Kenya's wrestle with insecurity

- Published

It was a reasonably thorough body search. "How did I do?" said the Kenyan security guard afterwards, fishing, unexpectedly, for a compliment.

"Was it properly done? If so, please tell your country it is safe to come here…"

We were at Kenya's Mombasa airport - the sun shining earnestly outside; gentle waves tripping over the nearby reef; cocktails and deckchairs beckoning lazily from the white beaches of the Indian Ocean.

But the beckoning does not seem to be working so well these days.

The foreign tourists are staying away.

Some hotels have closed down altogether.

Others have that awkward, apologetic feeling - of too many waiters hovering round the one busy table; the souvenir sellers squatting in the shade outside, spotting our TV camera and worrying that we are going to scare away what is left of their business.

"It is never been this bad," said Sultan.

"Are you sure you don't want a carved elephant?"

Kenya is a spectacularly beautiful, dynamic democracy.

Chefs along the coast are laying on the food for very few guests since travel warnings were issued in May

The Chinese are busy building a brand new train line from the capital, Nairobi, to Mombasa's busy port.

There is plenty to be optimistic about here.

But the country is also wrestling with some huge - and increasingly pressing - challenges: Deep ethnic divisions, an enduring culture of impunity, corruption, and the growing threat posed by home-grown militants, and by Islamist fighters from neighbouring Somalia.

I used to live in Kenya a decade ago - and remember the indignant rage of local tour operators each time the UK or the US issued a new travel warning, and the holiday industry slumped a little further.

Well now it has slumped by about a third - in a few short months.

The sort of blow that few businesses can endure for long - and not something Kenya can afford either.

Speech backfires

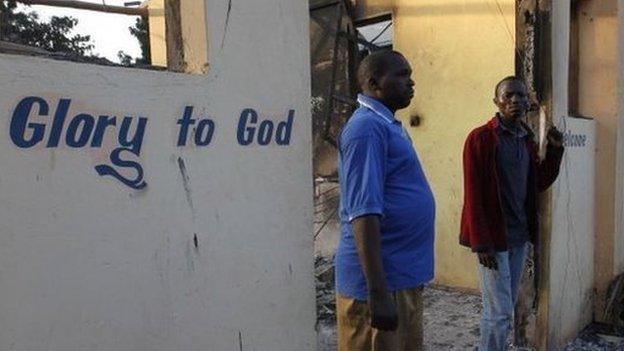

The biggest blow came just the other day, further up the coast from Mombasa, when more than 60 people were shot dead, not far from another tourist town called Lamu.

There is still confusion about exactly who carried out those attacks, and why.

During the attacks in Mpeketoni - up the coast from Mombasa - non-Muslims were not targeted

Hotels, restaurants and the police station were attacked

But there is a growing sense that all of Kenya's most pressing security concerns have somehow been rolled up into one giant crisis.

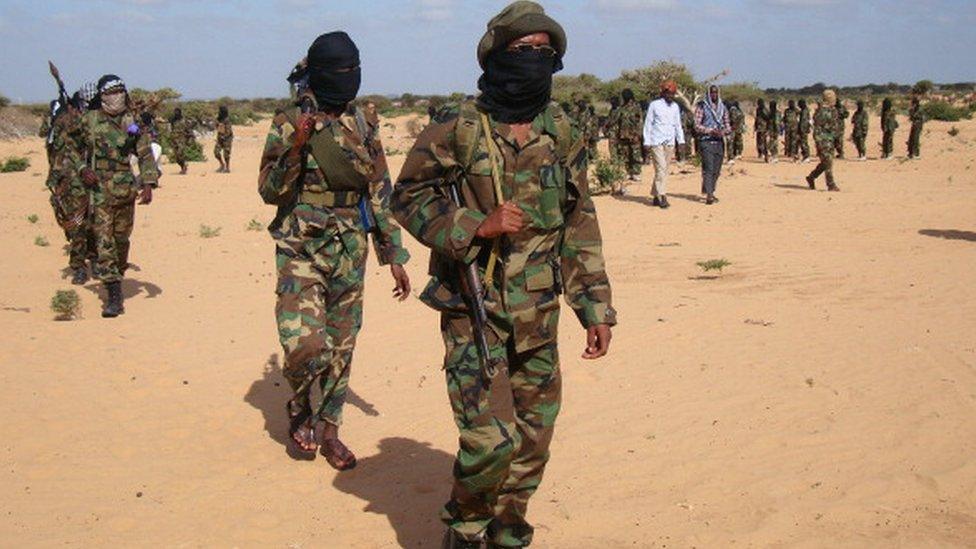

Somalia's Islamist militant group al-Shabab immediately claimed responsibility for the bloodshed near Lamu.

