Marikana: Hunger, fear and defiance

- Published

- comments

Which will win: Hunger, fear or defiance?

On the dusty plains north of Johannesburg, a gruelling battle is taking place in the world's biggest platinum mining community, as the longest, most destructive strike in South African history enters its fifth month.

"We just want it to end. We go to school hungry. It's hard to concentrate," said 18-year-old Thabiso, surrounded by five friends, who all nodded vigorously in agreement as they walked home from school past the grey buildings of the now-silent Marikana mine - notorious as the place where police shot dead 34 striking miners in 2012.

The children's mothers had been standing on the roadside nearby since before dawn, having heard that a local charity might be handing out food parcels.

"There is no money. We are struggling. But we are angry - we want 12,500," said Wendy, who did not want to give her surname.

That is 12,500 South African rand - approximately $1,200 (£700) - and is the totemic figure claimed as a non-negotiable entry-level wage demand by the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (Amcu), the fiery new union that has swept to prominence on the platinum belt in recent years.

The three mine owners at the centre of the strike - Lonmin, Amplats and Impala - say that figure, almost triple the current basic wage, is simply unaffordable. Union and management are currently locked in a new round of negotiations.

Poverty and unemployment are rife in the informal settlement a few metres from Lonmin's Marikana mine

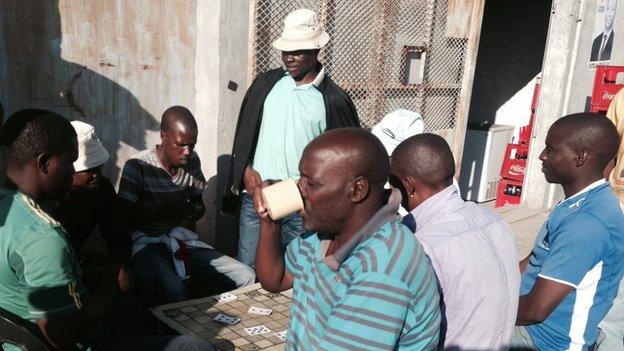

"All of us, we're prepared to die, if we don't get that 12,500," declared Kaiser Madiba, sitting playing a card game called "casino" with a group of striking miners in the informal shanty town of corrugated iron shacks, close to the spot where their 34 colleagues were shot dead almost two years ago.

Lonmin says the strike has already cost it a third of annual production, but Mr Madiba shrugged off the threat of bankruptcy.

"That is not our problem. Another company will come," he insisted.

But not every miner shares that defiance.

As the strike drags on and pressures on families intensify, a growing number have indicated a desire to return to work, but complain that they are being prevented by intimidation, and even by murder.

'Army intervention'

"They stop us from going to work. I've been attacked three times, my wife got a miscarriage and our house was burned down," said Fred Mekgwe, a worker at the nearby Impala mine and a member of the once dominant National Union of Mineworkers.

"I want that money. I'm not against the strike, but they're disrespecting the picketing rules," he said.

"This is a democracy, but it's not working for us. People are being killed."

Many strikers spend their days drinking at the taverns that line the dusty streets of Marikana

Mr Mekgwe had agreed to meet in a neutral spot, far from his home village.

As he left, another miner approached me, saying he too was scared for his life.

"I'd like to go back to work," said Thabiso Arelesego.

"I don't have any food left at home. Let's say out of 10, about eight of us want to go back to work - the ratio is very high.

"Maybe if the army would intervene we'd be safe, if the army moved around the villages and the shafts."

The immediate priority may be to broker an end to the current strike, but there is a growing acknowledgement that more substantial reforms are needed to save the industry.

The proposals include a radical change to shift patterns, better housing for migrant workers, empowerment deals to give employees a real stake in their companies, a return to the disciplines of collective bargaining, and a frank assessment of executive pay levels.

"The industry needs to change the way it's been structured," said Gavin Hartford, an industrial sociologist and mining consultant.

"We're one of the most unequal societies in the world and I don't believe we can deal with the labour problems if we don't grasp that nettle."

Following a cabinet reshuffle, there is a new mining minister in place, but suspicion of the state - the police and the governing alliance which includes the trade union federation - runs deep in places like Marikana, and strong leadership appears to be in short supply.

"There's a long road and a long journey of change still to happen, and it requires significant leadership… to create a productive, humane mining industry," said Mr Hartford.

"The sine qua non… requires us to be very honest about our failures."

In the meantime, the local economy around Rustenberg - as well as the Eastern Cape where many of the migrant workers come from - is reeling under the devastating impact of the strike.

"This is not taking us anywhere. The economy is going down. It's not only the mining industry," said Mr Mekgwe.

" The salary I'm getting is not enough, but it is my responsibility and the responsibility of the company to resolve this in an amicable way."

- Published16 August 2013

- Published15 August 2013

- Published19 September 2012