CAR: Obituary for a village mayor

- Published

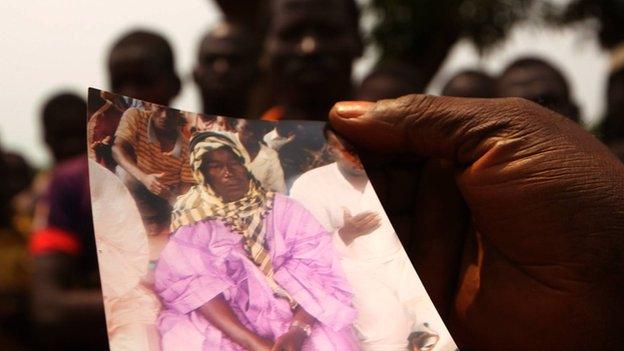

Dewa Adamou's brother was grief-stricken at the killing

You will struggle to find Dewa Adamou's village on a map.

Take the road south-west out of the capital, Bangui, and keep driving until the tarmac runs out and the forest - giant pylon-like grey trees with broad green canopies - closes in on a lumpy dirt track.

After a couple more hours, and a dozen, occasionally menacing, roadblocks, you may notice a few mud-brick buildings on your left and then a small, white-painted mosque on the right.

This is Boboua. Most of the village is invisible from the road. But it is home to approximately 6,500 people, who farm coffee and a few other crops in the overgrown fields nearby. There are teak plantations further up the road, a row of beautiful hills to the east, and diamond mines further west towards Cameroon.

Mr Adamou, 58, a Muslim and a coffee farmer, has been Boboua's mayor since 1997. Those 17 years imply a certain measure of success and popularity.

Not that he has brought much wealth to the village. The dirt road, interrupted by a few precarious wooden bridges, gets worse with every rainy season, and there is still no electricity, no fresh water, and no mobile phone signal in Boboua.

Mr Adamou's house is beside the road at the south end of the village. His brother, Yussuf Nana, lives next door with his family and four wives, beside their coffee mill, in a compound walled off by corrugated iron sheets.

Roughly 1,000 people in Boboua are Muslim. Mr Adamou's father came from Cameroon originally, in the days when borders meant very little. His descendants now consider themselves patriotic citizens of the Central African Republic. Mr Adamou was mayor of the whole village - not just the Muslims.

Grainy family photographs show him seated on the floor in flowing robes with a broad, generous smile.

Anyone driving to Boboua today will notice a consistent pattern. In every single village on the route, the local mosque and often several buildings around it have been recently destroyed. Some have been burned. The rubble is often smoothed over, as if the community were trying to erase all evidence that the buildings ever existed.

But not in Boboua. The mosque, and indeed the entire village, appears to be intact.

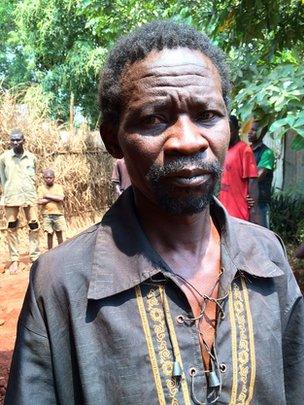

Mayor Adamou had earned the respect of Christians and Muslims alike

Last year, CAR was overrun by the Seleka rebels - a brutal alliance of northern groups and foreign fighters from Chad and Darfur. The overwhelmingly Muslim force terrorised huge swathes of the countryside, forcing tens of thousands of families to flee into the bush for months at a time.

But not in Boboua.

Tears roll down

"The mayor talked to the Seleka. They left us alone. He was a good man," said Landry Mandamoko, a 23-year-old Christian man at the roadblock on the northern edge of the village.

Blood stains still visible at the spot where the mayor was killed

Last month, the mayor's restraining influence was again called for following the withdrawal of the Seleka, and the resignation of their President Michel Djotodia.

In hundreds of towns and villages, angry crowds turned on members of the Muslim minority, accusing them of siding with the Seleka. The crowds attacked their mosques and homes. Many people were killed.

But again, not in Boboua.

"We must live together. We have always lived together," said Yndoko Eremo, the village's Catholic priest.

I met the Father Eremo and the mayor's brother Mr Nana, on Friday morning. They were standing together at the edge of the village with a handful of others, looking agitated and scared.

