Ebola drains already weak West African health systems

- Published

Abba Abashi, Liberian-Nigerian student: "My mum caught me crying"

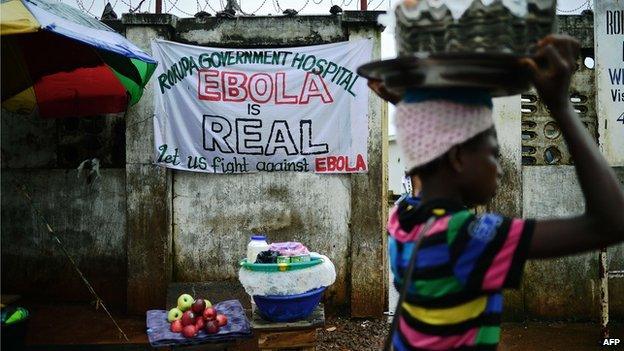

The deadly Ebola virus ravaging Sierra Leone and Liberia has pushed already weak healthcare systems into intensive care.

While global efforts have been focused on Ebola, many people have failed to receive treatment for other diseases such as malaria and measles, and this has led to even more deaths, experts say.

"It's a vicious cycle," Sierra Leonean risk analyst Omaru Sisay told the BBC.

"Because of Ebola, cases of people not being treated for malaria, cholera and measles have increased significantly," he says.

Painting a similar picture about Liberia, the UN children's agency Unicef says Ebola has severely disrupted health services for children, caused schools to close and left thousands of children without a parent.

"Children are dying from measles and other vaccine-preventable diseases and pregnant women have fewer places to deliver their babies safely," it said in a statement.

Sierra Leone's health services were neglected because of conflict

Liberia has been badly affected by the outbreak - here a mother and daughter lie down near a treatment centre

Liberia risks an outbreak of water-borne diseases

The BBC's Jonathan Paye-Layleh in the Liberian capital, Monrovia, says that while statistics are not available, suspicion exists that some of the deaths attributed to Ebola have been caused by cholera, malaria, typhoid and other illnesses, as people either did not go to hospitals or were turned away by medical workers who feared that they carried the deadly virus.

He says with the rainy season under way, the government has in recent weeks taken steps to prevent a cholera outbreak by chlorinating wells in Monrovia.

Unicef estimates that 8.5 million children and young people under the age of 20 live in areas affected by Ebola in Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea. Of these, 2.5 million are under the age of five.

Skills shortage:

Liberia with a 4.2m population: 51 doctors; 978 nurses and midwives; 269 pharmacists

Sierra Leone with a 6m population: 136 doctors; 1,017 nurses and midwives; 114 pharmacists

Source: Afri-Dev.Info

It is a cruel twist that Liberia and Sierra Leone have been worst affected by the deadliest ever Ebola outbreak, as the two countries were still recovering from brutal civil wars that decimated their infrastructure in the 1990s when the disease hit.

The virus spread from Guinea, which borders both nations. It has been far more effective in containing the outbreak because it has more resources and a "more resilient" health system, Mr Sisay says.

'Black bag doctors'

Similarly, Nigeria, one of Africa's wealthiest states, has contained the virus after it was brought to the country by a Liberian government worker travelling on a commercial airline.

Nigeria has been able to contain the outbreak

In contrast, Liberia and Sierra Leone are poor, with almost non-existent health systems.

Liberia has 51 doctors to serve the country's 4.2 million people (an average of 0.1 doctor per 10,000 people) and 136 for Sierra Leone's population of six million (an average of 0.2 per 10,000), according to data compiled by the Afri-Dev.Info, external health and social development agency.

Tune in to the BBC World Service at 19:00 GMT on Friday 26 September to listen to The Africa Debate: Do failed health systems in Africa make global epidemics inevitable? The programme will also be available to listen to online or as a download.

To take part on Twitter - use the hashtag #BBCAfricaDebate - Facebook or Google+

Against this backdrop, many Liberians rely on what are locally known as "black bag doctors" who go from village to village to treat people, often with fake or outdated drugs, our correspondent says.

When people do not have money to pay the "black bag doctors", he adds, they give them some of their best livestock - chickens or goats.

In Sierra Leone, state-employed health workers do private home visits, Mr Sisay says.

"They work on the side and treat patients at home. A maternity nurse may treat somebody who has high blood pressure; a dispenser somebody who has a respiratory illness."

And when Ebola spread across the two nations, people refused to go to hospitals because they saw them "as the most dangerous place to be", Mr Sisay says.

He was referring to the fact that hospitals were seen as the source of the disease. It has claimed the lives of many health workers - 61 in Sierra Leone, including its only virologist, Dr Umar Khan.

Ebola voices: Lionel Fredericks in Liberia

I'm a medical student and I should have sat my exams by now but the Liberian government closed all schools in August.

We now live in fear and it is so intense that even having a small fever makes you very afraid.

I tried to avoid mosquito bites as I don't want even getting the slightest illness.

Many people also did not bother to go to hospital, as there is no cure for Ebola - although supportive care such as rehydrating patients who have diarrhoea and vomiting can help recovery.

The deaths of top medics has raised concerns that healthcare could get even worse if the heavily donor-dependent Liberian and Sierra Leonean governments fail to replace them.

"The Ebola crisis demonstrates Africa's health workforce shortages will not disappear without improved long-term multi-sectoral co-ordination, planning and investment across education, labour, human resources and health sectors," says Afri-Dev.Info.

Many African governments are accused of neglecting basic standards of hygiene

Mr Sisay says the fact that many African leaders go abroad to receive treatment shows they do not have confidence in the health systems of their own countries.

Commenting on why they do not face a public backlash from voters, he replies: "Why do people accept gutters overflowing with rubbish? Why do people accept officials taking kickbacks? In Africa, people have become accustomed to mediocrity because they have been governed badly for many years."

'Rock-bottom'

Dr Johanna Hanefeld of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine says donors tend to focus on "disease-specific funding" - for instance, by spending on medicines for a million children at risk of malaria, as this makes it easier to justify expenditure to their domestic constituencies.

However, this is changing as donors realise the importance of funding "hardware" like hospitals and equipment - an initiative that could gain momentum following US President Barack Obama's announcement last week of help to build hospitals and train health workers, Dr Hanefeld notes.

Ultimately though, health services are most effective in countries with a large tax base, which is not the case in Liberia or Sierra Leone, or where there is a political will to invest, like Cuba, Costa Rica and Sri Lanka, she adds.

Expressing a similar view, Mr Sisay says Liberia and Sierra Leone have hit "rock-bottom" since the Ebola outbreak - and a concerted effort will have to be made by their governments and foreign donors to ensure they are better-placed to cope with any future crisis.

Ebola virus disease (EVD)

Symptoms include high fever, bleeding and central nervous system damage

Spread by body fluids, such as blood and saliva

Fatality rate can reach 90% - but current outbreak has mortality rate of about 70%

Incubation period is two to 21 days

There is no proven vaccine or cure

Supportive care such as rehydrating patients who have diarrhoea and vomiting can help recovery

Fruit bats, a delicacy for some West Africans, are considered to be virus's natural host