past. The tide will eventually change for the better."

The 43-year-old Mr Wainaina, who says he knew he was gay since the age of five, told the BBC that most people have reacted positively to his decision to come out and he would champion the rights of gay people in Africa.

"It's probably the most popular thing I've ever written - and it is not fiction it is the truth," he told the BBC's Focus on Africa programme.

"I come with love to this conversation... I'm interested in taking on the foaming dogma group," Mr Wainaina said.

Mr Oluoch, a 26-year-old activist who works for the Kaleidoscope Trust rights group in Kenya, says he came out three years ago.

"I had to since I would appear in the media talking about LGBT issues and thought it was the right time to come out. Some people changed their attitudes towards me but ultimately, the people who mattered are still in my life," he told the BBC.

He says he hopes Mr Wainaina's decision will spur other high-profile Africans to come out.

"But as I always say, coming out is a personal journey that one has to take and find a time that works best for them. There should be no pressure. In Binyavanga's case, it took more than 40 years."

- Published18 May 2013

- Published17 January 2014

- Published16 January 2014

- Published2 January 2013

- Published16 June 2010