As with last year's attack on Nairobi's Westgate shopping mall, al-Shabab said they were simply retaliating against Kenya for sending its troops to fight them in Somalia.

Al-Shabab remains a potent threat in East Africa

But then Kenya's President, Uhuru Kenyatta, went on national television with a very different theory.

Al-Shabab, he said, had nothing to do with the latest attacks.

Instead, this was the work of unnamed locals - who were stoking political and ethnic tensions.

He offered no details, but went on to warn his political opponents not to divide the country, or indulge in hate speech.

If it was supposed to be a statesmanlike call for unity, it seems to have backfired badly, infuriating many in an already polarised nation.

Vulnerable and resentful

Soon afterwards, I was sitting in Mombasa having coffee with a local human rights activist - Khelef Khalifa - when his phone rang.

He shook his head grimly: Eight of his colleagues had just been tear-gassed, beaten and arrested for staging a tiny, peaceful rally.

Later the same day, I went to see the local Senator Hassan Omar - from the opposition alliance.

The Kenyan authorities have a fractious relationship with the more radical mosques in Mombasa

He got a phone call too. This one telling him he was being investigated by the police for alleged hate speech.

"It's madness," he said.

He accused the president of packing the state security services with members of his own Kikuyu ethnic group.

"This country is being Balkanised," he fumed.

The coast does feel particularly vulnerable - local communities resentful about more recent arrivals from inland; a broader sense that Muslims here are being marginalised; and real fears about the radicalisation of youths - and the murder, quite possibly by police hit squads, of several outspoken Muslim clerics.

Yawning judges

It was late afternoon by the time the judge arrived, sat down in court, and began to yawn rather extravagantly.

We were on the northern outskirts of Mombasa, a few hundred metres from some of the finest beach hotels.

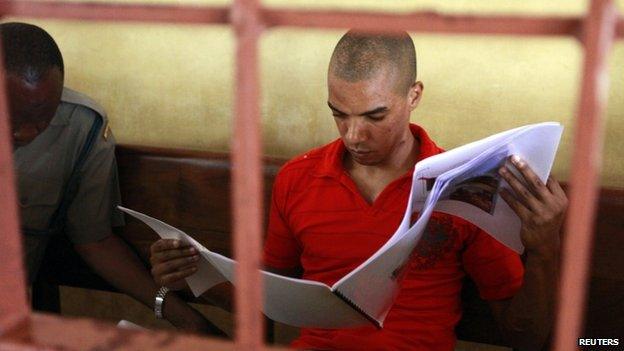

On trial, sitting under guard in a steel cage, was Jermaine Grant.

Jermaine Grant, arrested in December 2011, is alleged to have had bomb-making ingredients at his home

He is a British man, arrested more than two years ago, and accused of plotting to bomb local hotels with an accomplice, Samantha Lewthwaite - dubbed the "white widow".

She was married to one of the London 7/7 bombers, and is now on the run - perhaps in Somalia.

Mr Grant said nothing in court, as a British detective described the bomb-making equipment and coded text messages the police say they found at his flat in Mombasa.

Four ceiling fans whisked the humid air. The judge yawned again.

It is tempting to see this long-winded trial as, at best, a minor distraction on a continent wrestling - from Nigeria to Mali to Somalia and beyond - with rising extremism.

But for Kenya, as for Jermaine Grant, there is a lot at stake: Justice; the strength and independence of a nation's institutions; the rule of law.

- Published17 June 2014

- Published22 December 2017

- Published16 June 2014

- Published19 September 2012