Mr Nana led us to his compound, showed us two freshly dug graves, and threw himself onto the soil, wailing with grief. Tears rolled down the priest's cheeks as he watched the scene.

It appears that a group of about 20 outsiders - members of the anti-balaka militia that sprung up across the countryside last year to protect communities from the Muslim Seleka fighters - had come to Boboua the night before.

It was about 03:00. They went straight to the mayor's house, took him outside and tied his arms behind his back. They did the same to one of his teenage sons, Abubakar, and to another young man called Abdul.

The anti-balaka then took their three prisoners across the road to the mosque, pushed them to the ground, and killed them with a shotgun and machetes. Blood stains are still visible on the dirt outside the mosque door.

Everyone in the village reacted to the night-time killings by running into the bush to hide. Only a few dozen people had dared to return by the time we reached Boboua a day later.

Almost inevitably the incident has broken the village's precarious sense of unity and tolerance. Presumably that was the killers' intention.

The mayor's brother said he suspected the anti-balaka militia had been working with a local Christian councillor. "He's a murderer, a traitor," said Mr Nana, shaking his fist. Others insisted that was not the case.

Anti-balaka fighters want to chase all Muslims out of the Central African Republic

Some villagers told us the killers had left along the road to the north-west. We drove that way and, perhaps 20km outside Boboua, we ran into a group of anti-balaka.

Too few peacekeepers

There were about a dozen fighters. The youngest was 15 years old. They brandished the usual assortment of machetes, homemade rifles and knives, and wore amulets around their necks and various brightly coloured hats.

In recent weeks the anti-balaka have spiralled out of control - a low-key civil defence movement transforming into an anarchic gang of thugs, preying on civilians and openly boasting of their near-genocidal attitude towards Muslims.

It soon became clear, from their erratic behaviour, that the group we had run into were high on drugs. One of them began muttering about some dead bodies that he wanted to show us, but the others quickly told him to shut up. I asked them about the killing of Mayor Adamou.

"It's good he's dead," said a man who called himself Banda Crisostom. "He was a Muslim and we must kill all Muslims. Every one of them."

I asked if his group was responsible and he denied it, but said another group, led by a man called "Firme" had passed through their roadblock a day earlier and boasted of the killing, showing them pictures or video of the attack filmed on a mobile phone. The group, he said, had gone ahead to the nearby town of Boda.

In Boda, a contingent of French troops was trying to keep the peace, stationed on a small hill in the centre of town between the heavily looted Christian and Muslim neighbourhoods.

Father Eremo fears for the future of Boboua

A French captain told me the situation in town had stabilised, but that the fighting would no doubt resume the moment his forces left.

I told him about the situation in Boboua. The villagers there had begged me to ask the French or other African peacekeepers to send troops to protect them. "We are aware of the situation. But my zone of responsibility only extends to the town and the immediate area around it," said the Frenchman.

At Boda's cathedral, anti-balaka fighters were mingling with several thousand civilians. I asked if anyone knew of a man called "Firme" or of any fighters who had taken part in the attack on Boboua. Not surprisingly, I was told that the attack was the work of another group, which had gone off in another direction. Nobody could offer more information.

"There will be no peace in town until all the Muslims have left," said one fighter.

As we were leaving Boda, we spotted a French patrol accompanying a small group of perhaps 20 Muslims to the local airstrip to catch a private flight to Bangui.

There are clearly nowhere near enough foreign troops in this country to protect Muslims in every town or village. And so the French and other African peacekeepers often seem to find themselves in the awkward - some would say shameful - position of facilitating the Muslim community's departure.

Earlier, in Boboua, I'd asked the mayor's brother if he planned to join the tens of thousands of Muslims now trying to flee from the Central African Republic.

"Where would I go?" he asked. "This is our home. We belong here."

It is hard to say what will happen to Boboua in the days or months ahead. It is tempting to conclude that mayor Adamou's message of tolerance will be brushed aside by the larger forces of anger and revenge now sweeping through the country.

But for now, those few families who remain in the village are trying to cling on to what is left of his legacy.

The mayor's brother finished weeping on the grave and stood up. Father Eremo pointed at the pile of earth, and at another, bigger grave beside it where the other two bodies were buried together.

"It was me. I dug the graves yesterday while the others were hiding in the bush. It was the right thing to do," he said.