How South Africa is learning to live with mixed-race couples

- Published

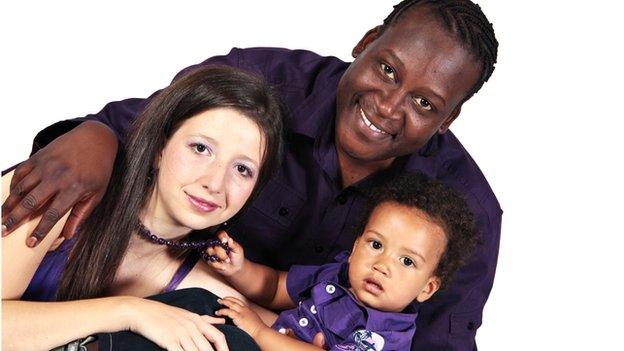

Mpho Lakaje, his wife Daniela and son Mpho jnr

Under apartheid inter-racial relationships were banned in South Africa. Journalist Mpho Lakaje, who is married to a white woman, reflects on how the country has changed in the 20 years since the end of white minority rule.

When I started dating the woman I was to marry many of my friends and some of her family - black and white - were united in opposition.

Some members of Daniela's family were not at all keen. One even refused to let me into their home.

They told her that I was "not good enough for her".

My peers from Soweto were equally opposed.

One of my childhood friends, Muzi, repeatedly told me he would never date someone who was not Zulu, let alone a person who was not black.

So when he first saw my white girlfriend, the reality of living in a non-racial country finally hit him.

The Mandela effect

Thankfully, most of my family members, including my grandparents who experienced the brutality of apartheid and racism first hand, surprised me by warmly welcoming my wife-to-be.

I was born in Soweto, the famous Johannesburg township that used to be home to Nelson Mandela.

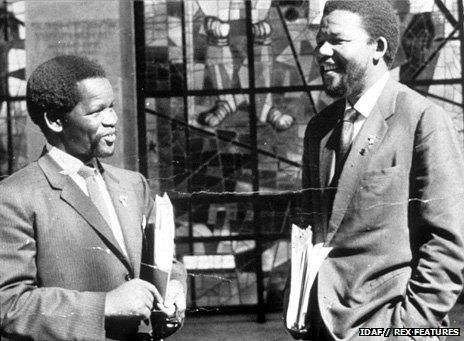

I come from a family of freedom fighters and learned about prominent anti-apartheid leaders like Oliver Tambo, Solomon Mahlangu and Anton Lembede at an early age.

My whole life I was indoctrinated and made to believe that I would grow up, go into exile in Southern Africa and come back to my country to fight white people.

When I first saw an AK47 in my uncle's room, my political beliefs intensified.

The same month that Mr Mandela left prison in February 1990, I celebrated my 10th birthday.

I remember vividly how some in my community thought that this was the moment for exiled freedom fighters to return home and drive white people out of South Africa.

Mpho's family was steeped in the fight against apartheid led by figures such as Nelson Mandela (R) and Oliver Tambo

But the tone in my family gradually changed as we approached South Africa's first democratic elections in 1994.

Elders at home began to help the young ones understand the concept of forgiveness and reconciliation as advocated by Mr Mandela. These were profound lessons that gradually and drastically changed my views too.

When I went to college to study journalism, I was exposed to students from different parts of the world.

I was now living in a cosmopolitan environment.

As a young man in my 20s, I was in experimental relationships with girls who were not from my background. In later years, it did not matter to me whether a person was a white South African, Portuguese or Angolan.

However, many of my black friends couldn't understand the logic behind hanging out with people whose languages we did not understand. Personally, I was fascinated by learning about a world different to mine.

As a result, I had a burning desire to travel.

Fortunately for me, many of my dreams came true. I became a journalist and joined the BBC World Service, getting an opportunity to see the globe.

