World War One: Kenya's forgotten heroes

- Published

The BBC's Emmanuel Igunza examines the role played by Kenyan soldiers in World War One

Relatives of Kenyans who fought on the British side during World War One feel they have been forgotten. The BBC's Emmanuel Igunza visited the battlefield town of Taveta, 100 years after the war began.

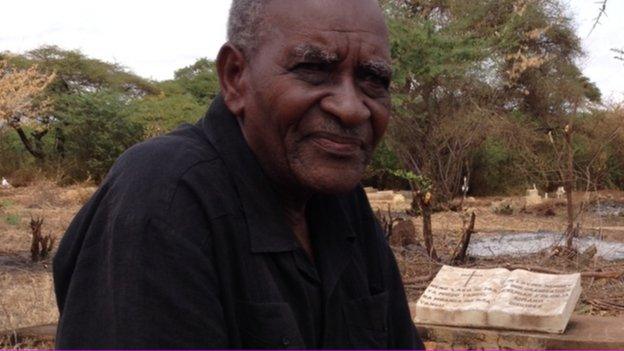

Othiniel Mnene walks slowly towards a grave at one corner of a cemetery that is used by the community here. He criss-crosses a beaten path and then sits down, pointing out a grave.

"That is my grandfather's grave. He was never the same after coming back from the war," he tells me.

"He kept asking why Africans had been involved in this war that was never theirs."

Mr Mnene's grandfather, Jeremiah Folonja, was a British spy in the town of Taveta, but he was a group of Kenyans who were captured by German forces and jailed in neighbouring Tanganyika, now Tanzania, but then a German colony.

Othiniel Mnene says his grandfather lamented being involved in a war "that was never theirs"

.jpg)

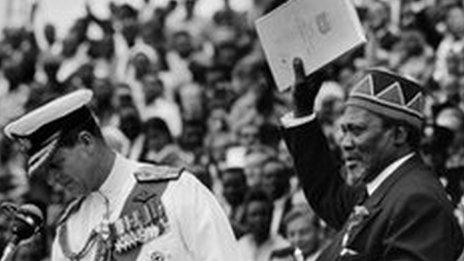

James Wilson is campaigning for greater recognition of African efforts in WW1

A memorial to honour Indian soldiers has been put up in Taveta

"Right here in Taveta, there are graves for Germans, British and even Indian soldiers. Where are the Africans graves? Why can't we just have a monument in a place like this for their remembrance?" he says.

At least two million Africans are believed to have been involved in the war, which was the longest in East Africa. Many were recruited as soldiers, but the majority worked as porters carrying ammunition, food and other supplies for both sides.

Land campaign

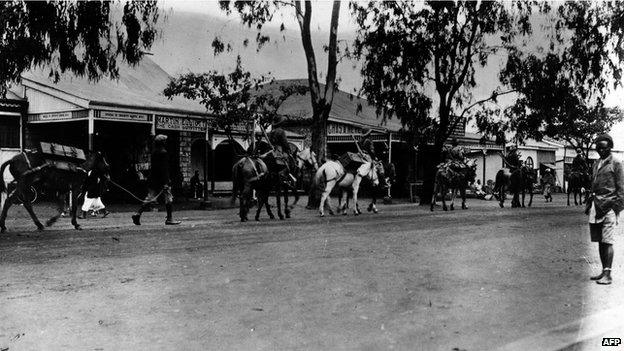

In Taveta, some 200km (125 miles) from Kenya's coastal town of Mombasa, what is a now large open field was the assembly area for such men. But the history is not well documented by the locals or the Kenyan government.

UK national James Wilson, author of Guerillas of Tsavo, says much more needs to done to preserve the memory of Africans who fought in the war.

Kenya was a British colony until 1963

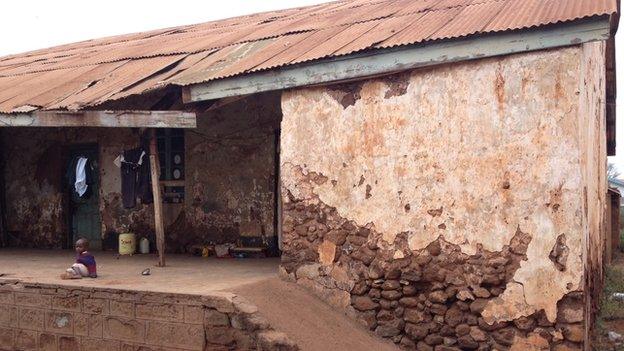

Families now live in what was a police station in Taveta during colonial rule

"Together with the local authority and friends from the UK, we are trying to put up a monument in Taveta, to remember Africans who died fighting for either side," says Mr Wilson, who has lived in Kenya since 1947.

A short distance from where we are standing at the cemetery in Taveta, there is a big dilapidated house. It was a police station 100 years ago. Now the house is being used as the living quarters for prison warders.

Soldiers from across the world

It is here, 11 days after the declaration of war in Europe, that a British government official fired a shot that killed a German soldier.

"In some ways, that shot perhaps signalled the beginning of the land campaign in East Africa," says Mr Wilson.

But the campaign had started much earlier - on 8 August 1914 the British bombed Dar es Salaam, which was then the capital of German East Africa. At least 100,000 men died in East Africa due to the war.

.jpg)

One of the major battlegrounds on Kenyan soil was the Salaita Hill in Taveta. British and Commonwealth forces tried to take the fortified hill three times, but failed.

"This was a key area. It was like the cork on the wine bottle. For the British to taste the wine, in German East Africa, they had to take Salaita Hill," Mr Wilson says.

"The fighting here was more skirmishes than battles like what were happening in Europe. The Germans mainly wanted to disrupt the infrastructure in British East Africa; in Kenya, especially the railway," he adds.

The hill still has reinforcements, trenches and embankments put up by the German forces.

While the history is not well documented by the locals, the curious names of the places echo the past - there is Salaita (derived from slaughter) Hill, nestling between Mt Kilimanjaro and the Pare Mountains. Then there is Maktau (from mark time), which hints at military drills, and Mwashoti (corruption of more shots).

Recent finds within the large expanse of short shrubs and acacia, including military hardware, have added to the fascination of the place.

.jpg)

Artefacts found at battle sites are now on display in a hotel

Among the discovered items are munitions with the date of manufacture listed as 1914, heavy-duty beer and juice bottles, British army uniforms, buttons and spent cartridges - all estimated to be 100 years old.

"So little is known about the war here in Kenya. Yet, it was the longest, continuing even after Armistice in Europe," Mr Wilson says.

The German army continued to make advances after the peace deal was signed in France - German commander Lt-Col Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck only received a telegram with news of the German defeat on 14 November 1918 and took another nine days to march his troops to meet British troops and formally surrender himself.

Discover more about the international soldiers who fought in the war and the World War One Centenary.

- Published25 November 2022

- Published10 August 2014

- Published31 July 2014

- Published29 July 2014