The 'lost' poetry of World War One

- Published

Siegfried Sassoon is one of the defining war poets of World War I, but earlier voices have been lost

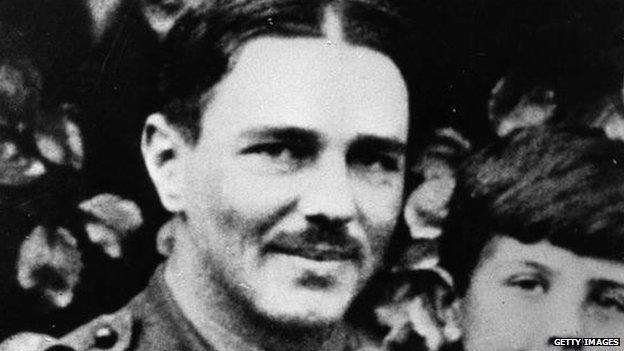

The centenary of World War One means the work of the British war poets has been much quoted of late. But the reputation of writers critical of the war, such as Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen, grew mainly after 1918.

In the early months of war newspapers printed stirringly patriotic verse on a daily basis. That work has almost disappeared from view - but is it entirely worthless?

Tim Kendall sifted through large amounts of World War I poetry to compile his new anthology, published to mark this year's centenary.

As an academic at the University of Exeter, he's a leading specialist in the verse of 1914-18 - but some of the material was unknown even to him.

"I was keen to take the collection beyond the obvious. So I looked quite hard at poetry printed in British newspapers in the first weeks of war.

"It tends to be the same few patriotic ideas recycled so I wasn't surprised very often. But that doesn't mean the poems aren't worth reading.

"You learn a lot about what Britain was thinking and fearing."

'Dominant mind-set'

A century ago it was still common for magazines and newspapers to publish poems inspired by great public occasions.

Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914. The very next day the Times carried the poem The Vigil by Sir Henry Newbolt:

England: where the sacred flame

Burns before the inmost shrine,

Where the lips that love thy name

Consecrate their hopes and thine,

Where the banners of thy dead

Weave their shadows overhead,

Watch beside thine arms to-night,

Pray that God defend the Right.

The poems were written within days or, in some cases, hours of the outbreak of war.

Few suit today's tastes, but Professor Kendall says the speed with which they emerged makes them a good indication of the dominant mind-set in 1914, so different from what came later.

Many of the poems invoke religious belief. "It's one of the big differences compared to today. I would say at least 40 percent of the poems in the papers mention God."

Kendall says there was a certain disgust that Kaiser Wilhelm was claiming early military success for the Germans as due to divine intervention. Britain's poets decided to strike back.

"But of course all newspapers have an editorial agenda. Only the most radical would have expressed doubts about the war so early on.

"To an extent many of the poets are saying what they think will get them into print and earn a fee. You could call some of it propaganda. Pretty much the same thing was happening in Germany.

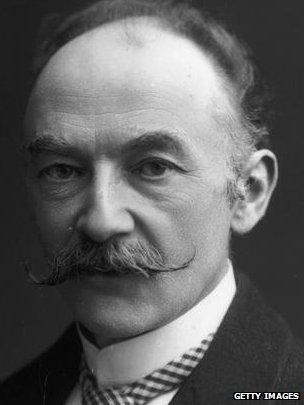

Thomas Hardy kept his doubts about the war to himself and stuck to patriotic poetry

"But at the same time the poets needed to express opinions to resonate with the public. If some of the poems now appear jingoistic, that probably echoes how many people saw the world a century ago."

Kendall points to the poem Britannia as an example of what appeared in the first days of World War I.

The author was Henry De Vere Stacpoole, known best for his novel The Blue Lagoon. It appeared in the Daily Express on 7 August 1914:

Men deemed her changed, and lo!

At word of war unveiled,

She stands, as long ago,

She stood when Nelson sailed.

The sea wind in her hair,

The salt upon her lips,

Upon the Forelands fair

She guards the English ships.