Changing attitudes

In 2007 I met Daniela Casetti-Bowen, who had come from Chile to study tourism in South Africa. We became friends and later started dating. Two years later, against her family's will, we moved in together.

Mpho and his wife say their experience is better than many

Daniela's uncle, who arrived in South Africa in the early 1980s, was extremely sceptical about our relationship. He refused to let me inside their house. Daniela's white South African friends also warned her about dating a black boy from Soweto.

Daniela and I had to take a conscious decision to disregard those opposed to our relationship.

Most of my relatives told me it did not matter to them whether my partner was black or white, South African or not.

While I was a bit shocked by their open-mindedness, I also saw their actions as a demonstration of their authentic commitment to Mr Mandela's dream of a Rainbow Nation.

But post-honeymoon, reality hit and we started experiencing challenges that come with inter-racial relationships. Some of Daniela's relatives discouraged us from starting a family.

They said mixed-race children always had a tough upbringing because they do not have an identity.

Again, we ignored this advice and went on to have a baby, Mpho Jr.

Interestingly, relations between myself and Daniela's family have improved tremendously in recent years.

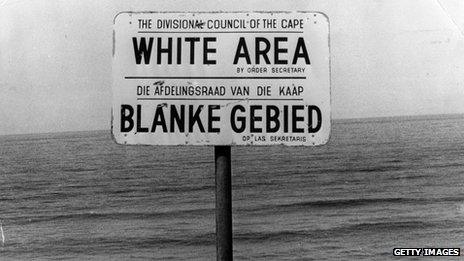

Where once black and whites would never have mixed, occasions such as sporting events bring South Africans together

However, problems started to arise from my side of the family. Questions were being raised about Daniela's "lack of commitment" to our traditions.

Daniela and I both agreed that culture evolves and therefore we would only follow what is practical.

But some members of my family remain totally opposed to our views. They feel that Daniela needs to follow or perform most of our traditions.

For example, shortly after our son was born, Daniela was supposed to spend 10 days at my mother's house with the baby. But for us, this was not practical.

However, there are many things that Daniela has agreed to do. For example, my family insisted on shaving our son's head at three months as opposed to my wife's belief that this should be done immediately after birth.

But my feeling is that Daniela and I have it easy compared to some of our friends in mixed-race relationships.

Bevin van Rooyen is a coloured (mixed-race) man who was born in Johannesburg. He met his girlfriend Jacqueline Louw, a white South African, while studying at an arts college in Johannesburg.

Born in 1984, Bevin, like me, did not experience much racism while growing up because South Africa was beginning to change.

"I only started experiencing racism when I met Jacqueline's family," Bevin tells me. "I was completely shocked. I did not know what was happening."

While Bevin's parents welcomed his partner into their family, Jacqueline's did not.

"From the beginning, it was a problem with me not being white. I was not welcome in the house. Her dad had issues," Bevin tells me.

When they started dating, the pair kept their relationship a secret from her family.

"When they found out, they kicked her out of the house and she had to move in with me and my folks," Bevin remembers.

'Engraved racial classification'

Another friend, Jake Scott, arrived in South Africa in 2009 and is now a citizen. He was born and raised in West Virginia in the United States. His mother is white and his father is an African-American.

Sign posts indicating whites only areas were common during the apartheid era

Jake's wife Mandi is a black woman from Soweto. Most days, Jake is in the shanty town of Diepsloot where he runs an organisation that introduces young people to theatre, sports and music.

"At times somebody would refer me as a white person. There are times I would say: 'Wait a second, I'm black'," Jake says.

He says they get "the looks" when walking through the shopping centre with his wife but he is not too worried about it.

"This racial classification is very engraved," he says. "It's like in the psyche of South Africans."

As South Africans we still have a long way to go before we can fully embrace each other. I consider myself fortunate to be educated and liberal.

But the reality is, I have many friends, black and white, who are not ready to live in a non-racial society. I remain optimistic though.

My country is definitely not where it was 20 years ago. We have made progress.