"Whatever you think of Britannia as poetry," Kendall says, "it tells us something about history. Large numbers of people in Britain thought the nation had just set out on what was basically a naval war.

"It's not the only poem where you find stirring references to the Armada and Trafalgar or to Sir Francis Drake.

"Today our view of the war is entirely different: it's mainly the mud of Flanders and the Western Front.

"That has become a deep-rooted part of British culture and it's partly down to the impact the poets of the trenches had after the war - Sassoon and Owen and Graves and the rest. There were no seaborne equivalents."

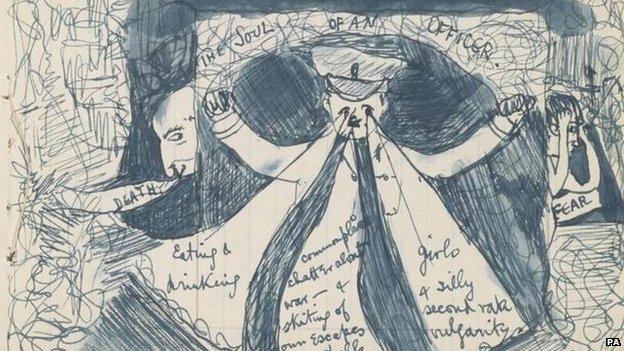

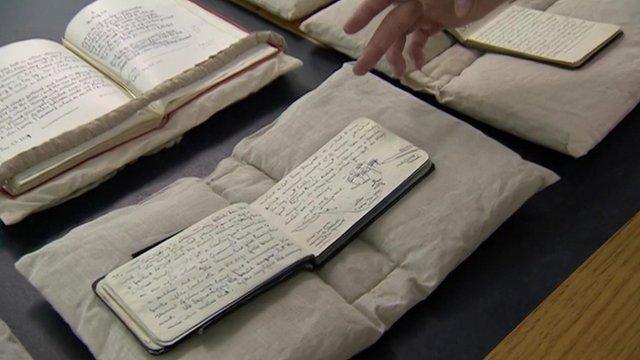

War poets such as Siegfried Sassoon, and their reflections on life in the trenches - as documented in Sassoon's diaries here - dominate our impressions of World War I

The 1914 book, Songs and Sonnets for England in War Time, collected many of the poems which had just appeared in newspapers.

It contains two pieces by poets still widely read today, both originally published in the Times in September that year.

Kendall says Thomas Hardy's Song of the Soldiers (also known as Men Who March Away) in many ways shares the patriotism of the poetry that was printed before it.

"We know that Hardy privately had many doubts about the war: he admitted that he couldn't write patriotic poetry very well because he always saw the other side too much. But he felt unable to express his doubts in public."

Rudyard Kipling's For All We Have and Are was published on 2 September:

For all we have and are,

For all our children's fate,

Stand up and meet the war,

The Hun is at the gate!

Kendall argues that Wilfred Owen - our best-known war poet - should not simply be viewed as "anti-war"

But with these few exceptions the patriotic poetry printed in newspapers during World War I, once read by millions, is now virtually forgotten.

A century on the most admired poet of the war is Wilfred Owen, who only had five poems published before his death in November 1918 at the age of 25.

His story has come to chime with the sense of waste and sadness with which people now regard the war in which men fought.

But Kendall says to describe either Owen or Sassoon as anti-war is too simplistic.

"Both men won the Military Cross. What they detested was the attitude of the politicians and the public who had no idea what life was like for those doing the fighting."

Nor should we dismiss all the poetry which appeared in print in 1914 as jingoistic rubbish.

"Sassoon and Owen and others came to question the war they fought in - it's partly why we now admire them. Perhaps we feel they're more like us than the Henry Newbolts of this world.

"But we should resist the temptation to think we always know better than everyone in 1914.

"It's easy to mock them in retrospect. We have the enormous advantage of knowing the horror that lay in wait in the four years ahead."

- Published5 August 2014

- Published1 August 2014

- Published29 July 2014

- Published24 October 2013